The Early History of Autism in America

A surprising new historical analysis suggests that a pioneering doctor was examining people with autism before the Civil War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/83/6d8354b7-835d-45c0-ae17-fb4ae66cf84c/janfeb2016_n05_autism.jpg)

Billy was 59 years old that spring or summer of 1846, when a well-dressed man from Boston rode into his Massachusetts village on horseback, and began measuring and testing him in all sorts of ways. The visitor, as we imagine the scene, placed phrenologist’s calipers on his skull, ran a tape measure around his chest and asked many questions relating to Billy’s odder behaviors. It was those behaviors that had prompted this encounter. In the parlance of the mid-19th century, Billy was an “idiot,” a label that doctors and educators used not with malice but with reference to a concept that owned a place in the medical dictionaries and encompassed what most of us today call, with more deliberate sensitivity, intellectual disability.

Billy’s name (but not the village he lived in) was on a list of the commonwealth’s known “idiots,” hundreds of whom would be visited that year. A few months earlier, the legislature had appointed a three-man commission to conduct, in effect, a census of such individuals. In Billy’s case, however, the man who examined him soon realized that no commonly accepted definition of intellectual impairment quite fit this particular subject. Although Billy was clearly not “normal,” and was considered by his family and neighbors to be intellectually incapacitated, in some ways he demonstrated solid, if not superior, cognition. His ability to use spoken language was severely limited, but he had perfect musical pitch and knew more than 200 tunes. Billy was not the only person whose combination of skills and strengths puzzled the examiners. As the leader of the commission would acknowledge, there were “a great many cases” seen in the course of the survey about which it was “difficult to say whether...the person should be called an idiot.”

But what diagnosis might have fit better? If Billy were alive today, we think his disability, and that of others documented then in Massachusetts, would likely be diagnosed as autism. True, the actual word “autism” did not exist in their time, so neither, of course, did the diagnosis. But that does not mean the world was empty of people whose behaviors would strike us, in 2016, as highly suggestive of autistic minds.

There are no known biological markers for autism. Its diagnosis has always been a matter of experts closely watching an individual, and then matching what that person says and does against established criteria. Finding it in the past requires finding a witness, also from the past, who was good at observing behaviors and writing down what he saw.

Like that man on the horse, whose devotion to hard data, fortunately for detectives of autism history, was far ahead of his time.

