Covered in Ink, Cross-sections of Trees Make Gorgeous Prints

Connecticut-based artist Bryan Nash Gill uses ink to draw out the growth rings of a variety of tree species

When I phoned Bryan Nash Gill last Thursday morning, he was on his way back from a boneyard. The New Hartford, Connecticut-based artist uses the term not in its traditional sense, but instead to describe a good spot for finding downed trees.

“I have a lot of boneyards in Connecticut,” says Gill. “Especially with these big storms that we have had recently. Right now, in the state, the power companies are cutting trees back eight feet from any power line. There is wood everywhere.”

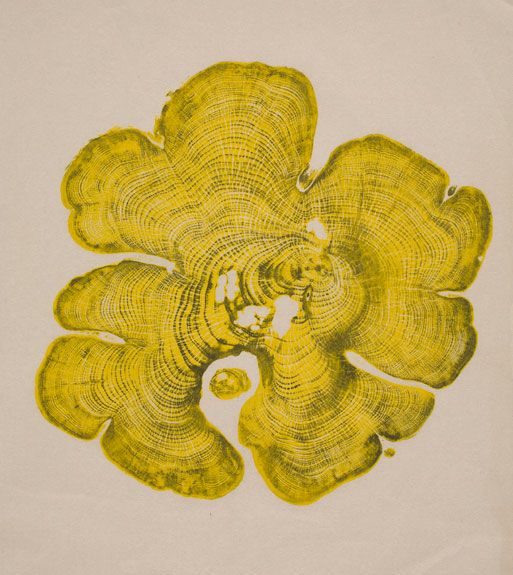

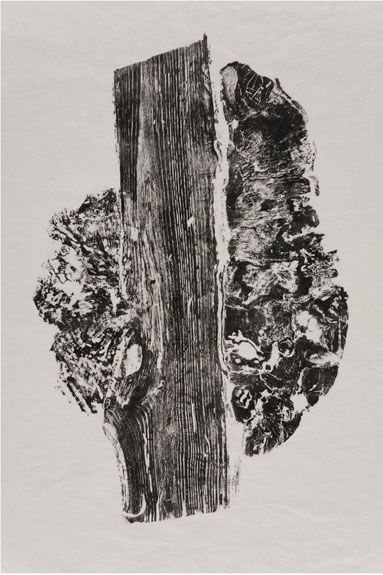

Gill collects dead and damaged limbs from a variety of indigenous trees—ash, oak, locust, spruce, willow, pine and maple, among others. “When I go to these boneyards, I am searching for oddities,” he says, explaining that the trees with funky growth patterns make the most compelling prints.

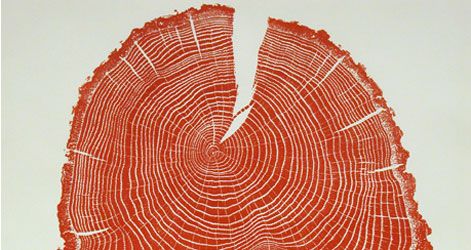

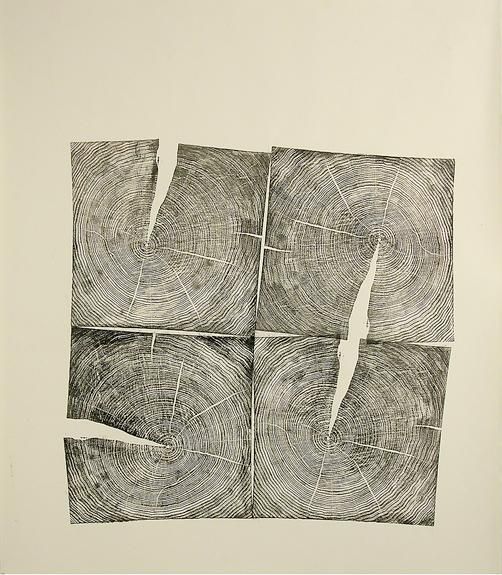

For almost a decade, Gill has been hauling wood back to his studio. He saws a block from each branch and sands one end until its smooth. Gill chars that end, so that the soft spring growth burns away, leaving behind the tree’s distinct rings of hard, summer growth. He seals the wood and covers it with ink. Then, he lays a thin sheet of Japanese rice paper on the cross-section, rubs it with his hand and peels the paper back to reveal a relief print of the tree’s growth rings.

Gill recalls the very first print he made of an ash tree in 2004. “When I pulled that print off, that transfer from wood to ink to paper,” he says, “I couldn’t believe how gorgeous it was.” Years later, the artist is still splitting open tree limbs to see what beautiful patterns they hold within.

In 2012, Gill released Woodcut, a collection of his prints—named one of the year’s best books by the New York Times Magazine. His cross-sections of trees, with their concentric rings, are hypnotizing. Nature writer Verlyn Klinkenborg, in the book’s foreward, writes, “In each Gill print of a natural tree-face—the surface sanded and the grain raised—you can see a tendency toward abstraction, the emerging of pure pattern. In their almost natural, black-and-white state, you can read these prints as Rorschach blots or as topographic reliefs of very steep terrain.”

The artist has attempted to draw the growth rings of trees. “You can’t do it better than nature,” he says.

Gill grew up on the same farm in northwest Connecticut where he now lives and works. The outdoors, he says, have always been his playground. “My brother and I constructed forts and lean-to villages and rerouted streams in order to make waterfalls and homes for the crawfish we caught,” Gill writes in the book. After graduating from high school, the creative spirit studied fine arts at Tulane University in New Orleans. He then went on to earn a master of fine arts degree from the California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts) in Oakland. “In graduate school, I concluded that art is (or should be) an experience that brings you closer to understanding yourself in relation to your surroundings,” he writes.

In 1998, Gill built a studio adjoining his house. Initially, he experimented by making prints of the end grains of the lumber he was using—four-by-fours, two-by-fours and eight-by-eights. But, soon enough, he turned to wood in its more natural state, intrigued by the wonky edges of the slices he’d saw from tree trunks.

“I am kind of like a scientist, or a dendrologist, looking at the inside of a tree that no one has seen,” says Gill. His eye is drawn to irregularities, such as holes bored by insects, bark that gets absorbed into the core of the tree and odd outgrowths, called burls, formed by viruses. ”It is a discovery process,” he says.

In earlier days, in much the same way, Gill would study the growth rings in carrots he’d pluck and slice from his parents’ garden on the property. “I am just fascinated with how things grow,” he says. “It is like being a kid again.”

Gill has made prints of tree boles measuring from an inch to five feet in diameter. According to the artist, it is actually easier to determine a tree’s age from his prints than from trying to count the individual growth lines on the wood itself.

“Some of the simplest things are the most complex things,” says Gill. “I like that binary. This is very simple, but it has taken me 30 years to get here.”

More than 30 original prints by Gill will be on display in “Woodcut,” an exhibition at the Chicago Botanic Garden from January 19 to April 14, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)