Enjoy Face Time with Seven of Earth’s 3 to 5 Million Mite Species

A Smithsonian collection of some one million species of mites is receiving its up close and personal

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/09/370962ef-c107-4701-89e6-8d7631bc9645/sem-purplemite.jpg)

Because there is no polite way to ask a mite to sit still for its portrait, Gary Bauchan often gives his tiny subjects a shot of liquid nitrogen instead. At -321 degrees Fahrenheit (-196 Celsius) these fidgety eight-legged arachnids are flash frozen. Bauchan then zooms in for a close-up.

Many of the mite species imaged with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s state-of-the-art scanning electron microscope have been on Earth for millions of years. In most instances Bauchan and USDA Entomologist Ron Ochoa are the very first humans to ever see the grotesque yet remarkable features of their bodies and faces.

Mites are everywhere, Ochoa points out. Almost every species of beetle, bird, snake, plant and ant (and everything else, it seems) has between one and four associated species of mites. Mites live in soil, in caves, on us, in the treetops, and even in the water. They’re some of the toughest pests to manage on some of the most economically important crops. Sixty thousand mite species are known to science yet experts estimate the world is crawling with as many as three to five million species.

In his Beltsville, Maryland, research facility, Ochoa oversees a collection of some one-million mite specimens representing 10,000 species. Mounted on glass slides, the mite collection is owned and maintained by the department of entomology of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Here, Ochoa and Bauchan share images of a few of the many new mites that are being discovered each year. “We want to take close-up shots of the faces of these mites,” Ochoa says. “The way you see your mother, your father, your family and your friends and say hello is the way we want to say hello to the mites, face to face.”

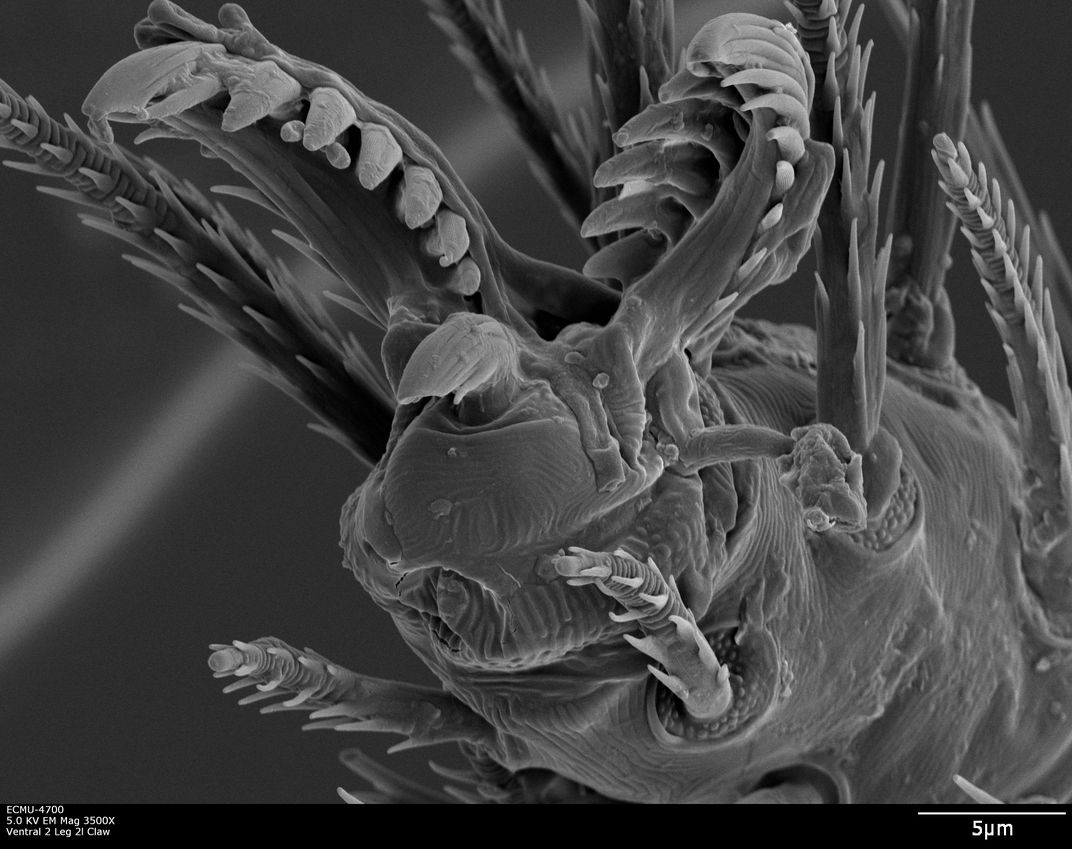

Family Anystidae (unnamed species)

