Dissecting Moth Genitals In the Name of Science

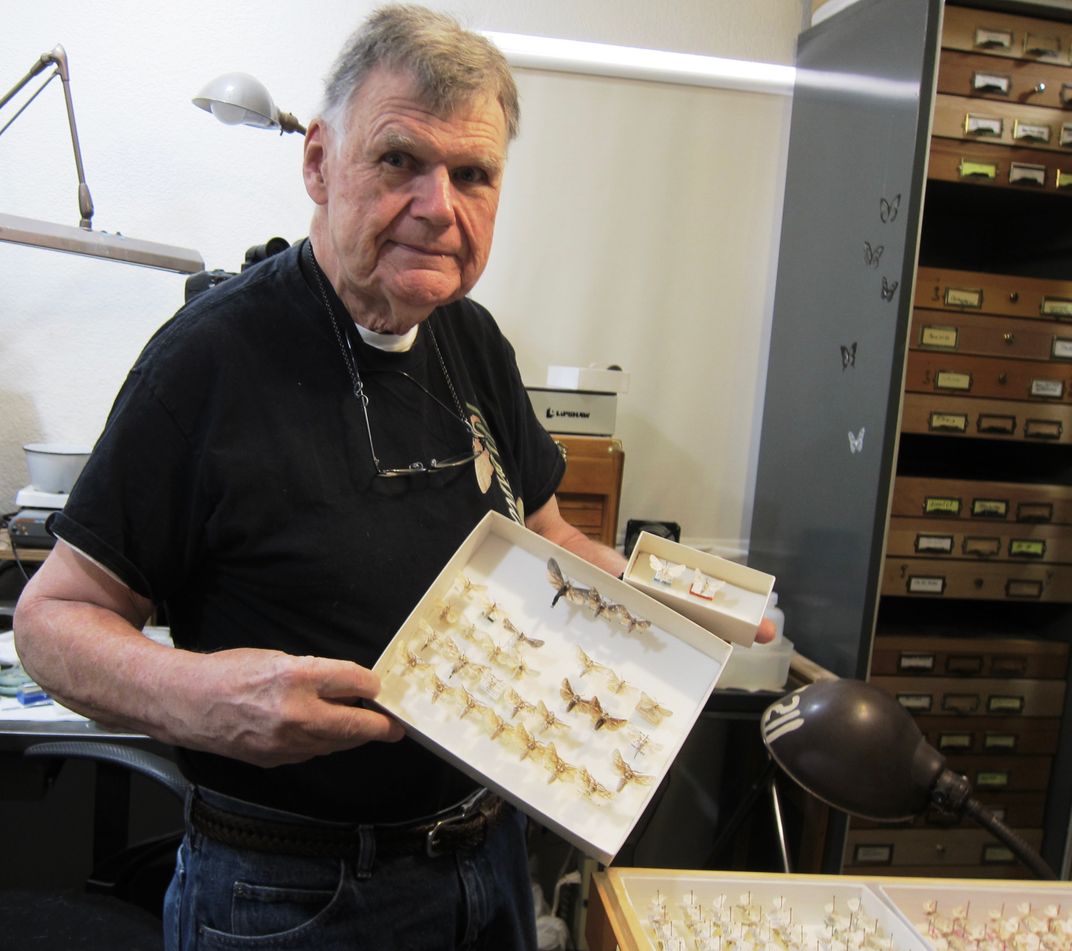

How “moth evangelist” Eric Metzler uncovered hundreds of moth species in the barren dunes of New Mexico

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/6c/326c5418-17e2-4bd3-9f3f-bd5aca6404a8/white_sands_image5.jpg)

It’s just after sunset, and I’m sitting in a truck amongst the bleached white dunes of New Mexico’s White Sands National Monument, waiting for darkness to fully fall. I’ve ventured here with entomologist Eric Metzler in pursuit of some of the most richly varied creatures that emerge from these dunes: moths.

Once it’s dark enough, we walk to a series of black lights we have strung to a clothesline to attract the silent flappers. Under the cool purple glow of the setup, I spot our first specimen fluttering toward me on the ground.

“Excellent!” Metzler says, immediately recognizing the species. “That’s whitesandensis, fantastic,” he adds as he hands me a glass vile and cork to collect it.

Metzler has been regularly collecting moths here since 2007 on behalf of the National Park Service. A retired entomologist who still holds adjunct positions at Michigan State University and New Mexico State University, Metzler was thrilled to discover Protogygia whitesandensis — the first native species of moth ever found in White Sands — during the first year of his study. Since then, he has found an astounding 600 species, including more than 50 others entirely new to science that he has catalogued in Smithsonian’s National Collections.

Why a harsh, desolate environment that receives only 10 inches of rain annually and swings between vast temperature extremes would contain such unusual diversity is still a mystery. “That’s an enormously high number, especially considering how barren the landscape is,” Metzler says. And many entomologists aren’t particularly driven to find out why, he adds, given that there are so many more charismatic insects to study.

But Metzler has committed the end of his career to painstakingly dissecting hundreds of moths to better understand their evolution. A self-described “moth evangelist,” Metzler has been captivated by these flittering insects since childhood. He started off collecting butterflies, but transitioned to moths when he got busy with a day job in high school and could only collect at night.

“I discovered there are a great many more moths than butterflies,” he says, still just as fascinated by them at age 72. “I’d never run out of moths.”

