The Deadly Cunning of the Black Widow’s Color Scheme

Why did the spider evolve to have that crimson hourglass on its back?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/7d/f37d86da-f7ad-4f95-a360-5b454b1bee56/may2016_e01_phenom.jpg)

If your PhD adviser suggests that you spend more time with a creature famed for its incapacitating neurotoxins, is he trying to say it’s time for a career change? Nicholas Brandley didn’t think so, and embraced the study of black widow spiders. “Their fangs don’t even usually pierce human skin!” he says in an effort to be reassuring.

While widows are indeed among the most venomous arachnids in North America, Brandley, who now teaches at Colorado College, was more curious about the distinctive red hourglass on their bellies.

Many insects use bright red coloration to ward off predators, but most of those bugs are red all over, with maybe a scattering of black spots. (Think ladybugs, which contain a nasty-tasting chemical.) North American black widows are solid black with just the crimson hourglass and, in some species, a few red spots. As birds also tend to be leery of high-contrast bright colors in places where they don’t expect them, Brandley guessed the hourglass was a bird deterrent, since widows point it skyward when dangling in their webs.

But if crimson makes predators jumpy, why weren’t the spiders even redder? Brandley suspected that a second selective force was at work, involving the spider’s prey. Had evolution finessed the spiders’ color scheme to warn off birds without also alerting beetles?

The first part of his experiment, started at Duke University, required plastic widows made with a 3-D printer. He painted “Berry Red” hourglasses on some, left others plain black and placed both types on bird feeders. The birds attacked the unadorned spiders three times more often.

When Brandley compared the widows’ hourglass colors with the vision capabilities of insects and birds, he found that birds can detect reds three times better than bugs can. So he thinks widows evolved a discrete marking instead of becoming red all over, because birds could see it easily but not insects. “Here’s a warning signal that has been shaped by something other than just predators,” Brandley concludes. “Signals aren’t given in a vacuum.”

In another test, Brandley, armed with foot-long forceps, installed two types of live black widows in terrariums. The species with extra red spots on its back tended to spin webs higher up than the other spiders. Because of its lofty habitat preference, that species likely risks predation from above and below, and may bear extra warning spots at a cost to its own hunting. Missing a meal or two sure beats becoming one.

Related Reads

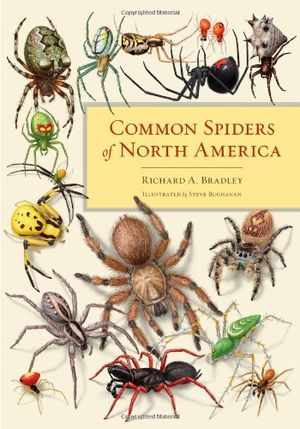

Common Spiders of North America