When he picks me up at the airport, Gary Cobb is wearing a nudibranch baseball cap, a gray T-shirt covered in illustrations of nudibranchs of various kinds, and wraparound sunglasses known colloquially in Australia as “speed dealers.” It is a bright, clear winter’s day in Mooloolaba, on Australia’s Sunshine Coast.

“I own 15 of these shirts,” Cobb, 73, says later, as we walk to a restaurant in a small shopping center. “That’s all I wear. And I do that because it’s a talking point.”

He stops in at a dive shop. A young woman behind the counter greets Cobb warmly: “He’s just a bloody legend,” she tells me. “You can quote me on that.” She draws tiny hearts on his tank and flippers.

Cobb points out a hand-painted mural depicting an undersea scene. “Now look closer—I got them to put the nudibranchs on there,” he says. And among the octopus and schools of fish, there they are: tiny, powerfully cute, neon-colored sea slugs.

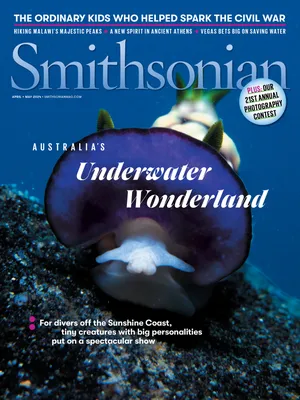

Nudibranchs (pronounced various ways, including NEW-duh-branks) are a family of sea slugs. They typically lack shells and are distinguished by their exposed gills, which is what gives them their name—naked gills. They can be as small as the half-moon of your pinky fingernail or as long as 20 inches. And they come in a gleeful variety of colors and shapes, though there are two main types. Dorids often resemble tiny rabbits, with their rhinophores, or two antenna-like protrusions on their heads, like bunny ears, and a ring of feathery gills on their backs. There is also the Spanish dancer, a slug in the form of a bright red wavy flamenco shawl. Aeolids are covered in cerata—fleshy growths that resemble anemone tendrils, only shorter. There is one aeolid that looks like a psychedelic hedgehog, and several that wouldn’t be out of place at the tip of an orchid stem. The blue dragon has long talon-like cerata on the end of perpetually outstretched arms, as though it were flying. It is really, really difficult not to compare them to Pokémon characters.

There are around 3,000 nudibranch species all over the world, from the Arctic to the tropics, but roughly a third of them are found in the waters off Australia. And Gary Cobb, a retired American expat, might just be their biggest fan and advocate.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/45/57/4557b132-09ca-4145-83ac-bfd193822142/gary_cobb_at_entry_point_preparing_to_dive_photo_by_michael_aw_awm8330_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4e/b1/4eb1549d-198e-4ee7-97a2-62346caafcaf/aerial_view_of_dive_site_at_moololaba_riverphoto_by_michael_awdji_0508_copy.jpg)

Cobb answers the phone, “Nudibranch Central, how may I direct your call?” He sells merchandise that says “Fear no nudibranch.” He runs a Facebook group called Nudibranch Central, with more than 33,000 members. Scroll down its page and you’ll find post after post of nudibranchs photographed by divers around the world—and identified by Cobb. It is a hobby that takes hours a day. He dives a few times a week at La Balsa Park, which he refers to as his “backyard,” moving slowly along the floor of the Mooloolah River just before it opens out to the sea. His average dive time is four hours, a marathon in scuba terms, though he has been underwater for as long as six.

Cobb dives for nudibranchs, he says, because it’s the “greatest value for money”—a way to spend as long as possible in the water, rather than seeing a couple of things and rushing back to the boat.

When pressed for something a little less economical, he says, “Number one: They don’t run away—everything else with gills runs away. Number two: Look at them—all that color, that variation. Number three: Not many people know about them. And that’s a challenge. I want everyone to know about them.”

He maintains a website on which he publishes detailed reports of every dive, including photographs of every species of nudibranch he sees. A post from last summer: “With a holiday today and winter clear water another dive was in order, and boy was it clear! A 190 mm Dendrodoris denisoni was found as well as two Bursatella leachii. Slime trails gave them away.” He has designed six nudibranch-identification apps, one for each of the regions worldwide where they are found. In 2006, he co-wrote a field guide to nudibranchs called Undersea Jewels.