Scientists estimate that we know just 20 percent of all moth species in the world, compared to about 90 percent of the estimated 20,000 butterfly species. That’s because there are roughly 30 times more moth species, says Robert Robbins, a curator in the Smithsonian’s entomology department who studies butterfly evolution. Robbins also agrees that we know less about moths than butterflies simply because they’re not as appealing.

“Generally the image of moths is they’re hairy and eat your wool sweaters,” says Robbins.

To the untrained eye, many White Sands moths look exactly the same: roughly one-inch wingspan, with fluffy gray bodies and wings the distinct white color of the gypsum dunes. Yet to the expert eye, there are distinctions. To parse them, Metzler relies on molecular analyses to separate out the moths’ DNA. But he also uses the tried-and-true method of dissecting moth genitalia—tedious, but the best way to visually distinguish species apart.

Through this work, Metzler has come to believe that White Sands could have the highest diversity of native moths in the country, on par with rates of diversity found in other animals on the Galapagos Islands.

Robbins says Metzler’s close analysis of White Sands could contribute to our limited understanding of moth evolution. Since moths and butterflies don’t preserve well as fossils, scientists don’t have a good sense of what a “normal” rate of evolution should be. But we know the dunes of White Sands formed within the last 10,000 years, which means all of the moths endemic this region may have evolved within that timespan too.

“If all these species could evolve in 10,000 years, that’s pretty amazing,” says Robbins.

To unravel this phenomenon, Metzler spends countless hours sitting over the microscope at his home laboratory in Alamogordo, a half hour drive from White Sands. (To his appreciation, his wife Pat doesn’t mind the thousands of moths he stores in freezers in his garage and kitchen.) When I join him in his lab, he shows me a female moth the size of a toenail clipping pinned to a board, and hands me a slide containing that species’ genitals.

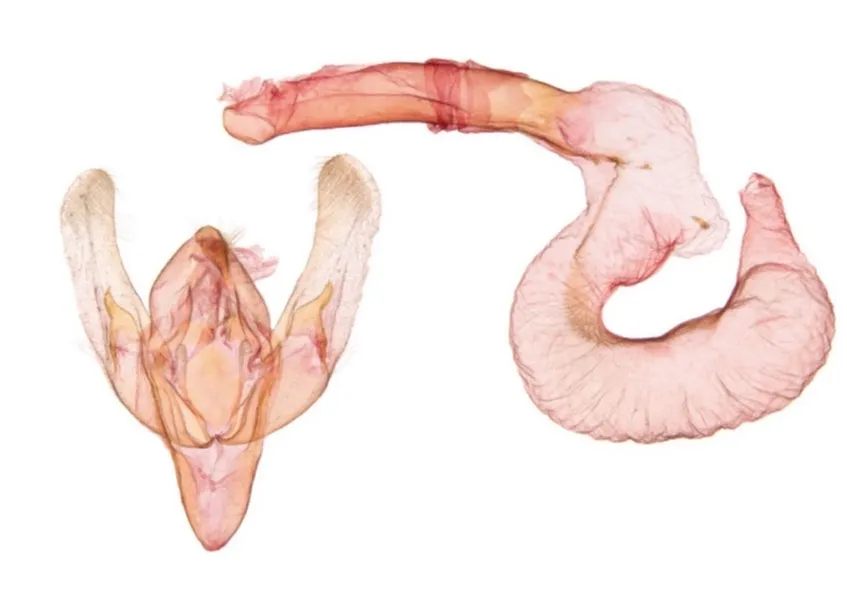

All I see is a stained smudge. “There’s actually something to that smudge when it is magnified enough,” Metzler says as he swings around his chair and arranges the slide under the microscope. When I look at it under 40x magnification, the smudge appears as a delicate jellyfish-shaped organ called a corpus bursa—the sack where the female collects sperm. “When you look at it under the microscope, it’s very attractive,” Metzler says. I have to agree.

If all goes well, Metzler can prepare a slide of moth genitalia in one day. First, he breaks off the abdomen and soaks it in potassium hydroxide, an ingredient in Drano. This dissolves all of the soft tissue, which he swipes away with a paintbrush leaving only the exoskeleton and genital organs behind—the only parts made of the hard material called chitin, the same stuff found in human fingernails and hair.

Once everything is clearly laid out and stained on slides, he looks to see if the organs from a male and female match by “lock and key,” meaning they’re from the same species. But this isn’t always discernible to human eyes. When he can’t identify a species just by looking at its organ or wing pattern, he consults his library and sends pictures to colleagues. If he’s still stumped, he sends a leg sample to the University of Guelph in Ontario—the largest moth repository in North America—for molecular analysis.

Entomologists don’t agree on what defines a distinct moth species, says Robbins, and some argue that Metzler’s moths aren’t all distinct. But by widely accepted standards of having different genitalia and molecular barcodes, he says, the 600 different White Sands moths do stand up as distinct species. “By normal standards these are distinct species and it’s not something anyone anticipated before [Metzler] moved down there,” says Robbins.

James Mallet, an entomologist at Harvard University who studies butterfly evolution and speciation, wonders if similar rates of endemism would be found elsewhere if the same type of long term study were conducted. “There are relatively few entomologists and relatively large areas in the United States to study,” he points out.

But Mallet notes that White Sands contains plant species that have been decimated by grazing and development elsewhere in the Southwest, making it a particularly valuable place to explore for new species and species associations. “I think it’s fantastic that they are studying this area, it deserves to be studied,” Mallet says.

Which makes it even more remarkable that, had Metzler not decided to retire to southern New Mexico, the moths likely would have gone undiscovered. As Robbins puts it: “We’re talking about just an incredible discovery made just purely by chance."