Family Anystidae (unnamed species) Some members of this mite family are among the fastest animals in the world relative to their size. Also called “whirligig mites” for their peculiar style of running, one of the more familiar members of this family include the itch-inducing chigger. This mite—so new to science that it is still unclassified at the species and genus level—is a vivid red to orange predator with large, bristly bunny-ear shaped claws that it uses to grip the surface of leaves while searching for prey. “It’s like a super-Nike shoe for running, but this mite invented them millions of years before humans,” Ochoa says. Ochoa and Cal Welbourn, a mite expert at the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, are working to understand the biology of this mite family of mites with hope that one day it may help control mite pests of tree-fruit crops.

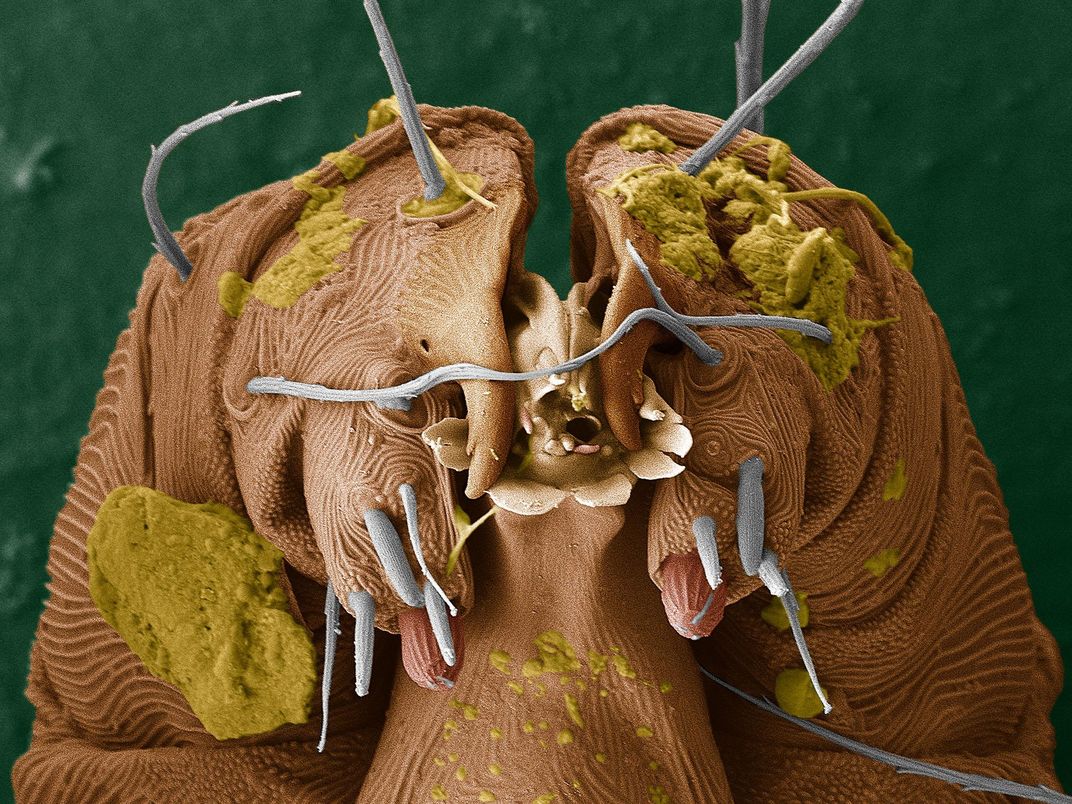

Michaelia neotropica

Michaelia neotropica This fine mustachioed fellow is a feather mite, with the handlebar on either side of its mouthparts adapted to lay closely against a cormorants’s feathers and literally suck the trash away. Discovered in Brazil by Fabio A. Hernandes, the rough, reptilian texture of the top of this mite’s mouthparts is thought to help with cleaning, like a bird-based Roomba. Found on neotropic cormorants (Phalacrocorax brasilianus), males of the species are asymmetrical, with elongated legs on one side of their bodies. One theory is this allows males to anchor themselves firmly between feather barbs while mating.