“My life is nudibranchs,” he says. “My mission in life is to tell everyone about nudibranchs.” When we first spoke, I asked when might be a good time to visit from Sydney. “Now. There is no better time than now. So why don’t you just hop on a plane?” Two days later, I did.

Indigenous Australians have always had their own names for the creatures that live on their land and in their oceans. But only about 30 percent of Australia’s plants and animals have scientific names. Those that haven’t been identified through Western taxonomy end up falling through the net of conservation programs. “Naming is a really critical, important step in seeing biodiversity,” Lisa Kirkendale, a taxonomist and curator of mollusks at the Western Australian Museum, says. “The name triggers all of this other information.” If you’re missing that first step, she explains, it’s difficult to take any steps toward conservation. Kirkendale describes Cobb’s work as an important part of the village it takes to look after any species. Few scientists are able to dive almost daily for years on end the way Cobb has done. Without him, conservation efforts would be slower and more scattershot—possibly too slow to save some species that will now be identified, named and tracked.

Once an animal is named, its ecology can be recorded; the number living in the wild can be recorded; its evolution can be studied to determine what adaptations it has that are important to its life. It has direct impacts on conservation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/cc/15ccac9c-9fe9-4ee8-b94e-6929af3edf71/goniobranchus_geometricusphoto_by_michael_aw_awm9303_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9c/0e/9c0e8b8b-b317-451f-a9bb-b7e7a4bd565c/mapjpg.jpg)

One of the most critical parts of Cobb’s work is its regularity. He documents nudibranchs every week of the year, across seasons, over decades.

“Taking stock and doing a census is really important,” says Kirkendale, especially when it comes to proposals related to climate change or development.

Cobb works regularly with taxonomist Marta Pola, a biologist at the Autonomous University of Madrid. She discovered Cobb through his Facebook page. “I began to realize that many species that he saw very often were new to science, which obviously interested me,” she wrote over email. “For me, being in Madrid, far from the sea, it’s great to be in contact with people who are in the water almost every day and can take photos and help me to collect.”

Cobb collects slugs and sends them to museums in Australia, which then lend them to Pola, who describes and names new species and studies their evolution, morphology and DNA. Together, they have named as many as 20 new species, says Pola—“with more to come!” Without his specimens, she continues, “that would not have been possible.”

One of the species—small, white, with dark brown markings and wing-like limbs on its tail (imagine, if you will, the head of a magician’s rabbit with the tail wings of an airplane)—is named after him: Murphydoris cobbi.

Cobb was born in Miami Beach, Florida. After high school, during which his primary interests were surfing and art, he started studying design at the Pratt Institute in New York. But during his second year, his mother died by suicide. She was an alcoholic, Cobb says, and when she died, he learned that she had spent the money for his college tuition. So he left New York and went back to Miami Beach, where he worked in a bike shop for a while, before heading to California to surf, rock climb and work as a graphic designer and skydive instructor. He moved to Australia in 1990, having befriended several Australian surfers, and chose the Sunshine Coast for its proximity to the Great Barrier Reef.

In 1996, he was scuba diving in Vanuatu, in the South Pacific, when he saw something bright on the bow of a shipwreck. He moved closer: It was red with yellow polka dots, about four inches long. “It wasn’t swimming away,” he recalls. “Wow.” When he got back to shore, he learned it was a nudibranch, Gymnodoris aurita. After returning to Australia, he met a nudibranch expert on the Sunshine Coast who gave him a box of books on nudibranchs. “It was like hog heaven,” Cobb says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3e/95/3e95b252-be33-4a87-871c-132f7c0e9555/hh2f79.jpg)

When asked how turning over rocks for hours to find slugs could possibly compare to the adrenaline of jumping out of planes, he replies: “How do you feel on Easter morning?” Every day was like Easter to him, he says. Same backyard, but new brightly colored objects hidden in new places.

Cobb has identified 789 species of nudibranchs in the 0.2 miles of the Mooloolah River ending in the open ocean. Part of the reason for this diversity is the tides: High tide sweeps nudibranchs and their larvae into the river, and many of them stick around. If hunting nudibranchs is like looking for colorful eggs on Easter Sunday, then the tides are the Easter bunny.

