Eight Fun Facts About Black Widows

The venomous spiders are nimble, secretive and dangerous

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/0f/460f898d-d49c-44d1-ae58-f72415f0063e/banner-cropped.jpg)

According to a comic published in 2019, Avengers founding member Natasha Romanoff earns the codename Black Widow because she works “like the deadliest of spiders, easily escaping notice until it is far too late.” Black widows have a notorious place in the popular imagination as frighteningly inconspicuous, highly venomous creatures that can kill a person with one bite. But the little arachnid’s reputation has been blown out of proportion. To help you better separate fact from fiction, here are eight amazing details about black widow spiders.

They are not the world’s deadliest spider

Contrary to the Marvel comic’s claim, black widows are far from the deadliest spider on Earth. But they do have a more intimidating name than the world’s actual most-venomous spiders, Australia’s funnel-web spiders. The Australian redback spider, a close relative of American black widows, is another contender because its venom is more potent and its bites are more common than funnel-webs.

Black widows are the most venomous spider in North America. Their venom is about 15 times stronger than rattlesnake venom, and uses a chemical called alpha-latrotoxin to overwhelm nerve cells and cause immense pain. When the alpha-latrotoxin reaches a person’s nerve cell, the nerve dumps all of its signaling chemicals at once, overwhelming its neighbors. In addition to pain, the a bite can cause swelling around the wound, severe cramping, sweating and chills.

But spiders are much smaller than snakes and don’t release much venom at once, so black widow bites only present high risk to young children and elderly people.

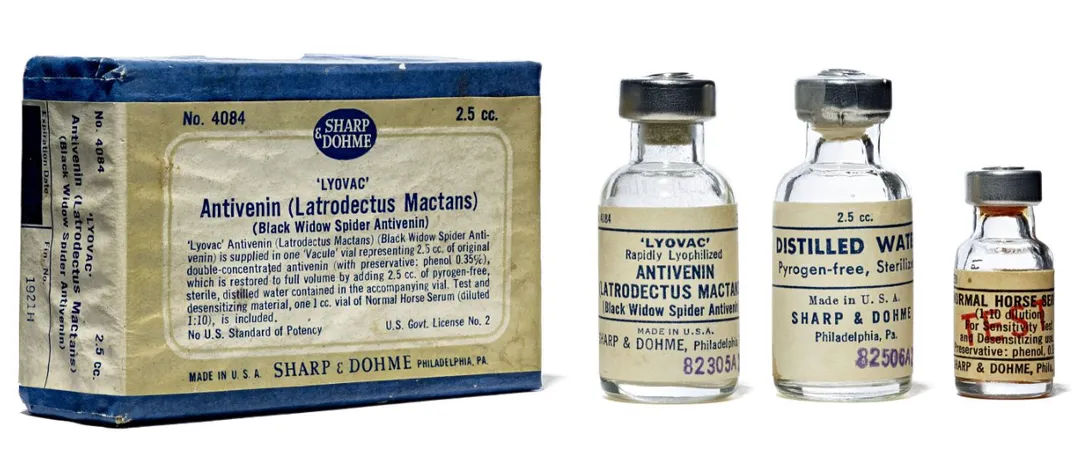

Antivenom exists for bite victims

Roughly 2,500 people go to poison control centers with black widow bites each year to shorten the symptoms with the help of antivenom. Antivenom isn’t prescribed in every case—usually just if the patient is at high risk, has trouble breathing, has high blood pressure or is pregnant.

Antivenom to black widow bites was first manufactured in the 1930s. To make the antivenom, pharmaceutical producers expose horses to small amounts of black widow venom. The horse’s immune system reacts by creating antibodies that target chemicals in the venom. Pharmaceutical producers draw blood with those antibodies and purify them to be used in victims. Those antibodies neutralize venom by flagging a person’s immune system to destroy the pain-inducing chemicals.

Not one, but many species exist

Three North American spider species go by the common name “black widow.” They are the western species, Latrodectus hesperus; the northern species, Latrodectus variolus; and the southern species, Latrodectus mactans. Female black widows can reach about one and a half inches long. They are shiny and black, with bright red hourglass-shaped markings on their abdomens. Males are half the size, lighter-colored and have red or pink spots.

