The Dangerous Work of Relocating 5,000-Pound Rhinos

The race is on to save the species: Ride along with an armed convoy deep into the Okavango Delta

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/e8/5de8656c-d806-4715-85e0-9693fd9914f8/jun2018_j05_rhinos.jpg)

As the sun drifted down on the rolling hills of South Africa’s Free State province, Manie Van Niekerk wore a mournful look. The 52-year-old farmer and rancher, whose short hair is dark on top and gray on the sides, has a sturdy, solid frame formed by decades of physical work. He looks like a man who is hard to shake. And yet, talking about his 32 rhinoceroses, which at that moment he was preparing to give away, he was visibly moved. “You fall in love with the rhino,” he told me. “You get a lot of joy looking at them. They are dinosaurs. You can look at them and imagine the world before. People think they’re clumsy, but they’re actually very graceful. Like ballerinas.”

He makes his living growing maize and potatoes on his family’s 57,000-acre farm, but he’d always loved game, and in 2009 acquired an additional 12,300 acres to collect African antelopes—sable, kudu and eland. In 2013, he added rhinos. By then, the poachers’ war on the rhino was in full fury, topping 1,000 animal deaths a year for the first time. The thieves were hunting mostly in Kruger National Park and the areas around South Africa’s eastern border with Mozambique. But as anti-poaching measures there improved and the price of rhino horn kept soaring, to tens of thousands of dollars a kilogram, the poachers began expanding into new territory.

They first hit Van Niekerk’s place, deep in the interior, in January 2017, came again the next month, and a third time that April. They killed six rhinos, left four with gunshot wounds and orphaned two calves. They would wait for a full moon, a pattern so set it has become known as a “poachers moon,” and Van Niekerk’s well-being waxed and waned with the lunar cycle. He’d lay awake, waiting for his phone to ring or feeling haunted by gruesome memories of an 18-year-old female that had been mutilated with an ax. Her 3-month-old calf burrowed into her side. “It was five or six hours before we could take him to a rehabilitation center,” Van Niekerk said. “He just lay next to his mommy, moaning, and didn’t move. It was pathetic.”

The poachers came again that June, but this time Van Niekerk’s security guards were there. A firefight broke out, and they wounded two poachers, who left a trail of blood for the guards to follow. The guards eventually captured five out of the seven poachers and handed them over to the police. But Van Niekerk had had enough.

“I couldn’t keep putting my people at risk,” he said. “I couldn’t go to their families next time and tell them it wasn’t the poachers but one of our guys who got shot.” He paused. “I am angry, and I know tomorrow when they take the rhinos away I will be even more angry. But I also know I will sleep better when they’re gone.”

**********

At the beginning of the 20th century, Africa’s rhino population was about 500,000. There are two species, called white and black, with the white further divided into northern and southern subspecies. (Three other rhino species exist, in India, Sumatra and Java.) Van Niekerk’s rhinos are southern whites. The origin of “white” is uncertain, but some sources say it’s a mistranslation of the Dutch word wijd, meaning wide, because whites have wide, flat mouths, adapted for eating grasses. They grow to 5,000 pounds and live to 50 years. They are gentle to a fault. There are stories of rhinos that put up hardly any resistance as poachers hacked at their spines with axes. Black rhinos are smaller than whites, growing to 3,000 pounds, have rounder mouths with lips adapted for eating leaves, and are more aggressive, known for flashes of temper. And as the white isn’t white, the black isn’t black either. Both are gray.

The rhino population in Africa has fallen by more than 95 percent since 1900, to just 21,000 southern white rhinos and 5,000 black rhinos; 80 percent of those animals are in South Africa’s game reserves and on ranches like Van Niekerk’s. The northern white rhino subspecies has been reduced to its last two members, both females; the last male died this past March at age 45 at a reserve in Kenya, a death lamented around the world. Scientists are hurriedly researching ways to sustain the subspecies (see opposite page). The main, if not only, cause of the collapse of the northern white rhino, and the devastation of black and southern white rhinos, is wanton killing of the animals, primarily for their horns.

