Endangered Ocean Creatures Beyond the Cute and Cuddly

Marine species threatened with extinction aren’t just whales, seals and turtles—they include fish, corals, mollusks, birds, and a lone seagrass

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/fa/b6fac75f-1549-4dd3-bd30-668e5431bd50/staghorn-coral.jpg)

Our oceans are taking a beating from overfishing, pollution, acidification and warming, putting at risk the many creatures who make their home in seawater. But when most people think of struggling ocean species, the first animals that come to mind are probably whales, seals or sea turtles.

Sure, many of these large (and adorable) animals play an important part in the marine ecosystem and are threatened with extinction due to human activities, but in fact, of the 94 marine species listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), only 45 are marine mammals and sea turtles. As such, these don’t paint the whole picture of what happens under the sea. What about the remaining 49 that form a myriad of other important parts of the underwater web?

These less charismatic members of the list include corals, sea birds, mollusks and, of course, fish. They fall under two categories: endangered or threatened. According to NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (pdf), one of the groups responsible for implementing the ESA, a species is considered endangered if it faces imminent extinction, and and a species is considered threatened if it is likely to become endangered in the future. A cross section of these less-known members of the ESA’s list are described in detail below.

1. Staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis), pictured above, is one of two species of coral listed as threatened under the ESA, although both are under review for reclassification to endangered. A very important reef-building coral in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, it primarily reproduces through asexual fragmentation. This means that its branches break off and reattach to a substrate on the ocean bottom where they grow into new colonies.

While this is a great recovery method when only part of a colony is damaged, it doesn’t work so well when most or all of the colony is killed—which often is the result from disturbances afflicting these corals. Since the 1980s, staghorn coral populations have steeply declined due to outbreaks of coral disease, increased sedimentation, bleaching and damage from hurricanes. Although only two coral species are currently on the ESA list, 66 additional coral species have been proposed for listing and are currently under review.

2. The white abalone (Haliotis sorenseni), a large sea snail that can grow to ten inches long, was the first marine invertebrate to be listed under the ESA but its population hasn’t recovered. The commercial fishery for white abalone collapsed three decades ago because, being spawners that jet their eggs and sperm into the water for fertilization with the hope that the two will collide, the animals depend on a large enough population of males and females being in close proximity to one another to reproduce successfully.

Less than 0.1% of its pre-fished population survives today, and research published in 2012 showed that it has continued to decline since its ESA listing more than a decade ago. The researchers recommended human intervention, and aquaculture efforts have begun in an effort to save the species.

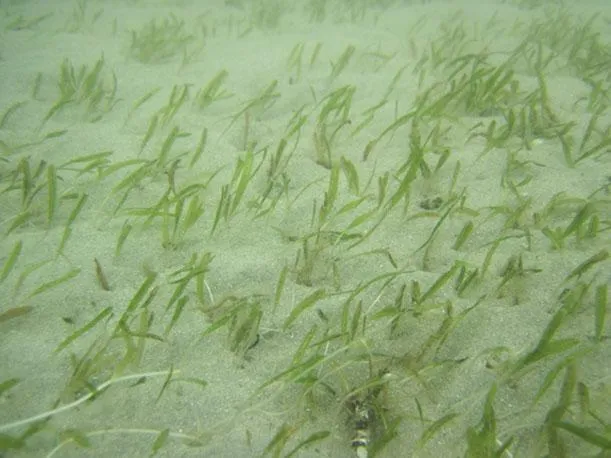

3. Johnson’s seagrass (Halophila johnsonii), the lone marine plant species listed, is classified as threatened and makes coastal habitats and nurseries for fish and provides a food source for the also-endangered West Indian manatees and green sea turtles. However, its most important role may be long-term ocean carbon storage, known as blue carbon: seagrass beds can store more carbon than the world’s forests per hectare.

The main threats to Johnson’s seagrass are nutrient and sediment pollution, and damage from boating, dredging and storms. Its plight is aggravated by its tiny geographic range–it is only found on the southeast coast of Florida. The species may have more trouble recovering than other seagrass species because it seems to only reproduce asexually–while other seagrasses can reproduce like land plants, by producing a flower that is then fertilized by clumps of pollen released underwater, the Johnson’s seagrass relies on the sometimes slow process of new stems sprouting from the buried root systems of individual plants.

4. The short-tailed albatross (Phoebastria albatrus) differs from some of its neighbors on the ESA list in that an extra layer of uncertainty is added to the mix: During breeding season, they nest on islands near Japan, but after breeding season ends, they spread their wings and fly to the U.S. In the late 19th century, the beautiful birds are thought to have been fairly common from coastal California up through Alaska. But in the 1940s, their population dropped from the tens of millions to such a small number that they were thought to be extinct. Their incredible decline was due to hunters collecting their feathers, compounded by volcanic damage to their breeding islands in the 1930s.

Today they are doing better, with over 2,000 birds counted in 2008, but only a few islands remain as nesting sites and they continue to be caught as bycatch, meaning that they are often mistakenly hooked by longline fishing gear.

5. Salmon are a familiar fish frequently seen on the menu. But not all species are doing well enough to be served on our plates. Salmon split their time between freshwater (where they are born and later spawn) and the ocean (where they spend their time in between). Historically, Atlantic salmon in the U.S. were found in most major rivers on the Atlantic coast north of the Hudson, which flows through New York State. But damming, pollution and overfishing have pushed the species to a point where they are now only found along a small section of the Maine coast. Twenty-eight populations of Pacific salmon are also listed as threatened or endangered. Efforts on both coasts are underway to rebuild populations through habitat restoration, pollution reduction and aquaculture.

The five organisms listed here are just a few of the marine species on the ESA’s list. In fact, scientists expect that as they learn more about the oceans, they will reveal threats to more critters and plants.

“The charismatic marine species, like large whales sea turtles…were the first to captivate us and pique our curiosity to look under the waves,” says Jonathan Shannon, from the NOAA Fisheries Office of Protected Species Resources. “While we are learning more about the ocean and how it works every day, we still have much to learn about the different species in the ocean and the health of their populations.”

Learn more about the ocean from the Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal.