The Strange Reappearance of the Once-Vanished Green Sea Turtle

It’s a conservation biology riddle wrapped in a mystery inside a hard shell

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/56/8e5676cf-412a-402c-9ad0-eb8b74db51b5/istock_87318315_large-wr.jpg)

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

The morning was dusky, sunrise nearly an hour off, when Frank Burchall pulled out of his driveway on Bermuda’s east end, his granddaughter Mimi beside him, and headed for work in the languid seaside port of St. George’s. Burchall’s route took him along Barry Road, a single-lane coastal track that wends between pastel houses on one side and the cerulean sea on the other.* Daylight began to bleed into the dim world. And then, in his headlights, Burchall saw the wanderer.

His first thought was that the diminutive creature waddling across the road on August 16, 2015, was a freshwater turtle—maybe a terrapin or a slider. But when he picked up the reptile, he realized it was something different. Something with flippers. Burchall put the errant sea turtle—which Mimi named, predictably, Mimi—into a pot and drove south to the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum and Zoo, where the captive was installed in a quarantined tank and entrusted to an aquarist named Ryan Tacklin. The caretaker inspected the turtle with growing excitement: its blue-gray carapace was just a thumb’s-length wide, and a faint, belly-button-like scar, where the creature had recently been connected to its egg, creased its plastron. “It was obvious that it had hatched within the last few hours,” Tacklin recalls.

Tacklin texted pictures to colleagues, who confirmed his suspicions. The animal was a newly hatched green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas, a species that had not been born on a Bermuda beach in nearly a century.

Although green turtles roam temperate and tropical oceans around the world, the Caribbean (and neighboring islands such as Bermuda) was once a special stronghold: explorers claimed the sea was so thick with turtles that European sailing ships could navigate by the animals’ plosive exhalations. After the English aristocracy developed a taste for turtle soup in the 19th century, however, populations of green turtles—so named for the hue of their fat—nosedived. By 1878, soup manufacturers were shipping more than 15,000 live turtles across the Atlantic each year to be stuffed into cans.

As the appetite for turtle meat spread to the United States, the pig-sized reptiles began vanishing from subtropical and tropical Atlantic beaches—including Bermuda’s. The lush seagrass pastures off the country’s coast remain important feeding grounds for juvenile green turtles, herbivores that saw off vegetation with their serrated, toothless jaws. But while subadults from as far as the Mediterranean partake in Bermuda’s submarine buffet, the island hasn’t hosted a nesting population since the 1930s. “We’d all been hoping that someday this would happen again,” Tacklin says. “But none of us expected it at all.”

Burchall’s discovery thrilled the entire country, yet it baffled scientists—where had the cryptic hatchling come from? To many, the turtle’s presence raised a compelling question: had a seemingly futile conservation effort, abandoned amidst tragedy almost 40 years ago, actually succeeded?

**********

Although Bermuda hasn’t had nesting green turtles for decades, it wasn’t for lack of trying. And trying. The nation’s turtle recovery efforts date at least to 1963, when scientist David Wingate, Bermuda’s first conservation officer, launched an audacious scheme to restore a crescent of rock and jungle called Nonsuch Island.

Nonsuch, about the size of nine city blocks, lies in the northeastern corner of the Bermuda archipelago. Wingate, who’d studied zoology at Cornell University in New York State before returning to his native Bermuda, hoped to transform the island into a living museum—a re-creation of what the outpost probably looked like before British settlers devoured seabirds, introduced rats, and generally bollixed up the ecosystem. Over the decades, Wingate vanquished invasive rodents, planted native vegetation, and reintroduced species, from the yellow-crowned night heron to a resplendent snail called the West Indian top shell.

But for Wingate and his fellow Bermudans, the Nonsuch Island Living Museum remained incomplete without one of its most charismatic ex-residents: the green sea turtle.

Fortunately, Wingate was not the only biologist then trying to bring back vanished marine reptiles. In 1959, another legendary scientist, Archie Carr, had begun Operation Green Turtle, his own ambitious restoration project for the Caribbean Conservation Corporation (now known as Sea Turtle Conservancy). Under the plan’s auspices, Carr collected 130,000 green hatchlings at Tortuguero, a turtle-rich stretch of Costa Rican shoreline, over 10 years, and relocated the younglings to Barbados, Honduras, Belize, Puerto Rico, and other coasts that had been ransacked for their turtles. The US Navy assisted Carr’s effort, donating several amphibious planes to airlift the animals. With any luck, Carr thought, the turtles would imprint on their new homes and, years hence, return to their release sites to lay eggs.

