Deep Trouble

Coral reefs are clearly struggling. The only debate for marine scientists is whether the harm is being done on a local or global scale

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/coral3.jpg)

Research has shown that, with paltry few exceptions, the planet's coral reefs have experienced a prolonged, devastating decline in recent decades. But determining which factor, or factors, is most responsible for that decimation has proved vastly more difficult. The result has been an ongoing, often contentious debate between those who believe that local factors such as overfishing and pollution are most to blame, and those who say global climate change is the main culprit. Solving the debate could be critical to determining how best to direct efforts and resources for restoring reefs, but definitive answers remain elusive, as two recent studies illustrate.

To help answer some of these questions, a team of researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography set out in a converted World War II freighter in September 2005 to study reefs in the South Pacific's remote Line Islands. They have since returned to the area twice, most recently this past August.

The reefs they are studying follow a gradient of human influence, beginning with those near Christmas Island, with a population of roughly 10,000 people, and ending some 250 miles away at Kingman Reef, a U.S. protectorate that has never been inhabited and has been the target of very limited fishing. If global influences are the dominant factor in reef decline, the team hypothesized, then isolated Kingman should look as bad as, or worse than, Christmas reefs. But if human influence plays the larger role, then Christmas reefs would be in worse shape than Kingman.

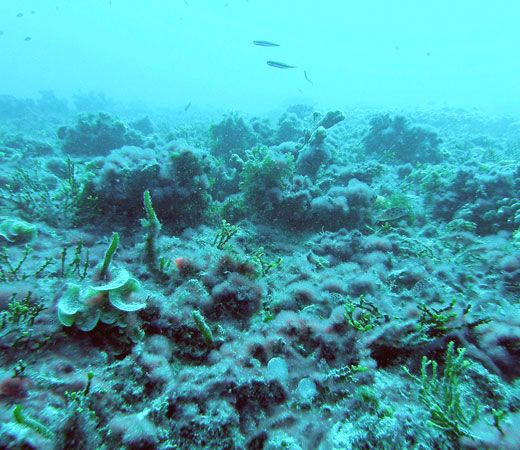

The team completed uniquely comprehensive reef surveys at five areas, studying everything from bacteria to top predators to the corals themselves. Healthy corals take on the color of the microscopic algae living symbiotically within them, while dead corals may be white versions of their former selves, or reduced to rubble. Reefs found in the less populated areas were nothing short of awe-inspiring for their beauty and colorful inhabitants, most notably a massive numbers of sharks. "I realized, I'm no longer clearly the top of the food chain, I'm a member of the food chain," says study leader Stuart Sandin of his first dives.

The sharks were more than a humility check, however; the large number of them is actually indicative of good reef health, the researchers believe. The standard ecological model calls for a small volume of predators at the top of the pyramid, with simpler organisms comprising a much larger base. Instead, at the most remote Line Islands reefs, such as those at Kingman and Palmyra, the team found that fish made up some 80 percent of the reefs' total estimated biomass—half of which were sharks. Historical descriptions by whalers of some of the areas studied speak of trouble rowing because sharks would bite the oars, Sandin says, perhaps suggesting that, in the past, shark populations were even larger, and reefs therefore even healthier.

Though analyses are still underway, the researchers believe that this inverted ecological pyramid, possibly a sign of naturally healthy reefs, is the result of minimal fishing by humans.

Overall, the team found the Line Islands reefs farthest from Christmas Island to be the healthiest, with more coral cover and less macroalgae, or seaweed, overgrowing the reefs. Macroalgae can smother reefs, fill otherwise habitable nooks and cover food sources. One of the unique aspects of the Scripps work was that the team came equipped with a genetic sequencer that enabled them to analyze the types of bacteria in reef samples. These tests led to the conclusion that macroalgae secrete substances that support higher concentrations of bacteria, some of which can cause coral disease and death.

There is ongoing debate whether algae overgrowth of reefs is driven by pollution in the form of nutrients, chiefly nitrogen and phosphorus, which fertilize growth, or overfishing, which removes grazers that would otherwise keep macroalgae growth in check. Sandin believes their data show overfishing has driven algae spread at the reefs because nutrient levels were only slightly higher near Christmas Island, and levels at all reefs were higher than the threshold some researchers have proposed triggers algae overgrowth in other parts of the world. "But, I will agree that the jury is out," Sandin says. "We don't have conclusive evidence."

Researchers on all sides of the debate agree that today there is no such thing as a truly pristine reef, in large part because global warming has been linked to increased incidence of coral bleaching, which is caused by abnormally high water temperatures. Bleaching causes coral to lose the algae they depend on for most of their nutrition, making them more susceptible to disease and even killing them in some cases.

But Sandin and his colleagues suggest that human factors, whether pollution or overfishing, likely weaken reefs so that they become more susceptible to global-scale problems. Studies have shown that Kingman Reef has experienced very little bleaching—and significantly less than the reefs near Christmas Island. If global influences are the main driving force, Sandin says, then reef health should have been roughly the same at all the sites.

John Bruno, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, believes that while there may be isolated cases where reef health seems to correlate with proximity to human populations, a broader view tells a different story. "My general impression is that the global influences seem to have much stronger impact, but I'm really careful not to totally write off local impacts," he says. Bruno and his colleagues recently analyzed various research surveys conducted at more than 2,500 reefs. They found no overall correlation between reef condition and distance from human populations. However, ocean dynamics are so complicated that simple distance may not be a good measure of human impact at many locations, he says. Commercial fishing, for example, can be quite concentrated far from any human settlement.

Bruno and a large team of collaborators are working to develop a computer grid that more accurately estimates human influence at points around the globe, taking into consideration currents, fishing exploitation and other factors. For their part, the Scripps team continues analyzing their massive dataset from the Line Islands, and will return there in 2009. But, if past results are any indicator, the debate is likely to extend well beyond then—as is reef decline.

Mark Schrope, a freelance writer based in Melbourne, Florida, writes extensively on ocean topics.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)