**********

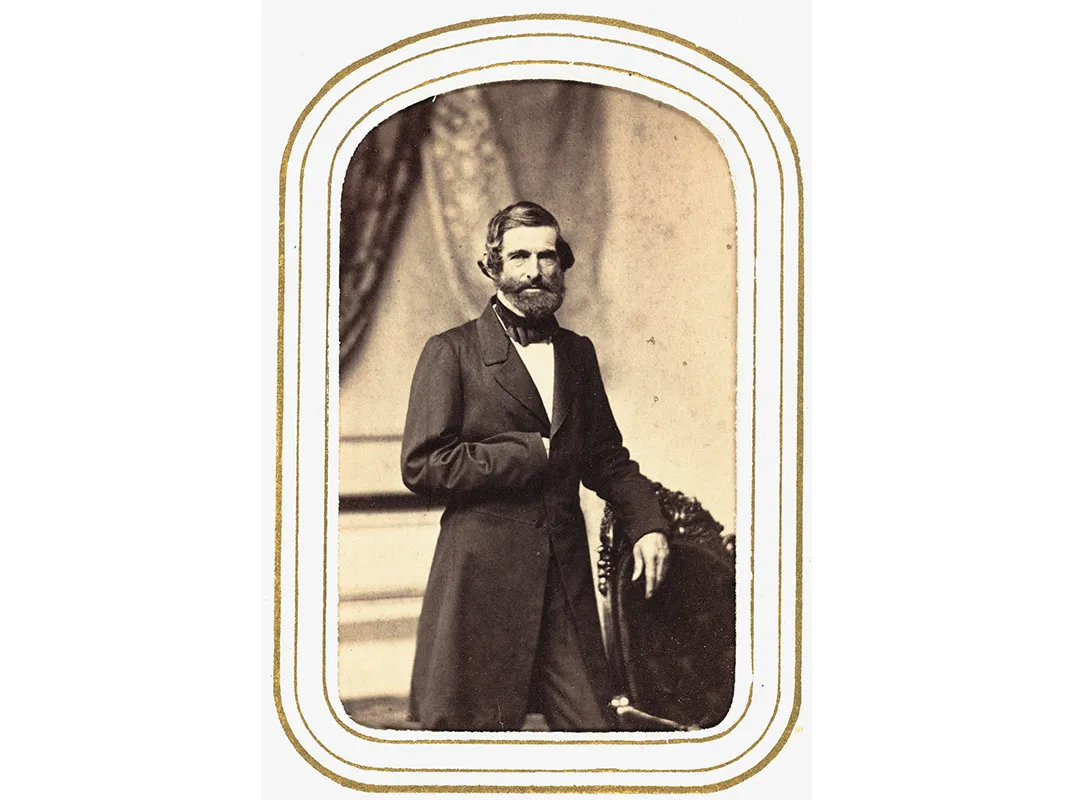

Samuel Gridley Howe, born into a well-to-do Boston family in 1801, was an adventurer, a medical doctor, a visionary educator and a moral scourge. He was also half of what today would be called a power couple. He and his New York-born wife, Julia Ward Howe, operated at the Brahmin level of Boston society, well-connected, well-traveled and with a shared commitment to the anti-slavery cause, which perhaps helped bind them together through their often stormy marriage. Samuel secretly raised funds for John Brown’s violent guerrilla campaign against slavery, and Julia, after visiting Abraham Lincoln at the White House in November of 1861, composed a set of verses whose original intent was to inflame a merciless passion for crushing the Confederacy. Today, with a few word changes, her “Battle Hymn of the Republic” is an American standard, struck up at high-school graduations and when presidents are buried.

Her husband’s most enduring achievement, however, is the 38-acre Perkins School for the Blind, in Watertown, Massachusetts—a storied institution that opened in 1832. Howe was the school’s first and longtime director, and lead designer of its groundbreaking curriculum. His radical idea, which he personally imported from Europe, was that people who are blind can and should be educated. Howe believed in the improvability of people, including those whose physical impairments most of society regarded as divine retribution for sins that they, or their parents, had committed. At the time, few others were interested in sending children who were blind to school: They were regarded as a lost cause.

That Howe would emerge as a thundering advocate for teaching children who were disabled would have stunned those who knew him only in his mischievous younger years. As an undergraduate at Brown University, he kidnapped the university president’s horse, led the animal to the top of a campus building and, the story goes, left it there to be found the next morning. After being caught throwing a stone through a tutor’s window and putting ashes in the man’s bed, Howe was not expelled from Brown but “rusticated”—sent to a remote village to live with a pastor. Around the same time, his mother died; he returned to school a changed man. He graduated in 1821, picked up a medical degree at Harvard in 1824, and then embarked on a lifetime of high-minded challenges, always as a champion of the underdog.

He headed for Greece first, and the front lines of a war, serving as a battlefield doctor on the side of the Greek revolutionaries rising up against Turkish rule. After that, he raised funds for Polish patriots in their struggle to throw off czarist domination. He spent a month of the winter of 1832 in jail in Prussia, where he had been holding clandestine rendezvous with Polish contacts.

Howe had a second reason for making that trip to Prussia. By then, on what seems like a whim, he had agreed to become the first director for the New England Asylum for the Blind. He’d gone to Prussia—and France and Belgium—to see how special education was done. He learned well. Within a decade and a half, Howe was a celebrated educator. His school, renamed after a financial benefactor, Thomas Handasyd Perkins, was a resounding success. Blind children were reading and writing, appreciating poetry, playing music and doing math. One student, Laura Bridgman, who was both deaf and blind, became a worldwide celebrity, especially after Charles Dickens published an account of spending time in her company in January of 1842. Dickens’ description of the girl’s “earnestness and warmth...touching to behold” helped advertise and validate Howe’s conviction that society should believe in the potential of disabled people. Some decades later, the Perkins School would enroll its most famous student—Helen Keller.

Emboldened by the school’s progress with blind students, Howe set out to prove that so-called idiots could learn and also merited a school to go to. For this he was publicly ridiculed—dismissed as a “Don Quixote.” But Howe had allies in the legislature, and in April of 1846, the body resolved to support a survey, led by him, of intellectually impaired citizens “to ascertain their number, and whether any thing can be done for their relief.”