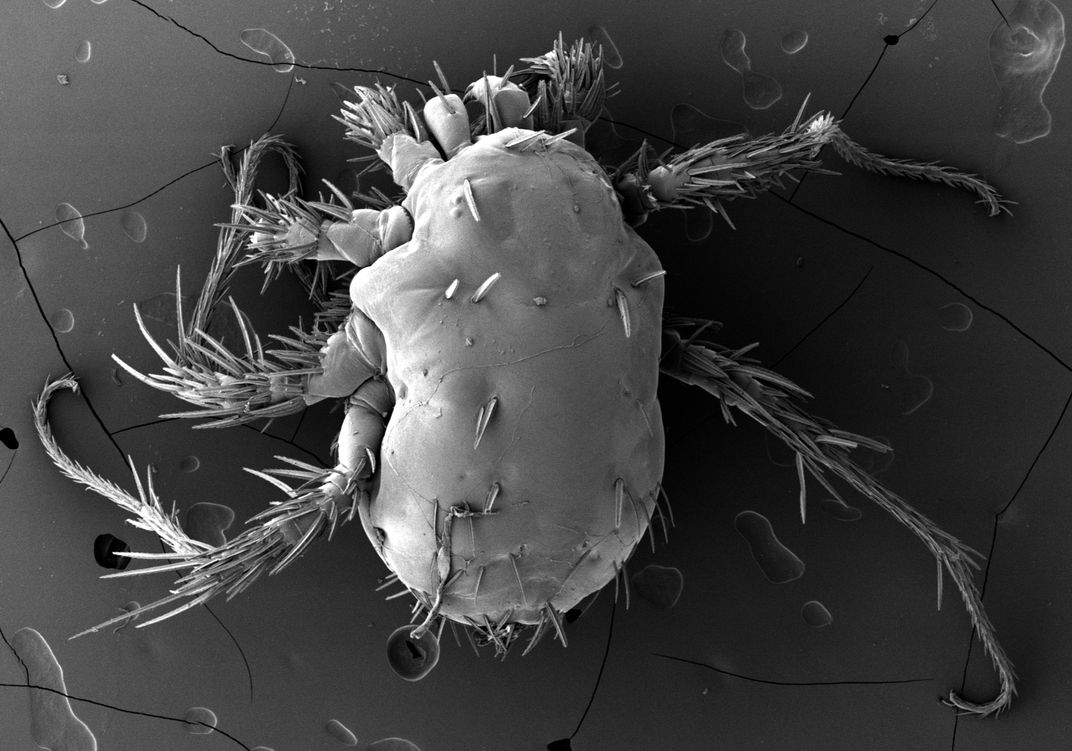

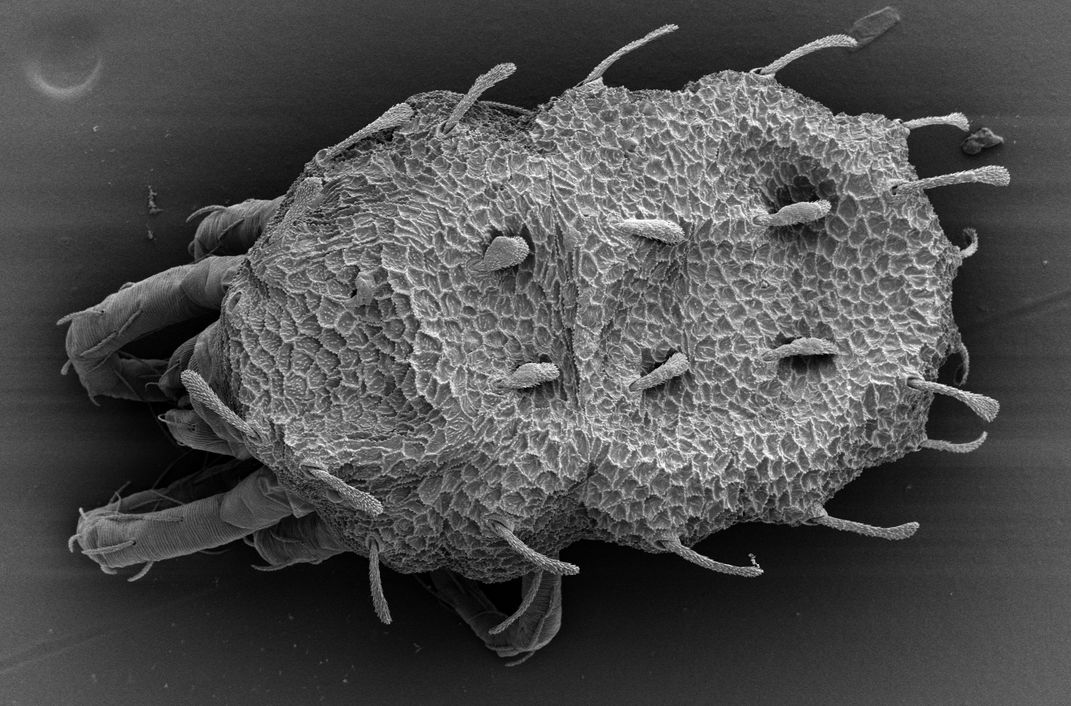

Genus Mononychellus, (unnamed species)

Genus Mononychellus (unnamed species) Like finding money on the street, so many new mite discoveries are made through simple chance. While waiting for a bus in 2014, Peruvian entomologist Javier Huanca Maldonado looked to his left and noticed trees with yellow discoloration. He collected some leaves and found this new species of spider mite, still undescribed at the species level. It pierces leaves to suck their juices with a sharp stylet that emerges from a hole in the middle of its face, making it a likely agricultural pest. Yellow gunk on the face of Mononychellus is leaf tissue and dust.

