Curiosity Found Evidence of An Ancient Freshwater Lake on Mars

Drilling into Martian rock revealed that it formed at the bottom of a calm lake that may have had the right conditions for sustaining life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/5f/c35fac5d-8694-483b-ad53-37429cc53853/mars_lake.jpg)

Shortly after NASA's Curiosity rover landed on Mars in August 2012, the scientists guiding the device decided to make a temporary detour before heading to the mission's ultimate destination, Mount Sharp. Last spring, they guided the six-wheeled machine towards Yellowknife Bay, a slight depression with intriguingly lighter-toned sedimentary rocks, and drilled its first two holes in Martian rock in order to collect samples.

Afterward, as Curiosity drove away from Yellowknife Bay, onboard equipment ground the rock samples to a fine dust and chemically analyzed their content in extreme detail to learn as much as possible about the site. Today, the results of that analysis were finally published in a series of articles in Science, and it's safe to say that the scientists probably don't regret making that brief detour. Yellowknife Bay, they discovered, was likely once home to a calm freshwater lake that lasted for tens of thousands of years, and theoretically had all the right ingredients to sustain microbial life.

A panorama of the Yellowknife Bay area, with different rock areas named and dots showing locations of rock analysis. Click to enlarge.

"This is a huge positive step for the exploration of Mars," said Sanjeev Gupta, an Earth scientist at Imperial College London and a member of the Curiosity team, in a press statement on the discovery. "It is exciting to think that billions of years ago, ancient microbial life may have existed in the lake's calm waters, converting a rich array of elements into energy."

Previously, Curiosity found ancient evidence of flowing water and an unusual type of rock that likely formed near water, but this is the strongest evidence so far that Mars may have once sustained life. The chemical analysis of the two rocks (named "John Klein" and "Cumberland") showed that they were mudstones, a type of fine-grained sedimentary rock that generally forms at the bottom of a calm body of water, as small sediment particles gradually settle on one another and are eventually cemented together.

Isotope analysis indicated that these rocks formed sometime between 4.5 and 3.6 billion years ago, either during Mars' Noachian period (in which the planet was likely much warmer, had a thicker atmosphere and may have had abundant surface water) or early on in its Hesperian period (in which it shifted to the dry, colder planet we see currently).

Additionally, a number of key elements for the establishment of life on Earth—including carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, sulfur, nitrogen and phosphorous—were found in detectable quantities in the rocks, and chemical analysis indicated that the water was likely of a relatively neutral pH and low in salt content. All of these discoveries increase the chance that the ancient lake could have served as a habitat for living organisms.

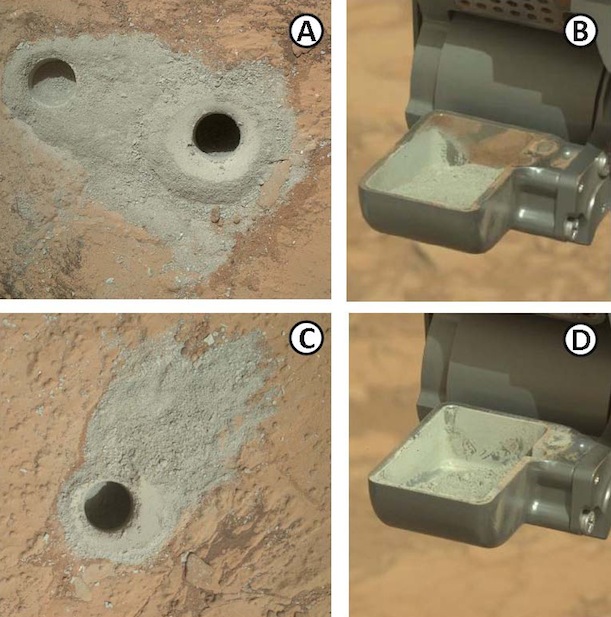

A shallow test drill hole next to a complete drill hole into the rock "John Klein" (A) and a drill hole into "Cumberland" (C), with Curiosity's scoop filled with each of the respective samples (B and D)

The scientists hypothesize that the microorganisms most likely to live in this environment would have been chemolithoautotrophs, a type of microbe that derives energy by breaking down rocks and incorporates carbon dioxide from the air. On Earth, these types of organisms are most often found near hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, where they thrive off chemicals emitted into the water.

Obviously, this isn't direct proof of life, but rather circumstantial evidence that it may have once existed. Still, it's yet another vindication of Curiosity's mission, which is to determine the planet's habitability. Over the coming months and years, the scientists guiding the rover plan to keep sampling sedimentary rocks on the planet's surface, hoping to find further evidence of potentially-habitable ancient environments and perhaps even direct evidence of now-extinct living organisms.

For more, head over to NASA's webcast of the press conference announcing the findings, which occurred today at noon EST.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)