Ebola Vaccine For Chimps Could Help Save Wild Populations

A trial of a chimp vaccine highlights debates over vaccinating wild populations and using chimps in medical research

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/48/6548439a-35fc-482b-8099-1a74472bfa7f/42-44663194.jpg)

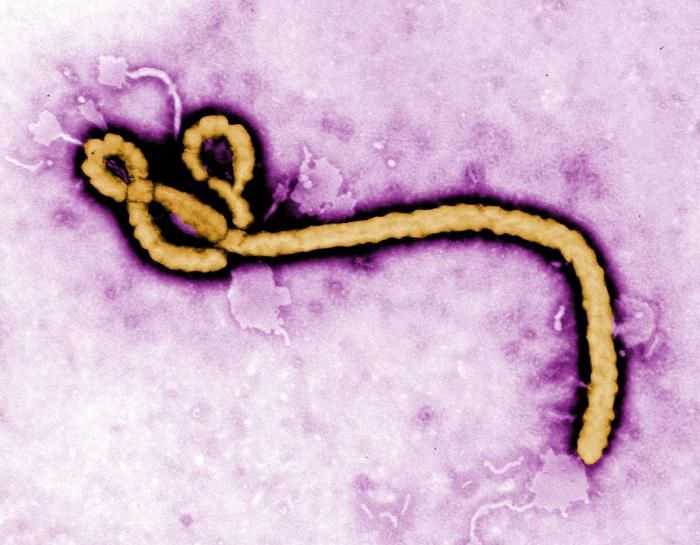

Ebola virus is a pretty scary disease for humans, but it’s equally scary for great apes. Since 1994, massive outbreaks in Africa have hit chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and killed an estimated third of the world’s gorillas (Gorilla sp.). For the endangered chimps and critically endangered gorillas, the problem now rivals poaching and habitat loss.

“Ebola virus has done an extraordinary amount of damage in gorilla and chimpanzee populations in Africa over the last 20 or 30 years. We’re talking tens of thousands of apes,” says Peter Walsh, a primate ecologist at the University of Cambridge. Walsh and his colleagues think they have a solution: develop a vaccine that works in captive chimps to save those in the wild. The results of their successful vaccine trial were published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The prevailing theory is that fruit bats carry the virus without symptoms and somehow give it to apes. But where the virus goes between outbreaks is unknown as is how chimps and gorillas get it. The only way scientists have known about outbreaks is through ape carcasses that turn up and documented population losses in areas where a known Ebola outbreak has occurred. In some of these outbreaks, large colonies of apes suddenly disappear—an outbreak in Gabon and the Congo killed an estimated 5000 gorillas from 2002 to 2003.

With so many unknowns, the most realistic—and affordable—solution to stemming Ebola’s spread in great apes may be vaccination. Although a lot of work has focused on developing an Ebola vaccine for humans, Walsh thinks that some vaccines that didn’t make the cut for humans could work for chimps.

The most affective vaccines contain live versions of the replicating virus itself. Live vaccines come with a higher risk of infecting the animal and a real danger of spreading the disease. However, a virus-like protein (VLP) vaccine just contains a piece of the protein coating that envelops the virus. It trains immune systems to recognize the protein and produce the requisite antibodies to fight the virus without the risk of infecting the animal.

“Later on if you’re actually infected your immune system says, ‘Aha I know what that is,’ and it kills it,” says Walsh.

The team chose a VLP vaccine that had protected captive macaque monkeys and mice against the dangerous Zaire strain of Ebola. They then worked with six research chimpanzees at the New Iberia Research Center in Louisiana. They administered the vaccine to each chimp in three doses over 56 days and tested the animal’s blood for specific antibodies and virus-fighting T-cells after each dose. The chimps showed no signs of symptoms, but they did produce a substantial immune response.

Next, the researchers injected groups of mice—one with saline solution and one with chimp blood samples flush with Ebola antibodies and T-cells. Then, they gave the mice Ebola. Mice injected with the blood had a much higher chance of survival, while those injected with the saline solution all died from the disease.

The team’s larger motive is to prove that the technology works before they conduct field trials in Africa. To inoculate a wild chimp or gorilla you’d need to deliver the vaccine via dart three times, and that’s where things get complicated.

“Any vaccine that would require three immunizations—that’s going to be a logistical nightmare,” says Tom Geisbert, a vaccine expert at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. Deep in the forests of central Africa darting the same animal three times seems like a long shot.

It’s also unclear how long that immunity would last, too, though Geisbert suspects no more than a year. In contrast, the riskier live vaccine typically only requires one dose to protect the individual for a decade in some cases and would confer longer immunity. And if the one dose—whether of live or VLP vaccine—could be taken orally, that would be even better,

Improvements in vaccine technology might make oral vaccines a reality in the next decade or two. Nonetheless, Walsh is pushing for a short-term solution because wild apes may not have decades.

Efforts to develop ape vaccines are embroiled in a larger debate over the use and treatment of chimpanzees in research laboratories, including the New Iberia facility where this trial was conducted. Last summer, the National Institutes of Health announced plans to retire over 300 of its 360 research chimpanzees, partly because some researchers think that chimps are now largely unnecessary in human biomedical research thanks to better animal models for testing medicines. Animal rights groups also argue that the caged conditions the animals are kept in during trials are unsanitary and inhumane.

The soon-to-be-retired research chimpanzees are used to test human vaccines. But now, “Animal welfare is trumping the survival of these species,” Walsh says. The authors argue that perhaps we owe it to chimps to maintain humanely housed captive populations devoted to conservation research.

Others see the research populations as unnecessary. “I don’t think that’s a justification for keeping chimpanzees in that setting, that in and of itself. There are other animals that can be utilized as proxies,” says Karen Terio, a veterinary pathologist at the University of Illinois in Urbana who was not affiliated with the study. Macaques, other monkey species, and more sophisticated mouse models could adequately demonstrate the safety of the vaccine for wild ape population use, she argues. Although some groups still feel the use of other animals is inhumane, these animals are commonly viewed as not capable of the same psychological trauma that testing may have on ape subjects.

At the very least, the trial raises awareness that poaching and habitat destruction aren’t the only troubles that chimps face. Ebola also isn’t the only disease that infects great apes; simian immuno-deficiency virus (SIV or the ape version of HIV) and malaria are two others that threaten these endangered wild populations. Humans can transmit other viruses to apes, as well. Ironically, many apes living in protected or sanctuary areas catch respiratory viruses from humans—conservationists, researchers, tourists even.

Walsh hopes that the trial opens the door for vaccinating chimps and other apes against these other pathogens too. “To conserve them, we’re killing them,” says Walsh. “It becomes more difficult to justify not doing it [vaccinating them] on emotional grounds.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)