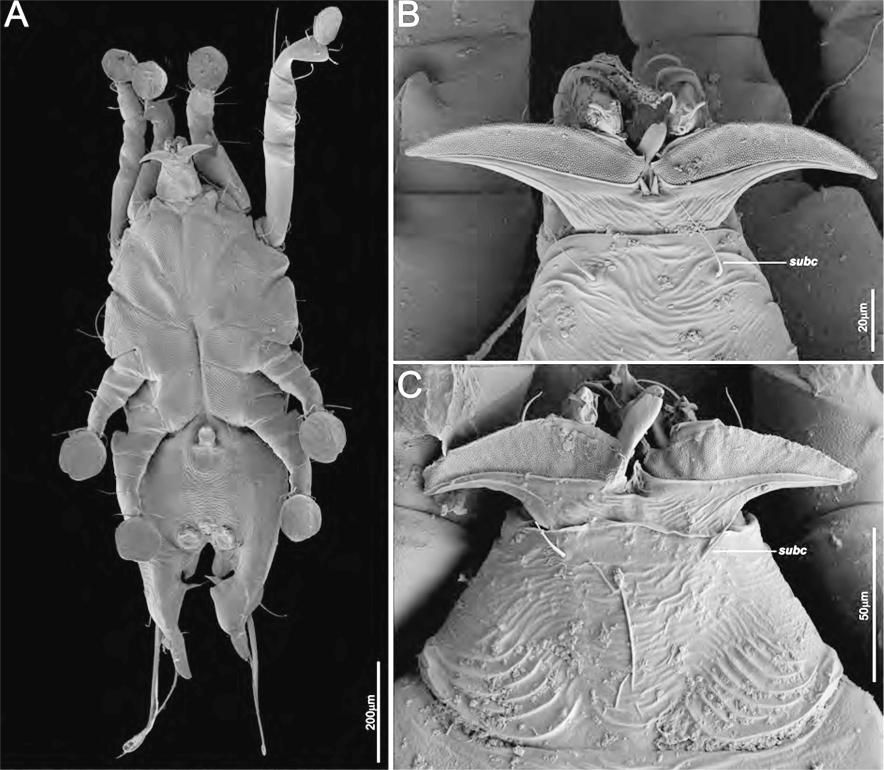

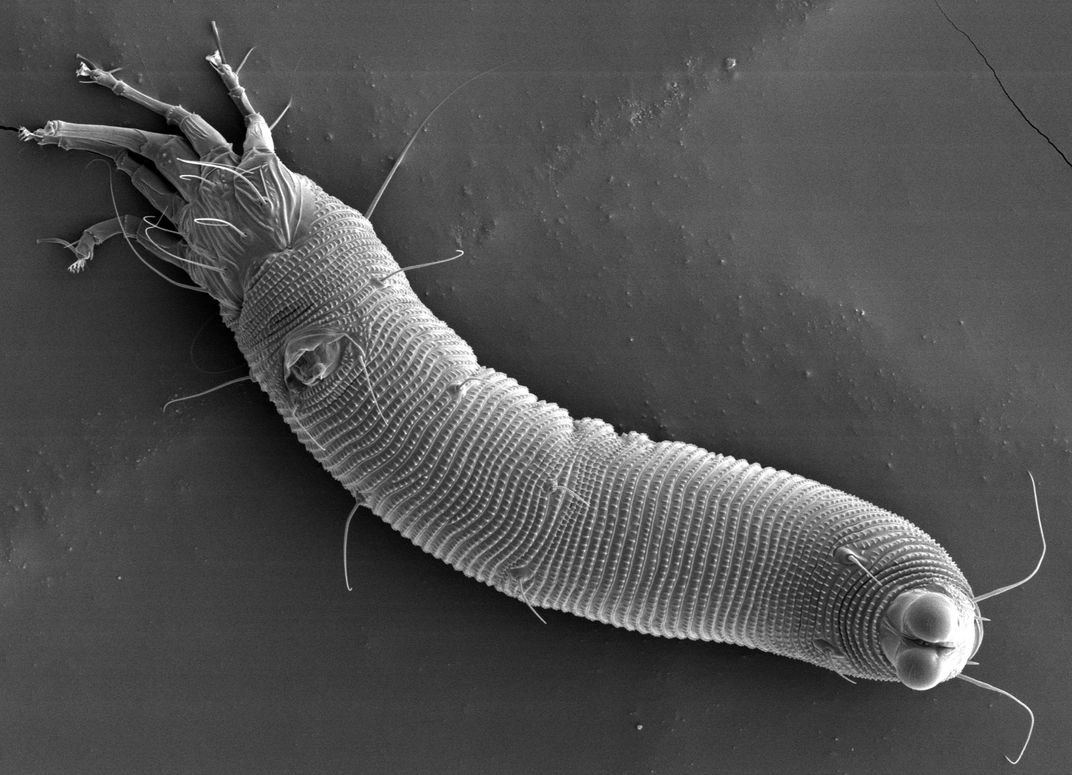

Novophytoptus juncus

Novophytoptus juncus What lovely eyes you have! Whoops, think again: that’s actually the hind end of this mite, which feeds on rushes. “It’s just mooned you,” Ochoa says. Those two bulbous structures actually work like pseudolegs, and are located at the end of the opisthosoma, upon which the mite stands to catch a breeze and drift off in search of a new grassy host. More than 6,000 species of this family of mites are known, each host-specific. So wherever it is floating through the air, it must land upon the plant host it requires or move on. This mite family also claims two other superlatives: they’re Earth’s smallest arthropods, 80 to 120 microns in size—about the width of two human hairs—and are the oldest mite known, having been found encased in fossilized amber.