Along with being highly specialized animals, nudibranchs are also highly specialized eaters. Each species depends on one kind of prey, ranging from sponges and corals to anemones, jellyfish and even other nudibranchs. Jessica Goodheart is an assistant curator of malacology (the study of mollusks) at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. She studies how several species of nudibranchs steal stinging cells from their prey—anemones and jellyfish—to use in their own defense.

Nudibranchs eat using a radula, which is “kind of like a sharp, hard tongue,” says Goodheart. Watching a nudibranch eat isn’t, at first glance, all that different from watching a slug on a leaf. But if the nudibranch is feeding on a venomous animal, what is happening is actually very dramatic. Anemones and jellyfish have special cells called cnidocytes, which, when stimulated by touch or a change of chemicals in the water, launch tiny harpoon-like structures called nematocysts at enemies and prey.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b7/50/b7508e8d-2d97-4abe-acc4-9b758fcd2521/drgoodheart27.jpg)

As the nudibranch tries to grasp its prey, the prey fires its tiny harpoons at the nudibranch. But the nudibranch has a shield—something that stops the nematocysts from firing their venomous harpoons. “You see them pull back often, initially,” says Goodheart. But “eventually they’re able to latch on and continuously eat those tissues.” Scientists aren’t sure how, but one theory is that the power lies in the nudibranch’s slime.

The slugs graze on their living prey, and, as they digest their food, something incredible happens. The nudibranchs are able to turn the harpoons from their prey into ammunition they can use themselves. Unfired nematocysts pass through the nudibranch’s gut, where they are broken down into cells— and the cells are then broken down, releasing the nematocyst cells.

The nudibranch’s digestive system branches out into the tips of its body—the cerata. “There’s all of these branches of the digestive system, and the nematocysts move through those out into the very tips of these finger-like projections off the back of the animals,” she says. “It’s as if our intestines extended out into our hands and fingers.”

In those tips is a specialized sac, a cnidosac, where the undigested nematocysts are stored. When a threat approaches, the nudibranchs will orient their finger-like cerata toward the threat and then fire off the nematocysts they’ve stored.

Blue dragons, or Glaucus atlanticus, look as though they actually have hands and fingers. An inch long and electric blue, they sequester the stinging cells from the Portuguese man-of-war they eat, arming themselves against predators. To reach their prey, they swallow air bubbles so that they float to the surface of the ocean, where they lie on their backs. Their blue and gray coloring means that from below, they appear the same color as the sky, and from the sky, they blend into the water.

Goodheart designed an experiment that allowed her and her colleagues to see nematocysts moving through a nudibranch’s body in real time, something that hadn’t been done before. The hardest part was getting the nudibranch to stay still. Eventually she worked out that she could bribe it to stick to one spot by placing food on a glass plate under the microscope.

The slugs are like the video game character Kirby, from “Super Smash Bros.,” says Goodheart: When Kirby inhales objects or creatures, he gains their powers. And it’s not just venom.

Pteraeolidia ianthina, which looks like a Chinese dragon puppet, has long, wavy army green and electric purple cerata. It can photosynthesize using the photosynthetic cells from creatures it eats. After being swallowed by the slug, the algal cells continue to live in its digestive system, their chloroplasts photosynthesizing and producing energy, which is then used by the slug. Other nudibranch species do the same with zooxanthellae—single-celled organisms that live symbiotically on coral polyps.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/84/38/8438f163-37a4-41e0-9602-5ce5f3c7c50a/diversidoris_aurantionodulosaphoto_by_michael_awtenellia_sibogaephoto_by_michael_aw_awm9025_copy.jpg)

But their biggest superpower is surviving, says Kirkendale. “A soft body without a shell to hide in is a really big step to take. It’s brave, and they’ve done some tricky things in order to kind of be able to survive on a busy coral reef.”

It’s one of the things Pola loves most about nudibranchs. They appear “delicate and fragile,” she says. “They seem really defenseless but … they are some of the best-protected animals in the animal kingdom.”

As for Cobb, Pola appreciates that he wants to show that “science belongs to everyone and not just a few. And, more importantly, that collaborating is essential,” she says. “It’s not just his passion for diving, but sharing that information with everyone else, no matter what.”