The illegal trade in African rhino horn, worth several billion dollars a year, is driven by demand in Asia, where horn is pulverized for use in dubious medicines or fashioned into ornaments and objects. A white-rhino horn typically weighs about four kilograms, according to Phillip Hattingh, who investigated the Asian black market for his upcoming documentary film The Hanoi Connection; it’s $10 per gram for the brittle parts that are pulverized and mixed into potions and $180 per gram for the hard black core used to fashion trinkets such as bangles, bracelets, even wedding rings. International crime syndicates control the trade. A poaching team—the several men who actually do the grisly job—may receive as much as $10,000 per horn.

Since 2008, poachers have slaughtered almost 8,300 rhinos. The numbers are especially tragic given that the horns—the African rhinos have two—can be removed without killing the animal. The horn is not bone, like an elephant’s tusk, but keratin, the same material as fingernails and hair—it can grow back as long as it’s cut above the germinal layer where it connects to the facial plate. Nonetheless, poachers killed 1,028 rhinos in 2017, or an average of nearly three per day; at this rate, some experts predict, all African rhinos will be gone from the wild in ten years.

Conservationists want to save rhinos by taking them from where they are threatened and placing them where they have a better chance of survival. “The main reason for moving rhinos is strategic,” Richard Emslie, scientific adviser on rhinoceros for the International Union for Conservation of Nature, told me. “You manage rhinos like an investment share portfolio: You don’t want all your investments in one place.”

Even so, conservationists remain divided over some issues, particularly whether to dehorn rhinos—and what to do with the horn. Proponents of the practice say a controlled trade in horn is the only way to ensure that the rhinos are more valuable alive than dead, and the revenue would enable owners and breeders to protect animals whose security is otherwise unaffordable; opponents say it mutilates animals and deprives them of their primary means of defense, at least temporarily. In 2015, two breeders in South Africa, supported by many scientists, sued the government to lift its moratorium on trading rhino horn, arguing that the measure had inadvertently created the black market. After protracted litigation, South Africa’s highest court in 2017 came down on the side of dehorning, lifting the ban on trading horn within the country. That decision, however, has had limited effect: Few legal trades have been completed, and international trading is still banned by treaty.

More broadly, the conservation movement in much of Africa must also contend with the conflict between protecting wildlife and meeting the needs of local people. The continent has the world’s fastest-growing human population, projected to increase by 1.3 billion by 2050, to 2.5 billion, according to the United Nations. African governments have their hands full providing roads and schools, hospitals and food. Spend time among impassioned wildlife lovers, and you may hear some wince-inducing views, typified by what one wildlife executive told me after several drinks: “Africa doesn’t have an animal problem! It has a people problem. We don’t need to cull animals. We need to cull people.” Some people at our table raised their glasses in endorsement.

When I mentioned this comment to Les Carlisle, a conservationist who would help manage the translocation of Van Niekerk’s rhinos, he chafed. “Absurd,” he said. “On the whole, conservation has done absolutely nothing for communities around them. But we know this: When there’s benefit to the community, wildlife crime is minimal.” Conservationists, he said, “have to look after the animals and the land and, most important, look after the people. You need to work with them. But it’s not something you can achieve overnight.”

Yet when there’s an opportunity to move some rhinos to a better place, things happen almost that fast.

**********

Relocating a rhinoceros, you might imagine, is no easy feat. “I never really enjoyed putting rhino into boxes and sending them anywhere,” says Dave Cooper, whose job as the veterinarian at the parks in -KwaZulu-Natal province has also included conducting forensic rhino postmortems. “I felt sorry for them. What has changed now is, when I put them into a box I’m saving them.”

The Last Rhinos: My Battle to Save One of the World's Greatest Creatures

When Lawrence Anthony learned that the northern white rhino, living in the war-ravaged Congo, was on the very brink of extinction, he knew he had to act.