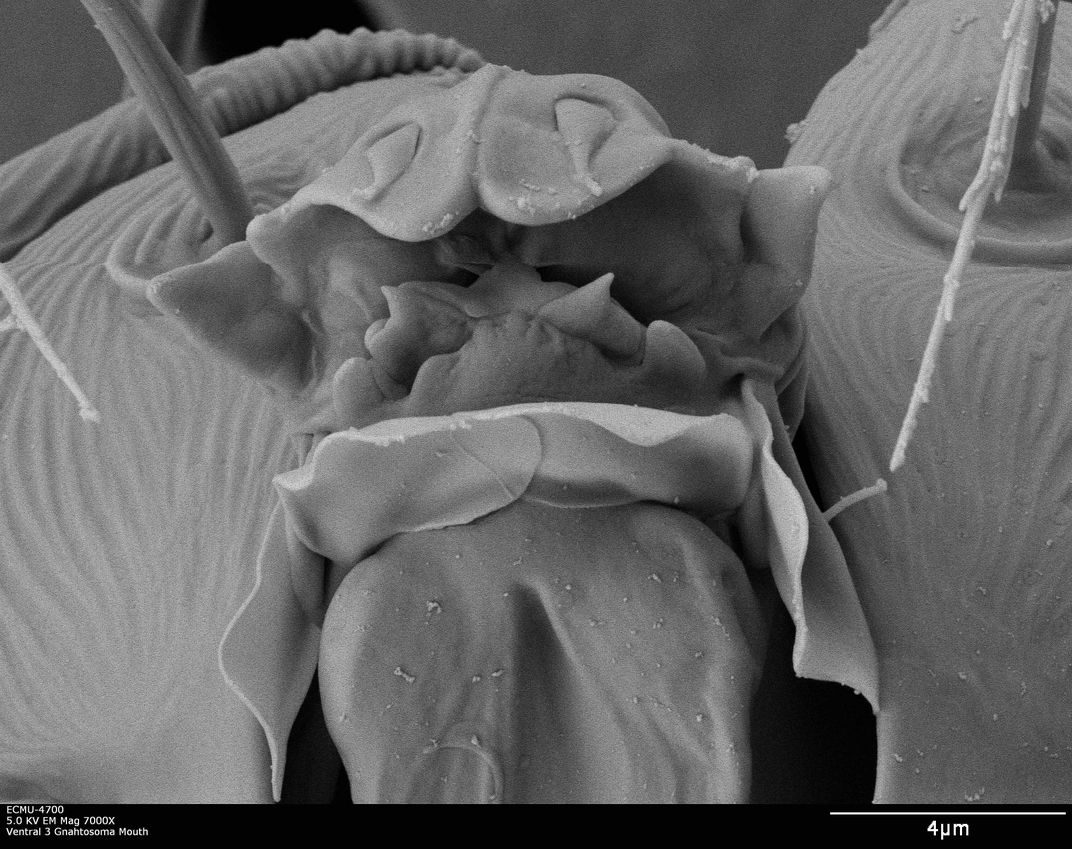

Oligonychus grypus

Oligonychus grypus Found in a greenhouse in Clewiston, Florida, in 2002, this red spider mite is thought to be native to The Republic of Congo (Zaire), and may have come to the United States through Asia or Brazil. Ochoa calls it a “scary but nice” gargoyle—though not so sweet, as it is an effective destroyer of sugar cane, puncturing the undersides of leaves to feed. The leaves later turn red and die. Its U.S. population is increasing rapidly, making it a subject of intense study. Ochoa and Bauchan captured this live image with a low-temperature scanning electron microscope, which allows them to understand the mite’s mouthparts move. “We captured him talking,” Ochoa says.