Several years into the project, by fortuitous coincidence, Wingate wrote Carr a letter soliciting suggestions for repatriating turtles to his living museum. When Carr described Operation Green Turtle to his Bermudan colleague, Wingate realized he’d found the solution to repopulating Nonsuch Island’s shores. By that point, Carr had come to believe that hatchlings were too old to imprint upon unfamiliar beaches, so he decided to relocate eggs instead of newborns. The two scientists traveled repeatedly to Tortuguero, crouching behind mama turtles and gingerly transferring clutches of freshly laid spheres into styrofoam boxes. After the navy requisitioned its military airplanes for the Vietnam War in 1968, collecting trips became perilous. On one occasion, Wingate’s tiny chartered plane was so crammed with eggs that his wife, Anita, perched on his lap. “I remember the pilot doing the sign of the cross as he set off down the grass runway with the rainforest looming ahead of us,” Wingate recalls.

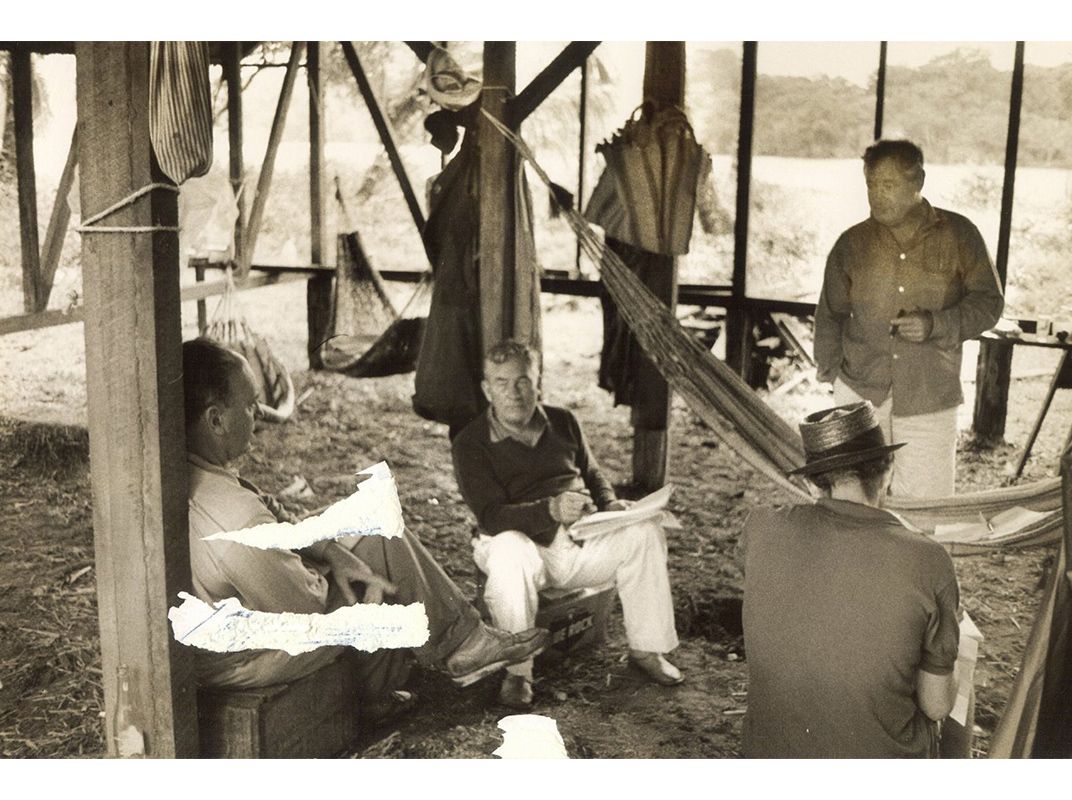

Wingate survived that journey, and many more. He spent years digging nests and reburying the eggs on Nonsuch Island, as well as on a private strip of beach owned by Henry Clay Frick II, the philanthropic grandson of the famed industrialist of the same name. Carr, the Wingates, and Frick’s daughter, Jane, would camp on the beach for weeks, awaiting each hatch. When the newborns emerged, one of the Wingates’ two young daughters sometimes swam out to sea alongside the babies, defending them from fish and gulls. Altogether, the project produced over 16,000 hatchlings. It was a labor of reptilian love.

But tragedy interrupted Wingate’s efforts. In 1973, Anita died in a house fire—“shattering my life,” as Wingate puts it. The biologist, stricken with grief, was tasked with raising his daughters alone. The same year, the government of Costa Rica revoked his permit to collect eggs, and the relocations ceased. Calamity struck several years later, when Jane Frick committed suicide. By the time Carr died in 1987, not a single plundered Caribbean beach had regained its green turtles. And so Operation Green Turtle ended, another doomed conservation scheme on a planet gouged by extinction, another scar on a wounded world.