**********

In November 2015, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a new estimate of the prevalence of autism in children ages 3 to 17. The figure, 1 in 45, is the highest ever announced by the CDC, up from 1 in 150 in 2007.

Though many news reports described the figure as an alarming jump in the number of people with the condition, in fact no study carried out to date can be said to tell us exactly how much autism exists in the population at any given moment. Instead, there are estimates with wide margins of uncertainty. The reasons are many: inconsistency in how the diagnosis is applied from one locale to another; disparities among different ethnic, racial and socioeconomic groups in the availability of diagnostic services; and greater autism awareness, which tends to drive rates higher in places where the condition is better recognized. Notably, the CDC’s 1-in-45 estimate is based not on direct observation of children, but on interviews with parents, who were asked whether a child in the family had been diagnosed with autism or any other developmental disability. Among the acknowledged limitations of the approach is that it cannot correct for errors or differences in how the diagnosis was made in the first place.

In addition, researchers have continually revised the operative definition of autism, generally in a direction that makes it easier to qualify for the label now than in the past. This has added to the impression that the true, underlying rate is increasing. It may well be that autism is on the rise. But it may also be that we are getting better at finding those people who merit the diagnosis and were once overlooked.

Still, the dominant narrative has been that real rates are going up, and the United States is in the midst of an autism “epidemic,” even though most experts see that as a highly debatable proposition. Moreover, the “epidemic” story has helped crystallize the notion that “something must have happened” in the near past to cause autism in the first place. Most famously, some activists blamed modern vaccines—a now discredited theory. Air and water pollution have also been posited. Such 20th-century factors accord with the history of autism as a diagnosis: The condition was not even named in the medical literature until the late 1930s.