Cobb and I are eating at a busy restaurant when he suggests an experiment. “Go over to that table and ask them if they know what a nudibranch is.” At the table are three adults with a young baby. I approach a little sheepishly and ask the question. It is zero for three, not counting the baby.

“It just kills me that so many people don’t know about them,” Cobb says. On the way back to the car after our meal, he stops seven more people: “Excuse me, can I ask you something? Do you know what a nudibranch is?” Met with furrowed brows, noes and shakes of the head, he opens his jacket like a flasher to show off his T-shirt: “They’re these things! Sea slugs!”

We are almost at the car when he approaches another young family, a man, woman and toddler. “Excuse me, do you know what—”

“Nudibranchs!” the man says before Cobb finishes.

“You know what they are?” Cobb asks.

“Nah, I heard you telling the guys next to us and I said, ‘He’s not going to get me.’”

But even if this bystander doesn’t know anything about nudibranchs, it becomes clear after chatting for a while that he knows who Cobb is. “Oh, so you’re the one always diving at Balsa Park,” he says.

Cobb says he’s been diving an average of four hours, twice a week, every week of the year for the past 21 years. That means he has spent about a year of his life underwater. When I tell him this over text he replies instantly: “Not enough!!”

We meet for a dive at 7 on a Sunday morning. Joining us are several people Cobb has turned into nudibranch enthusiasts. As they suck themselves into suits, they psych each other out about the cold (the air was 55 degrees). David Parker’s lips usually turn blue, they say. Parker works in telecommunications but got hooked on nudibranch hunting and photography after meeting Cobb on a nudibranch dive he was running. Fran Roberts and Nevar Fourie, a South African couple who are coders by day and divers by weekend, are so determined to avoid the cold that they have bought dry suits and are currently applying the several complicated layers to their bodies.

As Sheryl Wright, a high school English teacher, shows me the flippers Cobb has sliced into a sharp, fork-like shape to make moving along the riverbed easier, I snap the ankles of my rented wetsuit over booties, shove my head into a hood and tuck my sleeve into the gloves Cobb has lent me. After a glance at the park, with its carefree teenage surfers and cozy, tired parents with their cozy, sleepy newborns, I descend.

At 68 degrees Fahrenheit, the water is warmer than the air above it, and as we sink ten feet to the bottom of the river, I enjoy the calm and quiet. Then I look back: Behind me is Cobb’s small fleet of divers, furiously turning over rocks.

When Cobb spots a nudibranch underwater, he makes bunny ears with his fingers. (When he knows I’ve seen it, he pumps his fists.) The first one we see is the species named after Cobb, Murphydoris cobbi. It is tiny, barely bigger than a grain of rice, and shaped like a rabbit molded from a fleck of mochi: I can just—just—make out the rhinophores. Next we float over Tenellia sp. 24, shaped like the head of a miniature white asparagus, and sliding along the sandy bottom. Then Cobb makes a sort of honking sound and points out a mating pair of Murphydoris cobbi, attached head to toe.

Nudibranch hunters are the birdwatchers of the sea: They move slowly through their hunting ground and are excited by the smallest creatures. You get the feeling that were a whale to swim over us, blocking out the sun, they’d offer it a short, polite glance and get back to looking at nudibranchs.

We continue and soon see several larger slugs, Tenellia sibogae, an inch or so long, bright purple and orange, with tendrils like a sea anemone’s: a feather boa for a shrimp. As Cobb makes his way slowly along the floor of the river, he turns over stones or waves the water against larger rocks to blow away what looks like sea dust. He delicately brushes back fragile underwater plants and scans the floor or rock with his face an inch away from it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/e4/31e41c26-e838-4d19-b73b-f2ab3b812e23/diversidoris_aurantionodulosaphoto_by_michael_aw_awm9074_copy.jpg)

Then Cobb points out a long, frilly yellow ribbon of something, dangling off a rock: nudibranch eggs. Nudibranchs are hermaphrodites. They have both male and female reproductive organs and can act as both at the same time. They can’t fertilize themselves but will exchange sperm with a mate. Some dorids have penises in their necks and will mate top to tail with others, inseminating each other simultaneously. Chromodoris reticulata, a raspberry-colored slug, has a disposable penis, which it can regrow—and use—within 24 hours.