**********

On the morning of Frank Burchall’s find, David Wingate, now 80 years old, was birdwatching near St. George’s, a 10-minute drive from where the hatchling had crossed Barry Road. A local conservationist alerted him to the discovery at around 10:00 a.m., sending Wingate racing for Buildings Bay beach, where Ryan Tacklin and other aquarium staff had rushed to look for additional hatchlings. Slow-motion chaos greeted the retired scientist: more newborns had indeed emerged the previous night, but the beckoning lights of civilization had lured them astray. Around a dozen had taken shelter in the shade of nearby shrubs. A gaggle of residents, drawn by the commotion, scoured the vegetation for wayward turtles.

“People were crawling around on their knees in the weeds,” remembers Anne Meylan, a Florida-based sea turtle biologist who happened to be conducting research in Bermuda that week. “It elicited such a sense of wonder.” The community was entranced.

The scientists released the hatchlings into the ocean, though three didn’t survive the ordeal. Tacklin and others camped on the beach that night and guided two more stragglers to the sea; the local electric company agreed to switch off nearby streetlights. Three days later, aquarists knelt in the sand and, with their hands, dug out the waist-deep nest chamber. At the cavity’s bottom they found two more living hatchlings, four infertile eggs, and the remains of 86 hatched eggs. Altogether, nearly 100 baby greens had vanished into the sea.

The speculation began immediately: could these hatchlings be the offspring of a long-lost Operation Green Turtle transplant? Nearly four decades had passed since Wingate relocated his last clutch of turtle eggs. While most female green turtles reach sexual maturity between 25 and 35 years old, a 40-year-old first-timer wasn’t out of the question.

Meylan, however, was skeptical. She suspected the mysterious mother had come from Florida, where conservation efforts, especially the protection of prime nesting beaches, had recently produced a shelled eruption. In 2015, green turtles dug 37,341 nests in the Sunshine State—the most since record-keeping began. Perhaps a disoriented turtle from the vast Floridian armada had meandered 1,000 kilometers off course. Meylan collected the three dead hatchlings, cut slivers of tissue from their flippers and shoulders, and shipped the samples to a genetics expert at the University of Georgia. Surely the cold, hard light of DNA testing would reveal the answer.

The analysis, however, proved unenlightening. According to unpublished genetic tests, the likelihood that Bermuda’s turtle is descended from either Floridian or Costa Rican stock is less than 10 percent. Meylan’s current hypothesis is that the migrant arrived from Mexico, which also hosted a bumper turtle crop in 2015. New genetic techniques may someday provide a definitive answer, but, says Meylan, “The female turtle’s origin will have to remain a mystery for the time being.”

**********

If that non-resolution sounds anticlimactic, well, not every scientific conundrum gets solved. And in a way, the origins of the stunning nest matter less than the simple fact of its appearance. Many scientists believe that sea turtles are too faithful to their forebears’ home beaches to be effectively translocated; Meylan posits that turtles have hardwired genetic knowledge of the geomagnetic map leading them to their ancestral shores. Given the creatures’ usual precision, the fact that an errant green turtle showed up in Bermuda at all is fairly remarkable.

There’s no proof that Operation Green Turtle ever repopulated any Caribbean or neighboring beaches, and Meylan cautions against attempting more translocations without evidence. Yet at least one other effort suggests that turtle translocation is possible in some circumstances. In the 1990s, scientists managed to re-establish Kemp’s ridley sea turtles on Padre Island, Texas, to protect the dwindling species from extinction. The rigmarole of that project dwarfed even the arduousness of Operation Green Turtle: starting in 1978, biologists collected Kemp’s ridley eggs in Mexico, incubated them in controlled conditions, and let the hatchlings crawl into the Padre Island surf. After a quick romp in the waves, the babies were scooped up with a dip net and transported to Galveston, Texas, to be raised in the safety of a lab for a year before release. The elaborate procedure worked: nearly two decades after the first Kemp’s ridleys were turned loose, tagged females showed up on Padre Island to deposit the next generation. By 2012, more than 200 nests were being dug in Texas annually.

Coming years will tell whether green turtles have likewise returned to Bermuda, or whether last summer’s nest was a false promise. For now, though, the enigmatic hatchlings offer reason to believe that the disappearance of green turtles from Caribbean beaches may not be terminal.

For no one is that possibility more poignant than for Wingate, the man who strived for decades to restore his island’s native fauna, endured unimaginable personal tragedy, and lived to see a green turtle nest on Bermuda for the first time in his 80 years.

“Whether it was by translocation or not, this event has tremendous global significance,” Wingate says. “It means that it’s not a completely lost cause if you lose turtles on a nesting beach.” Though the grand ambitions of Operation Green Turtle may never be realized, spontaneous recolonization, without direct human aid, now seems conceivable. Adds Wingate, his voice quavering with emotion, “There is always hope.” For Bermuda’s most eminent conservationist, that’s legacy enough.

Read more coastal science stories at hakaimagazine.com, including: