Did Scientists Just Discover a Cure for Sunburn Pain?

Researchers pinpointed the molecule responsible for the searing pain of a burn, and may have found a new way of eliminating it entirely

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Surprising-Science-Sunburn.jpg)

Go ahead, apply sunscreen when you head outside this summer. Re-apply it over and over. Despite your best efforts, there’s a good chance you’ll eventually get burned.

If nothing else, you’re likely to miss a spot here and there. And because it naturally wears off over time and comes off even faster when you’re wet or sweaty, medical experts recommend re-applying it as often as once an hour for full coverage—a schedule few sunbathers care to follow.

You’ll probably be told to apply aloe vera gel to numb the pain. Controlled studies, though, have found no evidence that the plant extract is actually effective in treating sunburn pain, conventional wisdom notwithstanding.

Until recently, all this meant that spending hours under the Sun likely meant some pain—and once a burn happened, the searing pain was inevitable. But new research by a group of scientists from Duke University may signal the arrival of an entirely new type of sunburn treatment, based on our growing understanding of the molecular activity that occurs when we get burned.

The team recently discovered one particular molecule in our skin cells, called TRPV4, that is crucial for generating the pain associated with sunburn. And when they blocked the activity of TRPV4—either by breeding special mice that lacked the molecule or applying a special compound that inhibits TRPV4—they found that the painful effects of sunburn were significantly reduced or eliminated entirely.

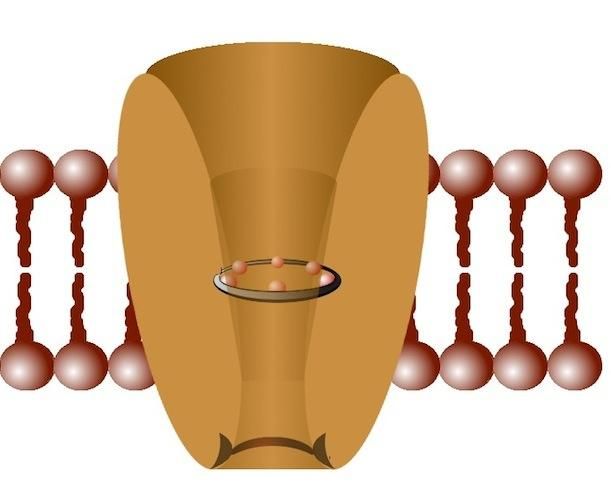

They began their research, which was published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by closely examining TRVP4, a protein known to be involved in the transmission of many sorts of skin pain and itching. The protein is embedded in the membranes of our skin cells and serves as a channel that allows certain molecules (such as calcium and sodium) to permeate the membrane and enter the cell.

To test whether it was involved in sunburn pain in particular, the team genetically engineered mice that lacked TRVP4 in their skin cells and exposed them, along with normal mice, to controlled amounts of UV-B rays (the type of ultraviolet light that causes sunburn). The latter group, alas, suffered from bright red burns and reacted to tests on their hind paws (which are hairless and most closely resemble human skin) in a way that indicated they were experiencing severe pain. But the experimental group, which lacked TRVP4, showed greatly reduced evidence of burns and no skin sensitivity.

When they examined cultured mouse skin cells on the molecular level, they confirmed the role of TRVP4 in transmitting sunburn pain. They found that when UV-B rays hit skin cells, they activate the TRVP4 channels, which then allow calcium ions to stream into skin cells. This, in turn, causes a molecule called endothelin to follow into the cells, which leads to pain and itching.

Genetically engineering humans to not experience pain when they get sunburned is, of course, a pretty far-fetched idea. But what the researchers did next could someday change the way we treat burns.

They mixed a pharmaceutical compound (called GSK205) that is known to inhibit TRVP4 into a skin disinfectant and brushed it onto the skin of normal, non-engineered mice. After these animals were exposed to UV-B light, they showed greatly reduced signs of burning and pain.

This is obviously a far way off from next-generation sunburn treatment—for one, is still hasn’t been tried on humans. But the researchers did confirm that the TRVP4-related pathway in mice is similar to the one that activates when we get burned: they also studied cultured human skin samples and measured increased activation of TRVP4 channels and endothelin in cells after UV-B exposure.

Of course, there’s a good reason for the pain from a burn—it’s our body telling us to avoid excessive Sun exposure, which causes genetic mutations that can lead to skin cancer. So even if this research led to an effective way of completely eliminating the pain from a burn, recommended practices would still involve applying sunscreen in the first place.

Wolfgang Liedtke, one of the study’s authors, notes that TRVP4 has many other roles in the body apart from transmitting pain and itching, so more research into the other effects of inhibiting it is needed before the concept is tested on humans. But eventually, for the times that you forget to apply often enough and do get burned, a compound that shuts down TRVP4—or other compounds with similar activity—could be quite useful.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)