Deciphering the Weird, Wonderful Genetic Diversity of Leaf Shapes

Researchers craft a new model for plant development after studying the genetics of carnivorous plants’ cup-shaped traps

:focal(990x780:991x781)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/50/0650b414-8710-4bb2-8fe7-afd8a7c147ed/diverse-leaf-shapes-john-innes-centre.jpg)

Around the globe, plants have evolved to use their leaves for many purposes: broad, flat fronds to soak up sunlight, hardy needles to withstand the elements, even intricate traps to snap up unwitting insects. But the biochemical processes by which plants sculpt their many leaf patterns have remained something of a mystery to scientists.

Now, a study led by researchers from the John Innes Centre in England, a plant science institution, proposes a new way of understanding the genetic steps that allow leaves to grow into their particular shapes. The study, published this month in Science, brings together molecular genetic analysis and computer modeling to show how gene expression directs leaves to grow.

Many plant scientists see leaves as being broken up into two domains—the upper leaf, or adaxial, and the lower leaf, or abaxial—and have looked at this separation as the key to producing a wide variety of leaf forms. The two regions have different physical properties and are also marked by variations in gene expression. Even though the genetic makeup might be the same across these regions, their expression (whether they’re turned “on” or “off”) differs.

Previous models have focused on the specific place where the boundary between these domains meets the surface at the leaf’s edge, considering it the central spot that induces cell division and controls growth, says co-lead author Chris Whitewoods, a John Innes Centre researcher. One complicating factor with this line of thinking is that cell growth and division are spread more or less evenly across the leaf, not just at this margin, meaning some signal must provide growing directions to all parts of the leaf.

Whitewoods and his team propose that the boundary between the two genetic regions of the adaxial and the abaxial creates polarity fields throughout the leaf to direct growth. Though these polarity fields don’t run on electromagnetic charges, they function in a similar way, with cells throughout the tissue orienting themselves in the fields like tiny compasses.

“Our model, specifically in relation to the leaf, is that this boundary between two different domains … makes this polarity,” Whitewoods says. “And if you move that boundary, then you can change leaf shape from being flat to being cup-shaped, like a carnivorous plant.”

Past work from this lab, led by Enrico Coen, has studied this idea of a polarity field, but the new model adds a second polarity field to simulate growth in three dimensions, Whitewoods says. The two fields run perpendicular to each other, with one from the base to the tip of the leaf and the other from the surface to the adaxial-abaxial boundary.