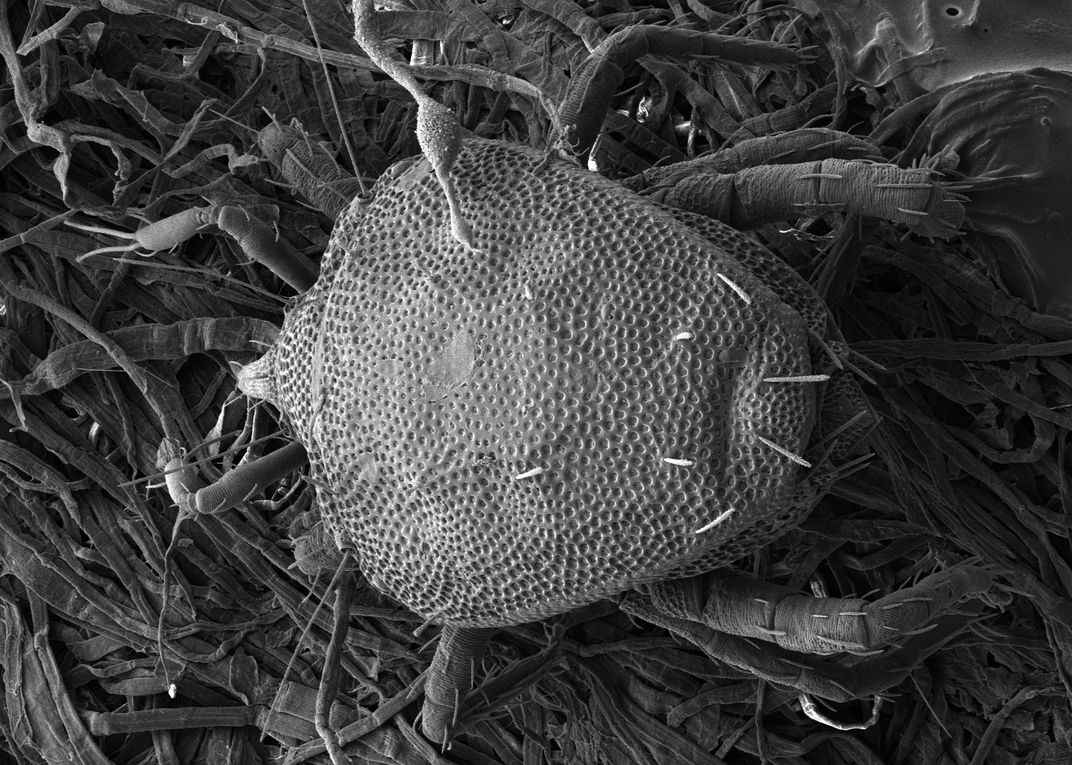

Trachymolgus purpureus

Trachymolgus purpureus No false color here: this brilliant purple hue is this mite’s actual color. Collected in the 1980s in Buffalo National River and Devil’s Den State Park in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas, this unusually stocky, sturdy mite was described and named in 2015 by a team of University of Arkansas and USDA Agricultural Research Service scientists. It has subsequently been found in Ohio and along the St. Lawrence River, as well. Temperature tolerant, it has been observed crawling on rock faces in full sun, and when exposed to liquid nitrogen (-321 F,) to immobilize it for photographing, T. purpureus “would simply run, curl their legs, and roll off the plate. This made imaging live specimens very difficult,” write the scientists who named it.