As their names suggest, the southern black widow lives across the southern United States, the western along the west coast and in the desert, and the northern black widow can be found in the upper contiguous U.S. and southern Canada.

Black widows share their taxonomic genus with a wild array of 30 other spiders found around the world. The newest addition to the Latrodectus genus, the Phinda button spider, was discovered in 2019 in South Africa, and it lays bright purple eggs.

The young spiders are cannibals

Marvel’s “Black Widow” was trained to kill from a young age, and young black widow spiders have a penchant for violence, too. Research published in 2016 in the journal Animal Behavior showed that when black widow spiderlings hatch together at many different sizes, the largest among them quickly consume their smallest siblings. In trials when the spiderlings hatched at about the same size, they didn’t jump to cannibalism right away.

"The last thing a mother wants is out of her 300 babies, to have one giant one and 299 dead ones," said spider expert Jonathan Pruitt of the University of California at Santa Barbara to the Washington Post’s Joshua Rapp Learn in 2016. "It really suggests that females have been able to provision their eggs very precisely… so their development is in lockstep."

Sexual cannibalism is surprisingly rare

Black widows earned their name because scientists witnessed the females eat their mates after copulation. But research has shown that in a related species, redback spiders, females only cannibalize their mates about two percent of the time, so experts suspect that American black widows have similar rates of cannibalism in the wild.

The widows’ cannibalistic behavior was first observed in the lab, where males had nowhere to run away from their larger, hungrier counterparts. But in the spiders’ natural habitats, males have the opportunity to make an escape.

Male black widows also have strategies to avoid riskier sexual encounters in the first place; for instance, research suggests they can tell whether or not a female is hungry by her pheromones, so they can avoid potential mates who seem a bit peckish.

And some related species take an aggressive approach. Brown widow and redback spiders sometimes use a process called “traumatic insemination.” If a male happens upon a juvenile female that has developed only its internal plumbing, the male can pierce a hole in the female’s shell with its fangs and mate. The practice didn’t seem to cause permanent harm to the female spiders, and it gave the males a chance to pass on their genes without getting eaten, and search for another mate down the line.

Tiny slits are used for “Spidey” senses

All of the spiders in the Latrodectus genus have a few things in common: curved feet covered in bristles, earning them the name comb-footed spiders, and messy, irregular nests of silk called tangle webs. Western black widows take two different strategies to build their webs depending on how well-fed they are: starving spiders build more sticky threads, which snag prey, and healthy spiders invest more time in supporting threads, which may stop them from overeating.

The spiders rely on strands of silk in their tangle webs as extensions of their own senses. Thousands of organs called slit sensilla, which look like cracks in the exoskeleton and are especially common on their leg joints, feel vibrations in the silk. By changing its posture, a spider changes the shape of the slit sensilla, so a black widow can tune its senses to certain frequencies of vibrations coming down its web.

Coloring sends a message

The red hourglass on a female black widow’s abdomen sends a clear message: Danger. But humans aren’t the only ones on the lookout for a black widow’s signals. The insects hunted by black widows want to avoid falling into their jaws. Birds and wasps, which generally avoid red critters since it’s a common sign of venom, prey on spiders. (The black widow’s venom doesn’t pack a punch when it’s the one getting eaten.) So as the black widows evolved, they needed to strike a balance between hiding from prey and warning predators off.

Colorado College spider researcher Nicholas Brandley conducted experiments with 3D-printed widows showed that bright red spots protected the fake spiders from bird attacks, he told Smithsonian magazine in 2016. Unadorned plastic spiders were attacked three times more often than the red-spotted ones. In another experiment, a live black widow with many red spots tended to build its web higher up in terrariums than its less-colorful counterpart. The extra spots may give it more protection from predators up high and lurking below.

Climate change is expanding their range

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/2a/0d2a1019-93fa-4c59-a253-4c390ea2a20d/climateexpand-resized.png)

Black widows are most common in the warm environments of the southern and southwestern United States. While they tend to disappear when winter weather arrives, they don’t actually get killed when the temperature starts to drop. Instead, black widows find a protected area and go into a dormant state called overwintering. In spring, they emerge, and the tricky business of mating begins.

Black widows are rare at the northernmost stretches of their range, but climate change may soon change that. Northern black widows today live about 31 miles further into Canada than they did in the 1960s.