Each nudibranch, after its roll in the sea sponge, will then lay egg masses: orange, yellow, blue or pink spirals, some containing millions of eggs.

The larvae that hatch from these eggs will be transparent, with shells that are transparent, too, making them harder for predators to spot. They’ll float along among plankton until one day they cast off their shells and undergo a metamorphosis. Like an office worker changing from a gray suit into drag, they grow new, fabulous tissues.

This stage is called “settling,” and working out what makes the nudibranchs decide to settle is one of the biggest challenges of breeding or “culturing” them in laboratories, Goodheart explains.

“We don’t know what cues they use, like if there’s certain chemical cues or anything that they use to settle. And so often, you can’t keep a full life cycle.” She uses Berghia stephanieae, which can be cultured in a lab. She described the species as “bland”—for a nudibranch: translucent orange with white spots along its body, and iridescent bluish cerata.

It is almost easier to believe that Pokémon are real than it is to believe that nudibranchs are. They’re just too weird, too brightly colored and rabbit-shaped—too adorable to exist. At night, Parker says, he and Cobb dive with an ultraviolet lamp, under which the nudibranchs glow in even weirder ways.

Toward the end of the dive, I turn a rock over and find a large slug-like creature. It is deep purple, with a frilly orange and lilac border, which it waves vigorously. I sign bunny ears at Cobb. But this is no nudibranch: It is a flatworm pretending to be a nudibranch so that predators will mistake it for something venomous. As we watch, two rhinophores appear to poke out from its body: The worm has curled two small sections of its wavy edge into two very thin waves, imitating the bunny ears.

Nudibranchs have such good defense mechanisms—are so good at surviving, as Kirkendale put it—that other soft-bodied animals on the reef have evolved to copy them. She has seen sea cucumbers that have evolved to have the same coloration as their local nudibranchs.

But one threat nudibranchs are not prepared for is ocean acidification, which can stop larvae from forming their shells, which then stops them from being able to disperse. For outside observers, though, nudibranchs make good indicator species when it comes to climate change: They’re brightly colored, Goodheart says, so it’s easy to track their movements. “It’s obvious when they’re sort of entering or leaving an area,” she says. “And that can be really good for trying to understand the impact of temperature changes on an environment.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/24/86/2486d44d-8814-4be3-a4cc-42437b18ef00/dendrodoris_denisoniphoto_by_michael_aw_awm9307_copy.jpg)

Goodheart has a hunch that nudibranchs’ ability to ingest and use the organelles—parts of a cell—of another organism may have implications for medicine. Researchers are trying to work out how to use organelles like mitochondria and lysosomes to deliver drugs. By studying the mechanisms and genes that let nudibranchs process and use nematocysts from other creatures, Goodheart hopes to advance drug research in humans.

Then again, nudibranchs needn’t be good for anything. “Simply getting to know them, knowing that they exist, where and how they live, and what they are, already seems wonderful to me,” says Pola.

Over the course of our two-hour dive we see 24 nudibranch species and a total of about 200 individuals (a slow morning for Cobb, who once saw 1,000 individuals in five hours). Afterward, as the divers devour bowls of fries, and plates of eggs and toast, they discuss their helpless love of slugs.

“It’s like a disease,” Roberts says.

Wright agrees. “Now I infect other people.”

“It’s a thing that spreads,” Parker says.

“We tried not to become nudibranch nerds,” Fourie says, turning to me.

Roberts jumps in. “But after so many times of saying, ‘It’s that one with the stripes, and yellow,’ you decide to just learn their names.”

Not only had they learned their names, they’d given at least one individual nudibranch a name of its own—a Ceratosoma tenue they’d seen on multiple dives and recognized because it was missing a rhinophore and had a big scar running down its side.

“We named him Scarface,” says Wright, and picks up her phone so I can say hello to her little friend: She’d set the slug as her background.

:focal(1728x1053:1729x1054)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/10/e9/10e92871-2646-4dfc-87e2-20ea31a0203e/goniobranchus_sp_photo_by_michael_aw_awm9156_copy.jpg)