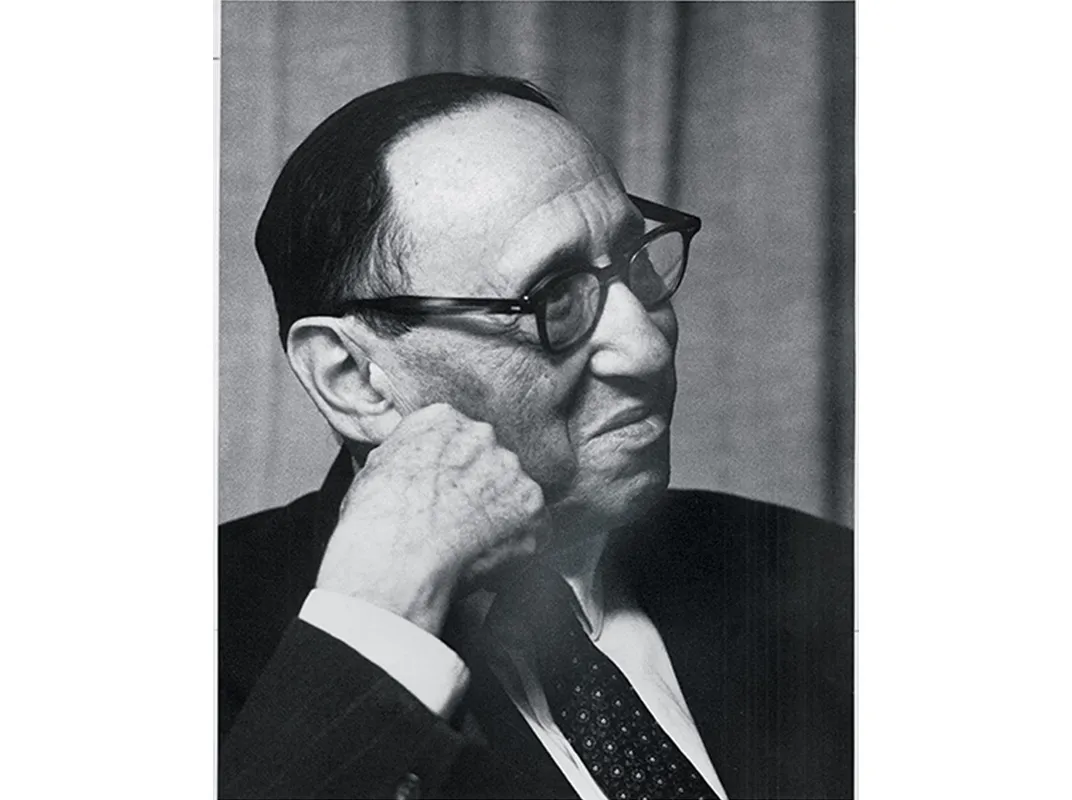

Yet even the man usually credited with first recognizing autism, a Baltimore-based child psychiatrist named Leo Kanner, doubted that the profound impairment in social relatedness he first reported seeing in 11 children in 1943 was, in fact, something new in human history. While a Viennese pediatrician named Hans Asperger described something similar, Kanner’s account was more influential. His contribution, he said, was not in spotting the disparate behavioral traits that constitute autism—strange use of language, a disconnectedness from human interaction and a rigid affinity for sameness, among others—but in seeing that the conventional diagnoses used to explain those behaviors (insanity, feeblemindedness, even deafness) were often mistaken, and in recognizing that the traits formed a distinctive pattern of their own. “I never discovered autism,” Kanner insisted late in his career. “It was there before.”

Looking back, scholars have found a small number of cases suggestive of autism. The best known is the Wild Boy of Aveyron, later given the name Victor, who walked naked out of a French forest in 1799, unspeaking and uncivilized, giving birth to fantastic tales of a child raised by wolves; in recent decades experts have tended to believe that Victor was born autistic and abandoned by his parents. The behavior of the so-called Holy Fools of Russia, who went about nearly naked in winter, seemingly oblivious to the cold, speaking strangely and appearing uninterested in normal human interaction, has also been reinterpreted as autistic. And today’s neurodiversity movement, which argues that autism is not essentially a disability, but, rather, a variant of human brain wiring that merits respect, and even celebration, has led to posthumous claims of autistic identity for the likes of Leonardo da Vinci, Isaac Newton and Thomas Jefferson.

As far as we can determine, we are the first to suggest the diagnosis for Howe’s numerous cases, who appear to constitute the earliest known collection of systematically observed people with probable autism in the United States. We came across them during the fourth year of research for our new book, In a Different Key: The Story of Autism, by which time our “radar” for autistic tendencies was fairly well-advanced. Granted, retrospective diagnosis of any sort of psychological state or developmental disability can never be anything but speculation. But Howe’s “Report Made to the Legislature of Massachusetts upon Idiocy,” which he presented in February of 1848, includes signals of classic autistic behavior so breathtakingly recognizable to anyone familiar with the condition’s manifestations that they cannot be ignored. Plus, his quantitative approach vouches for his credibility as an observer, despite the fact that he believed in phrenology, which purported to study the mind by mapping the cranium, long since relegated to the list of pseudosciences. Howe’s final report contained 45 pages of tabulated data, drawn from a sample of 574 people who were thoroughly examined by him or his colleagues in nearly 63 towns. The tables cover a wide range of measurements as well as intellectual and verbal capacities. Howe, extrapolating, estimated that Massachusetts had 1,200 “idiots.”

Billy was Number 27 in the survey. Across 44 columns of data, we learn that he was 5 feet 4 inches tall, his chest was 8.9 inches deep and his head was 7.8 inches in diameter front to back. At least one of his parents was an alcoholic, he had one near relative who was mentally ill or disabled, and Billy himself was given to masturbation. (Howe subscribed to the once commonly held view that masturbation was a cause of mental disability.) Billy was given a low “4” rating in the “Ability to Count” column (where the average was “10”). His “Skill in the Use of Language” was also below average, at “6.” But his “Sensibility to Musical Sounds” was on the high side, at “12.”

As much as Howe favored precise measurement, he was honest in admitting that his tables of data failed to capture essential aspects of Billy’s personality. Rather than gloss over the problem, Howe acknowledged that Billy’s musical gifts and other qualities made it difficult to label the young man as an “idiot.” A striking observation that reinforces the notion that Billy was autistic concerns his spoken language. Howe gave this account: “If he is told to go and milk the cows, he stands and repeats over the words, ‘Billy, go and milk the cows,’ for hours together, or until some one tells him something else, which he will repeat over in the same way.” And yet, Howe reported, Billy was capable of understanding nonverbal communication. “Put a pail in his hand,” he wrote, “and make the sign for milking, and give him a push, and he will go and fill the pail.”