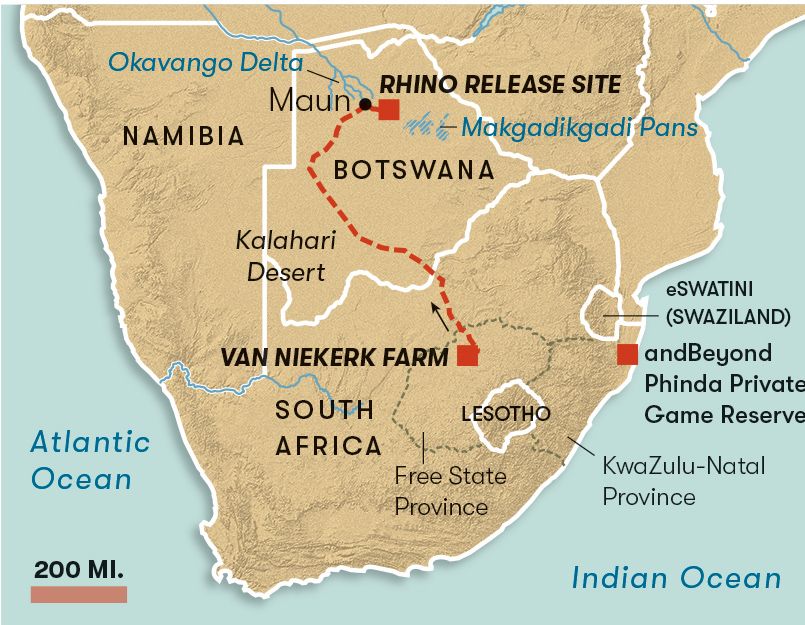

The attempt to move Van Niekerk’s rhinos was organized by Rhinos Without Borders, a partnership formed by Dereck and Beverly Joubert, documentary filmmakers and founders of Great Plains Conservation, and Joss Kent, CEO of the luxury safari outfitter with the compound name andBeyond. Since 2015, the two organizations have raised $4.5 million to acquire and relocate up to a hundred rhinos and monitor them for three years. This would be the largest and farthest single move to date, involving Van Niekerk’s 32 rhinos and another eight from Phinda, an andBeyond reserve in -KwaZulu-Natal. The destination was some 800 miles distant, in a remote part of Botswana.

As the sky darkened over Van Niekerk’s farm the temperature dropped to a wintry chill, and the relocation team members gathered around a fire pit to go over the plan. They included veterinarians, a doctoral candidate doing research, a helicopter pilot, drivers and people who by necessity had mastered the paperwork for the permitting and export process. “We’ve worked it out,” Carlisle told me. “When the weight of the paper is equal to the weight of the rhino, they’ll let us go ahead.” They broke out coolers and roasted some beef and the South African sausage known as boerewors.

I went out with a pair of security guards scouting for poachers, who might have been tipped off to the operation and poised to strike. Our truck had spotlights and light bars on the front and sides, a radio, an onboard camera and semiautomatic rifles. The men wore flak jackets and carried side arms. Their background was in conservation, but they’d also been trained in vehicle interception, bush tracking and combat. “We’ve had to become paramilitary,” said one of them, who asked to be identified only by his first name, Brett. “Sometimes,” he added, “when I’m interviewing guys we captured, I’m just glad there’s a barrier between us.”

By now the moon was just a thin crescent, and we spent an hour driving the perimeter in the darkness. When we returned to the farmhouse we heard that Van Niekerk’s other security people, out in the field, had been reaching for their rifles before someone thought to call to let them know that the vehicle heading toward them was us.

The night wasn’t nearly over when it was time to get up, and before first light we arrived at the 2,400-acre enclosure where Van Niekerk had penned his rhinos. The flat expanse of tall grasses bleached by the sun and the dry winter season was sectioned off by high chain-link fences and barbed wire.

The day’s task was to get 15 rhinos into separate metal containers, load the containers onto four flatbed trucks, and hit the road in a convoy including the flatbeds, the security guards’ truck and a pair of minivans. A second operation would follow ours to transport Van Niekerk’s remaining rhinos.

“I’ve done it many times, and I’m nervous every time,” said Grant Tracy, a game capturer who was managing the relocation. “The older you get, the more you realize how much can go wrong and how it can all spin out of control very quickly.”