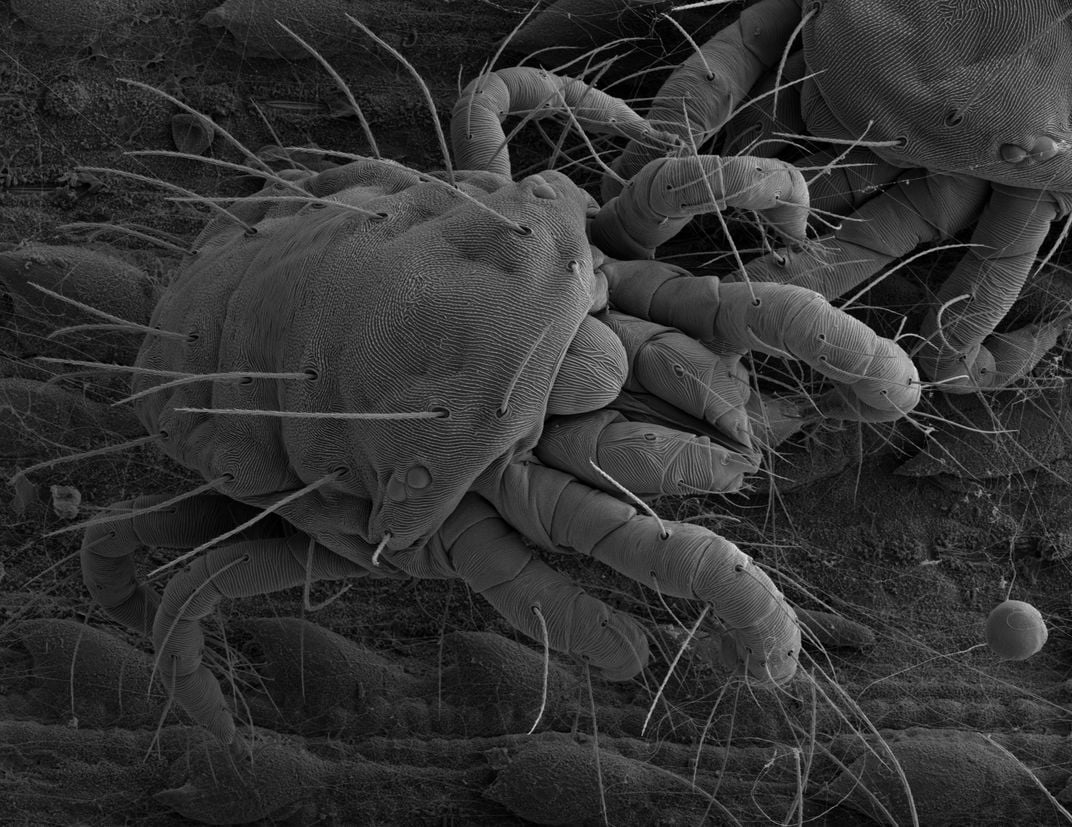

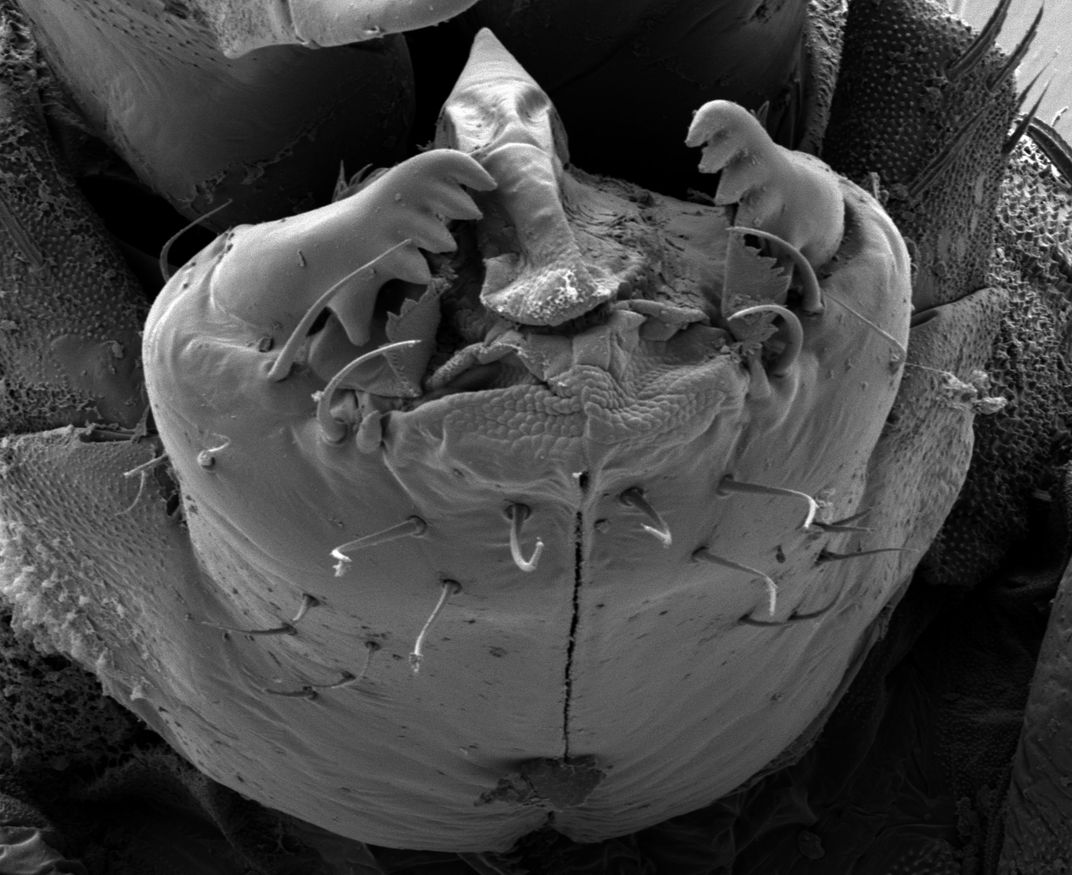

Neocarus proteus

Neocarus proteus Bauchan and Ochoa calls this mite Goat Man. His ‘hands’ are an appendage called rutella each with five ‘teeth’ that help this predatory Brazilian mite hold tight onto other squirming mites as it eats them. N. proteus is found in iron-rich caves and soils in southeastern Brazil, and is from a primitive order. “They are cool mites, very colorful some of them,” Ochoa adds. As with nearly all mite species, little is known about their behavior, development or other aspects of their biology.

This article was orginally published on Smithsonian Insider.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/45/f3452040-8d9a-4ee7-badc-827604b8bd8e/novophytoptus-juncus-plate-1166_030.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)