Experts today refer to the tendency to repeat words or phrases as echolalia. It is listed in the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as one of the “stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech” that can contribute, in combination with other behaviors, to a diagnosis of autism.

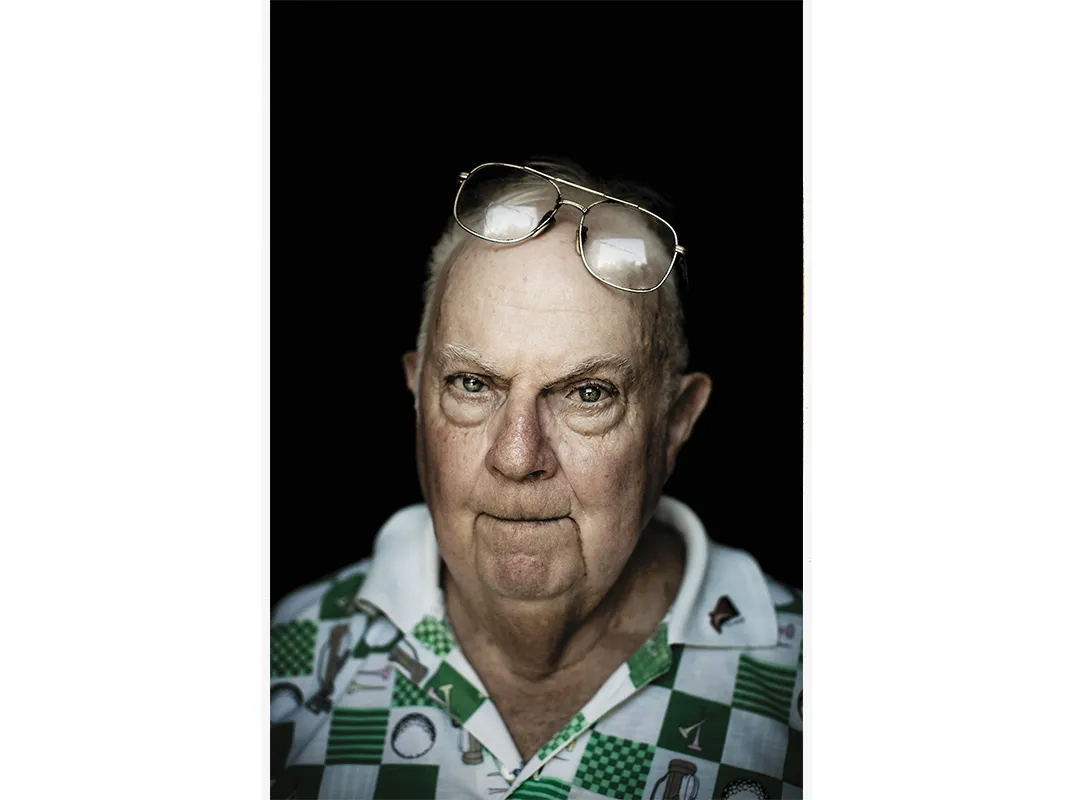

Echolalia does not necessarily persist for life. For example, we have spent time with the first child whom Leo Kanner cited in his groundbreaking 1943 paper, autism’s “Case 1,” Donald Triplett, now a healthy 82 years old. Donald can engage in conversational speech, but he had pronounced echolalic tendencies as a child, when he uttered random-seeming words and phrases such as “trumpet vine,” or “I could put a little comma,” or “Eat it or I won’t give you tomatoes.” It is fascinating that the young Donald demonstrated some other traits that made Billy stand out to Howe back in the 1840s. Like Billy, he had an unusual gift for remembering songs; as a toddler, Donald was singing complete Christmas carols after hearing them just once. Also like Billy, Donald had perfect pitch; when he belonged to a choir, the director relied on Donald to give his fellow choristers their starting note, in lieu of a pitch pipe.

It is often noted that no two people with autism ever have it in exactly the same way. While Billy was reported to be bad at counting, Donald was fascinated by numbers, and could multiply double- and triple-digit numbers in his head instantly and flawlessly.

Howe did discover that same talent for numbers among other people in his study population. One man, Case 360, “has the perception of combination of numbers in an extraordinary degree of activity,” Howe wrote. “Tell him your age, and ask him how many seconds it is, and he will tell you in a very few minutes.” Cases 175 and 192 also confounded Howe, as they were both able to count up to “20,000 and perform many simple arithmetical operations, with a great deal more facility than ordinary persons.”