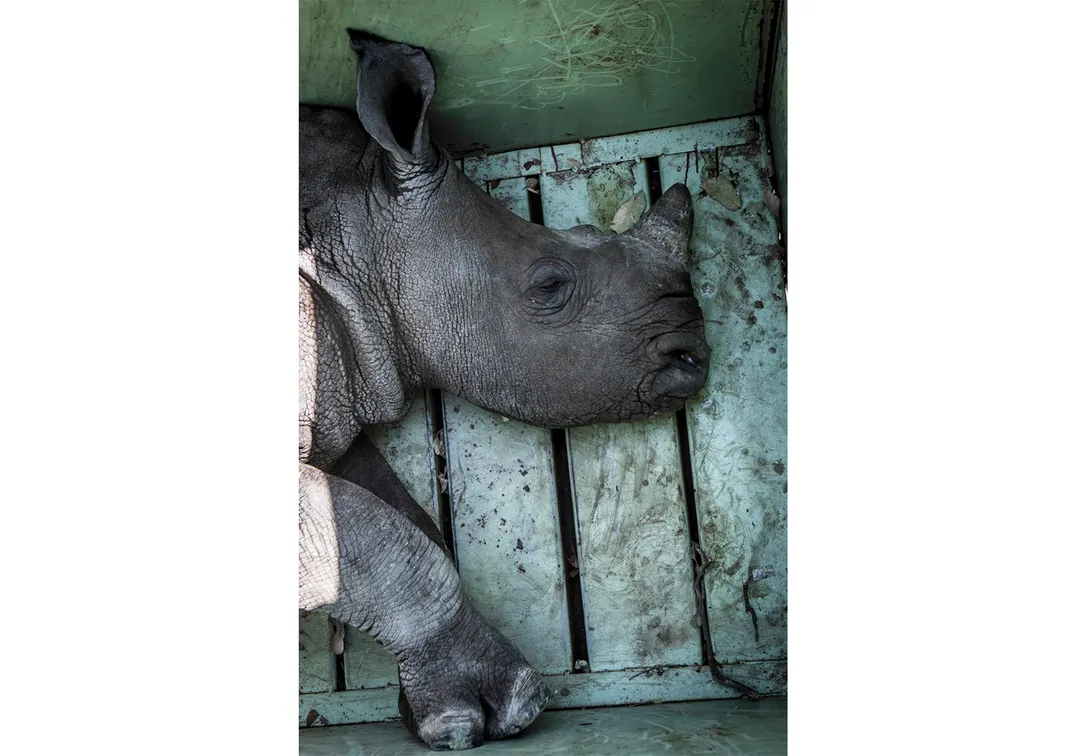

At dawn, an R44, a nimble helicopter, its doors removed, hovered just above the rhinos. One of the vets leaned out with a dart gun to deliver a dose of M99, a sedative thousands of times stronger than morphine. It hit a female rhino’s rump with a thwack; a moment later she stood still, stunned and quivering, as if she were trying to move and couldn’t understand why she couldn’t.

Her eyes, tiny in the massive casement of her head, darted back and forth. Workers in blue jumpsuits and expedition leaders in their muted safari colors and wide-brimmed hats descended on her, laying hands on her face, her horn, her flank. Once they got a blindfold over her eyes, she relaxed. A half-dozen workers tipped her onto her side. A researcher drew a blood sample into a syringe so they could monitor blood levels of stress hormones, among other things. It fell to someone else to put on a plastic sleeve the length of his arm and reach into the anal canal to extract a fist-size stool sample. Another person notched the rhino’s ears—a form of identification.

All the while, the workers kept their palms on her flank, face and the hump at the nape of her neck, to reassure her. I stepped in to touch her, too. She was a mass of textures. Her back was rough. The armor on the top side of her trunk was thick, latticed in a pattern of rectangles sweeping down to the underbelly, which was full and soft. Heavy folds fell over her legs, which look jammed in, like pillars holding up a bulbous building.

Van Niekerk needed all his strength to wrest open her mouth. Her upper lip was velvety, hot and tender. There was a big rough exterior ridge along the top of her mouth, and inside was another ridge of rough bumps; the only teeth were molars. Her ears were erect; the skin behind them was as soft as an ancient and well-oiled baseball mitt. Her tail, so small, looked better suited to a piglet.