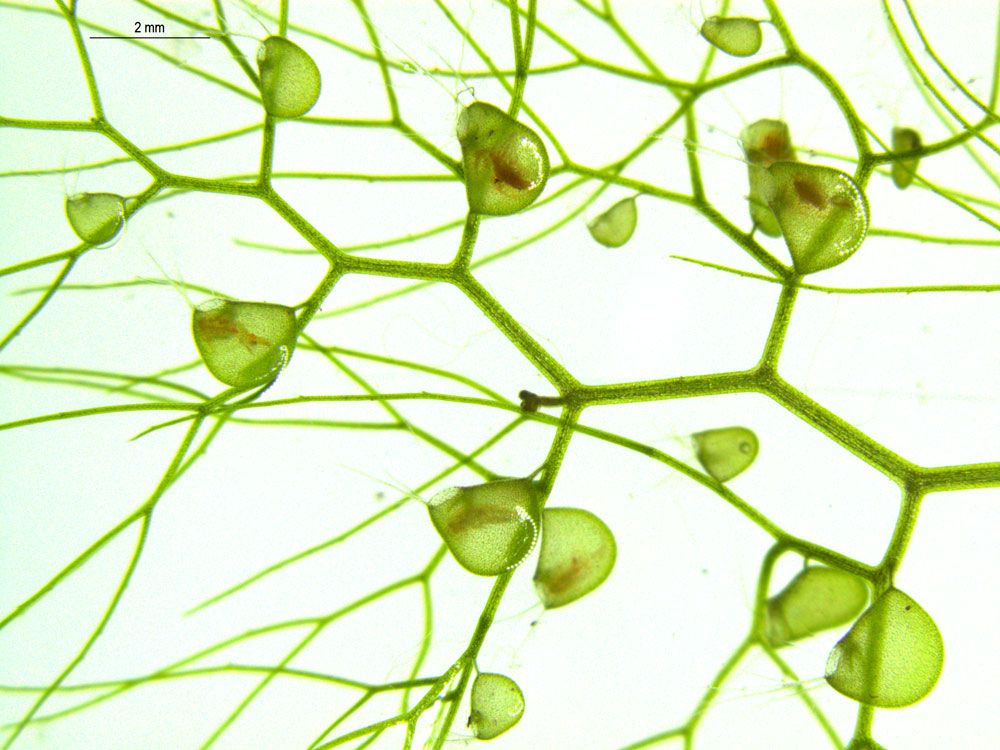

To understand the mechanism, the researchers focused on Utricularia gibba, also known as humped bladderwort—an aquatic carnivorous plant that captures its insect prey in tiny, cup-shaped traps.

Carnivorous plants make for intriguing evolutionary subjects because their complex cup shapes have developed in multiple species, says co-lead author Beatriz Goncalves. And several characteristics of U. gibba make it a good candidate for study: It has a small genome, its thin trap walls are easy to image, and it grows well in the lab.

Researchers induced the expression of one particular gene—UgPHV1, which previous studies have shown is important to forming flat leaves in other plants—across parts of the plant tissue where it would normally be restricted. They found that forcing this gene to be overexpressed in still-developing U. gibba interfered with how the plant formed its cup-shaped traps and, if induced early enough, prevented traps from forming at all.

Restricting this gene’s activity in some parts of the leaf buds, the authors concluded, is an essential step in trap development. This finding supports the idea that changing the gene expression at the domain boundary, or edge of the leaf, affects the resulting shape of the entire leaf.

To supplement these lab findings, the third lead author Jie Cheng led the development of a computer model to simulate leaf growth. At its core, the computer model is a 3-D mesh of connected points that pull at each other like parts of a plant tissue. The virtual leaves grow based on the polarity fields established by the upper and lower leaf domains—or, in the case of carnivorous plants, the corresponding inner and outer regions of the cup trap.

Using this simulation, the researchers were able to replicate the growth of U. gibba cup shapes as well as many other common leaf shapes, including flat leaves and filiform needles. To do so, they only needed to change the position of the domain boundaries, which are determined by gene expression in the adaxial and abaxial, to affect the corresponding polarity fields, without specifically directing growth rates across the entire leaf, Goncalves says.

“The minimum amount of information you put in the model, then the less you push it to do exactly what you want—it actually reveals things to you,” Goncalves says.

Using 3-D modeling in combination with the genetic analysis is an interesting proof-of-concept approach for the proposed growth mechanism, says Nat Prunet, a plant development researcher at UCLA who was not affiliated with this study. However, he says, the computer models can only tell us so much, as virtual growth doesn’t necessarily rely on the same parameters as real biological growth.

Still, the study provides new insight into plants’ evolutionary history, showing that small tweaks in gene expression could result in vast diversity among leaf shapes, Prunet says. Within the polarity field model, even minor changes in the genetic expression of the upper and lower leaf domains can dramatically transform the direction of leaf growth.

“All evolution would have to do to make a new shape would be to, instead of expressing a gene over a big area, express it over a smaller area,” he says. “So instead of having to evolve a new gene function or completely new genes from scratch, you can just change the expression of something and make a new shape.”

Using the new model as a basis, Goncalves and Whitewoods say they plan to develop a more detailed picture of how the domain boundary controls growth and test how broadly the mechanism they’ve proposed can be applied to different plants and structures.

After all, many mysteries still remain in the incredible diversity of plants—organisms Whitewoods likens to strange little “aliens” whose beauty and intricacy often go underappreciated.

“People who work with plants have this sort of love for the underdog,” Goncalves says. “Most people pass them by … but they're doing such a hard job at so many things. It's just fascinating.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Maddie_3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Maddie_3.jpg)