Finally, Howe drew attention to a young man, Case 25: “This young man knows the name and sound of every letter, he can put the letters into words, the words into sentences and read off a page with correctness; but he would read over that page a thousand times, without getting the slightest idea of the meaning.”

That description is highly reminiscent of the modern idea that autism involves a tendency for “weak central coherence.” It is another way of saying that autistic people are better at processing parts of a pattern—while missing how the parts fit together in the pattern as a whole. (Donald’s mother remarked that he loved going to the movies as a boy, but always came home unaware that the flashing images were meant to add up to a story.)

To be sure, Howe’s cases do not prove there was a lot of autism in his day, or even any. But the concept of autism helps explain some of the cases that puzzled him. We showed Howe’s observations to Peter Gerhardt, chairman of the scientific council of the Organization for Autism Research. Absent some contradictory information, and invoking the precaution about evaluating people one had not met face to face, Gerhardt told us that “autism spectrum disorder would appear to be a far more accurate description” than intellectual disability for those individuals.

Howe may have been primed to spot “outlier” cases as a result of correspondence with a fellow physician named Samuel Woodward, head of a Massachusetts facility then known as the Worcester Lunatic Hospital. The year before Howe undertook his survey, he published a letter in the Boston Daily Advertiser, citing a report that Woodward had shared with him. Woodward described a group of children in his care who didn’t fit the usual categories. These “little patients have intelligent faces, well-formed bodies, good developments of the head, and active minds,” Howe wrote, citing Woodward: “Their movements are free, easy and graceful, many of them are sprightly, even handsome; they are generally restless, irritable and extremely mischievous, and are rarely able to speak.... No person familiar with these cases would be likely to mistake them for idiots.”

What would their diagnosis be if those children were seen by a neurologist today? James Trent, author of the superb 2012 Howe biography The Manliest Man, has suggested that this group of children in Worcester would be diagnosed with autism, much as we are suggesting that Howe’s cases were also candidates for the label.

**********

Howe was appalled by the horrifying conditions in which many “idiots” lived—crammed into almshouses, kept in cages, left to wander unwashed and uncared for. He demanded that society do better by this vulnerable group. When the community failed “to respect humanity in every form,” Howe wrote in a letter to a state legislator, it “suffers on account of it” and “suffers therefor [sic] in its moral character.”

Part of his agenda was to persuade the legislature to fund a school for the mentally disabled. He succeeded. After reading an interim report about his survey, lawmakers appropriated $2,500 for the purpose, which allowed Howe to take in ten mentally disabled students at Perkins. He proved, in short order, that they could indeed be educated. Based on that success, Howe founded a second school—the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded, subsequently renamed the Fernald State School, and then the Fernald Center. Unfortunately, in later decades, his innovative facility fell victim to the neglect that defined many similar institutions in the 20th century. More like warehouses than schools, these institutions confined people in overcrowded conditions, while delivering little that could be called education. Despite real efforts at reform in the last part of the 20th century, the center was finally closed for good in 2014.

**********

Howe had begun warning, in the years before his death in 1876, against the trend he saw taking shape, of states moving to segregate disabled people behind institutional walls in distant locations. Howe’s forward thinking had its limits, though. Even with his fervent anti-slavery views, he took the cultural superiority of the white race for granted. And his conviction that women deserved education was tempered by his adamant belief that a wife’s place—including that of his famously activist spouse—was in the home. This early progressive who believed in the perfectibility of people was himself “not a perfect man,” as Trent put it.

A primary goal of Howe’s pioneering mental health survey was to discover the root cause of intellectual disability. In that respect, of course, he failed. But conceding that “the whole subject of idiocy is new,” Howe expressed hope in 1848 that his data would be of use to future generations trying to understand mental disability. “Science,” he said, “has not yet thrown her certain light upon its remote, or even its proximate causes.”

A century and a half later, we’re in much the same position in regard to autism. Still not sure how good we are at gauging autism in the population—or even at defining its boundaries—we wait for science to illuminate the mystery of its origins. Howe’s careful humanitarian work strongly suggests that answers may yet be found in the undiscovered past.