Curly Hair Science Is Revealing How Different Locks React to Heat

A mechanical engineer tackles the understudied problem of how to style curls without frying hair

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/74/0d74090b-f489-4d71-a012-7d1d3fb7c183/istock_000058514552_medium.jpg)

Every day, countless people tackle their natural curls with a flat iron—then tackle their own frustration with hair that’s been irreparably fried in the process. Tahira Reid wants to fix that. She’s a mechanical engineer on a mission to find out exactly how much heat curly hair can sustain before damage sets in.

Reid stopped chemically relaxing her curls years ago, but she knows all about the time, money and potential long-term damage that can go along with a simple hairstyle. She describes herself as an engineer who specializes in research that solves real-people problems, so when a search for scientific data on heat treatments came up short, she decided to pursue the case.

“However a woman chooses to wear her hair is her own personal expression of beauty,” she says. “This research is not to tell women to have straight hair—it’s for women who choose to wear their hair straight but face heat damage if they do.”

In their initial literature search, Reid and her colleagues at Purdue University found plenty of word-of-mouth advice and hundreds of thousands of YouTube videos. They didn’t find much hard scientific data on which temperatures might damage curls. Even worse, traditional sources like cosmetology books were outdated, sorting hair into three catchall categories: Caucasian, Asian and African.

“The world is not those three categories,” says Reid—and neither is hair. Though people of all backgrounds can be born with tightly curled hair, the scant scientific research on how hair is affected by heat didn’t take that variety into consideration. While all hair is made of the same proteins, the geometries and textures can vary. A newer method of hair classification called Segmentation Tree Analysis has identified eight types of hair based on their curvature, from Type I (straight) to Type VIII (zigzag coils). The curlier the hair, the more likely it is to have weak cross-sectional points that make it vulnerable to breakage and heat damage.

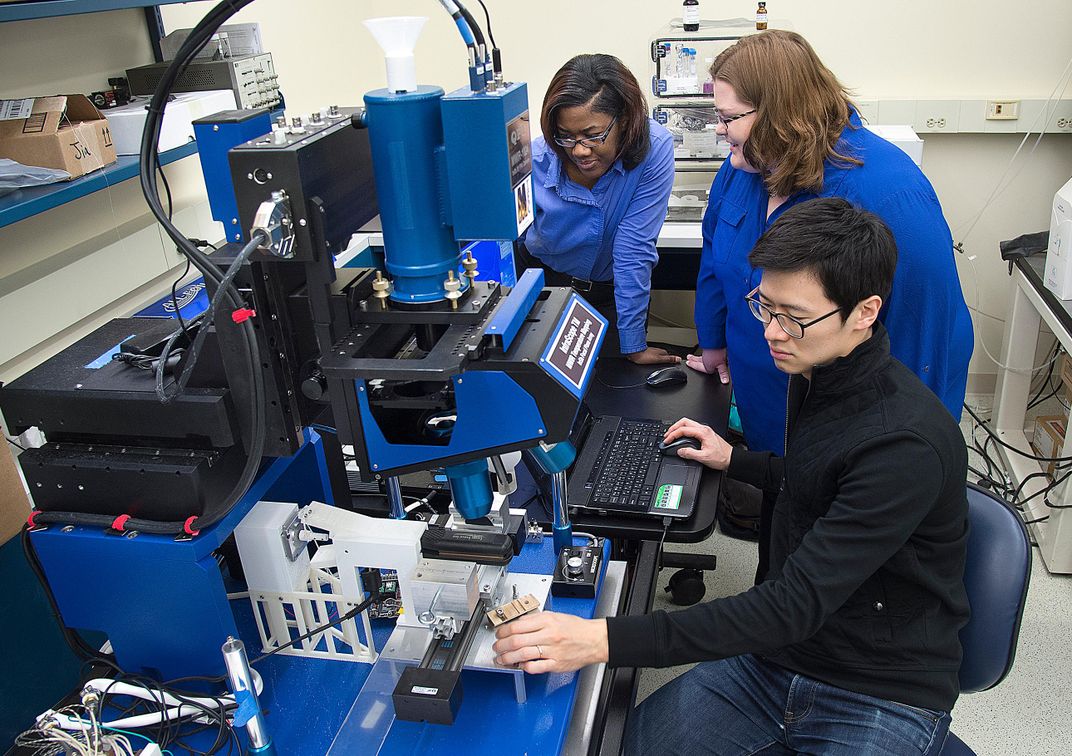

For their latest study, Reid's team used an automated flat-ironing device of their own design to test different temperature settings across all eight hair types. The team mounted each hair sample, straightened it and used an infrared microscope to study how it reacted. Reid presented their preliminary results this week to an international design engineering conference hosted by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

In upcoming work, the team expects to be able to use their new method of hair study to determine heat tolerance thresholds for each variety of curly hair—thresholds that could be used by professional and everyday stylists to help straighten hair without damaging it. Future experiments will focus on the role of humidity, curl density and more refined methods of automatic straightening.

Reid acknowledges that the subject of hair straightening has been a hot-button issue in the United States, which has a checkered past when it comes to perceptions of race and hair. Comments about naturally curly hair still accompany racial slurs, and women of color in particular have long faced social pressure to conform to white-centric beauty standards.

Some influential African-Americans, like Madame C.J. Walker and Garrett Morgan, popularized straightening techniques like the hot comb and invented chemical relaxers to change the structure of the hair shaft. While these treatments and procedures gave curly-haired women the option to wear their hair straight, they were time-consuming and damaging, and many people felt their use wasn’t optional. To this day, many styling products developed specifically for curly hair are still only available in the so-called ethnic aisle, which features hair-care products marketed directly to people of color.

In addition to helping would-be straighteners personalize their hair care, Reid hopes her work will prompt modern-day researchers to move away from such old-fashioned stereotypes about curly hair.

Why’s curly hair so complicated? Pedro Miguel Reis, a mechanical engineer at MIT who has published work on the physics of curls, chalks it up to the nature of shapes themselves. “Curls have a nonlinear geometry,” he notes, meaning they are more challenging to model mathematically. But he's quick to add that just because they’re tricky doesn’t mean they’re not worth studying.

Reid agrees. Then again, she’s made a career studying things others might overlook. In 2002, Reid received a patent for a device she developed as a student at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: a double-dutch machine she exhibited at the National Museum of American History and on the TODAY Show. Though she used to minimize the ways in which her work draws on her daily experiences, now she’s more confident. “After all,” she says, “hair is a mechanical system, too.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)