And then, of course, the object of so much grief: the horns. Van Niekerk took a hacksaw and removed the bigger horn. It had to come off before the rhino went into the container, or she might break it and injure herself. The stump felt heavy and smooth.

The workers got her back on her feet, tying a rope to each of her hind legs and leashing her head, pushing and pulling, making judicious use of a cattle prod to maneuver her toward the metal container. The rhino was still sedated, and she high-stepped even though her four legs weren’t quite in sync. At the edge of the gangplank—the last step before the metal container—she swung her head and sloughed off her captors. They regrouped, tugged, heaved and hoed. Just as they got to the door and could see the end of things, she sidestepped it and started taking big strides, as if to break into a gallop. Amid a lot of shouting I took cover behind a pickup truck until the captors reined her in, and this time she disappeared into the container. From above, a worker released the metal door, which dropped like a guillotine. Reaching through an opening in the top of the container, another person removed the blindfold.

Twenty minutes later, after the crew had moved on to the next rhino, we got word that she had busted out. The container’s front door was missing a metal pin to secure it. The crew had to start all over with her.

And so it went with the 15 beasts.

A mechanical loader lifted the containers onto the four flatbeds, which formed into a convoy with the two minivans and the private security guards in the pickup. It was almost 3 in the afternoon. After nine hours in the field, we could start the journey to Botswana.

**********

Seven hours later, at the Botswana border, our private security force peeled away, and soldiers from the Botswana Defence Force took their place.

Botswana is about the size of Texas, but it has just 2.25 million people, mostly on its eastern flank. The rest is a barely populated wilderness stretching across the Kalahari Desert, the Makgadikgadi Pans, a series of salt pans the size of Belgium, and the fertile, paradisiacal Okavango Delta. The vastness and austere beauty can leave you slack-jawed, and tourism is now the country’s second-biggest industry, after mining.

As we set out on the Trans-Kalahari Highway, the security posture changed. In South Africa, security relied on inconspicuousness and discretion. Here, it was about boldness. When the convoy stopped to refuel, soldiers spilled out of their vehicles and formed a perimeter while holding their rifles. The handful of local men and women hanging out at the gas-station convenience store seemed happy for the break in the humdrum. The temperature had dropped, and everyone reached for fleece. A vet climbed onto the tops of the containers to check on the rhinos, who protested their kidnapping by banging against the container walls, sending metallic thuds into the night.

Back on the road, seeing only as far as the spray of the headlights, we kept to about 50 miles per hour because of the risk of livestock loitering. By noon we reached Maun, the gateway to the Okavango Delta. We had only about 30 miles to go, but now had to cross swampland. The big flatbeds were too heavy. A forklift moved each container onto a smaller truck. We entered the delta where it met the Kalahari, bordered on two sides by rivers and laced by streams that created little islands where whole civilizations of termites had built mounds that peaked like ziggurats. The trucks plunged into pools of water that rose above the headlights, but we made it through.

We reached the release site at nightfall, some 30 hours after leaving Van Niekerk’s farm. Each rhino was darted and led out of its container, tipped onto its side and had more blood drawn. Workers belted a GPS monitor around an ankle of each animal.

Now there were nearly a hundred people on hand. Among them were the Jouberts, who had envisioned this move, and Map Ives, director of Rhino Conservation Botswana, who had once worked with Wilderness Safaris, a tourism company that initiated rhino repopulation efforts here in the early 2000s. They rolled up their sleeves and got to work with the others, well past midnight.

Seven rhino bulls lay still on the ground like big gray boulders. The four cow-calf pairs would spend the night in a pen that looked like a little stockade. They were darted with a dose of antidote, and their blindfolds were removed. One by one, they stirred and stood upright. Car headlights shone gold on their gray hides. The rhinos sniffed their heavy sniff. Three of the bulls huddled as if to check that each one was okay. The other four came to. A cow got to her feet. And then Van Niekerk’s rhinos took the first steps they’d made on their own in 40 hours, lumbering, heavy-limbed, beyond the headlights and into a forest of darkness.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.