Family Ties

African Americans use scientific advances to trace their roots

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dna-lab_388.jpg)

Where do you come from? It's a simple question for many Americans. They rattle off a county in Ireland or a swath of Russia and claim the place as their ancestral home. But for many African Americans, a sense of identity doesn't come that easily.

"African Americans are the only ones who cannot point to a country of origin," says Gina Paige, president of African Ancestry, Inc., a company in Washington, D.C. that offers DNA lineage tests. "Italian Americans don’t refer to themselves as European Americans. We are the only group that have to claim an entire continent."

Over the last 20 some years, in part fueled by Alex Haley's book Roots and the subsequent miniseries, more African Americans have tried to uncover clues about their past. A growing number of books and articles outline the fundamentals of genealogical research. State and national African American genealogical societies, many of which offer classes and host conferences for novice and advanced researchers, have aided the search. Electronic access to records has also helped.

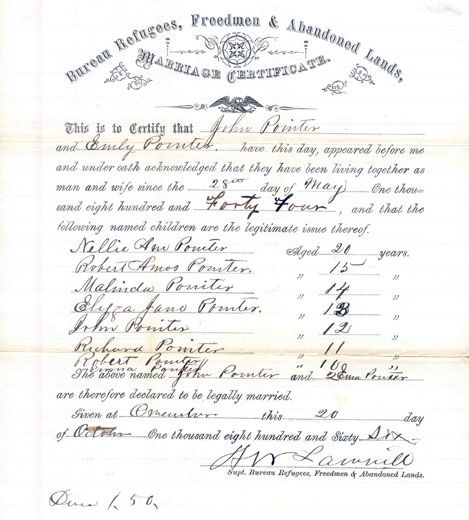

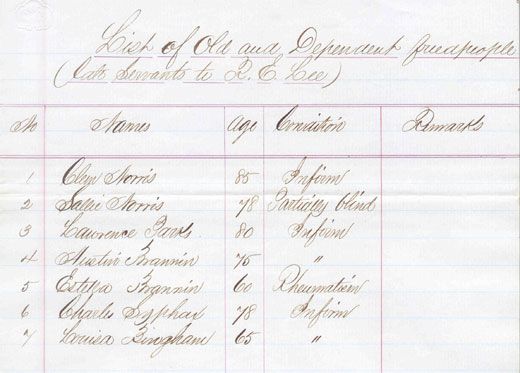

Last month, on Martin Luther King Day, the state of Virginia began the process of indexing and digitizing the records of the Freedmen's Bureau, a group started in 1865 during the Civil War to help provide economic and social relief to freedmen and refugees. The bureau's records, which date from 1865 to 1872, include documents such as marriage certificates, labor contracts and healthcare and clothing receipts. The National Archives made the digitizing effort possible when they put the entire paper collection on microfilm, a job that took nearly five years and resulted in more than 1,000 rolls of film.

People searching for family clues can also comb through slave narratives, plantation and military records, census information and other government documents; but these collections only look back so far. The U.S. Census started counting slaves as late as 1870, and many documents around this time list people not by name but by gender and description. "For decades, perhaps centuries, African Americans were completely disregarded. We were no more than property,” says Betty Kearse of Dover, Massachusetts, who has been researching her own family heritage. "It's up to us to find the names in spite of the fact that many records of our ancestors don’t even include names."

In addition to sifting through microfilm and books, people can now look within themselves—at their DNA—to understand more about their heritage dating back before the 1800s. By locating variations in genetic markers and matching them with indigenous populations throughout the world, scientists can group people into different haplotypes, which can shed light on their ancestors' geographic locations and migration patterns. The tests focus on the Y chromosome, which men share with their father, grandfather, and so on, going back for generations, and also on mitochondrial DNA, which is an exact link to the maternal line.

"Genes tell the true story," says Bruce Jackson, a professor of biotechnology at the University of Massachusetts. Jackson, along with Bert Ely of the University of South Carolina, founded the African American DNA Roots Project, a molecular anthropology study designed to match African American lineages with those in West Africa, a region from which many slaves were taken.

Jackson's interest in genetics began as a child listening to stories about his father's family in Connecticut and his mother's in Virginia. His father's stories all started with "an African kid in 1768,” says Jackson. No one knew the boy's name or where he came from.

Jackson's mother’s heritage culminated in a rumor. "The story was that the matriarch was a white woman, which meant she would have had to have a child with a black man," he says, an occurrence that is historically known to be more rare than children between women slaves and their white owners.

With a master's degree in genetics and a doctorate in biochemistry, Jackson began combining what he knew from the lab with his own family's history. He tested the mitochondrial DNA from his mother's line and found that the rumor was actually true. The sample was of Irish descent, which led him to suspect that his matriarch was an indentured servant in the United States. Going back even further, the DNA matched a haplotype originating from modern-day Russia. After doing some research, he learned that Russian Vikings were prevalent in both Ireland and Scotland.

After he tested his own family's DNA, another family asked Jackson to test their DNA, then another family asked, and the project snowballed from there. Now, with some 10,000 DNA samples to test, the international project is near capacity. "We’re just overwhelmed," he says. "We get responses from all over the world."

Requests from African Americans also inundated fellow geneticist Rick Kittles, who appeared in "African American Lives," a PBS miniseries that tested the DNA of some well-known participants, including Oprah Winfrey. Kittles decided to meet the community demand by collaborating with businesswoman Gina Paige to commercialize his efforts. Since 2003, when they opened African Ancestry in Washington, D.C., they have tested over 8,000 lineages.

"This is a transformative experience for people who trace their ancestry," says Paige. "It causes them to look at their lives and define themselves in different ways. Some do it just because they are curious, some to leave a legacy for their children. Some are reconnecting with Africans in the continent, building schools and buying real estate. Others are connecting with Africans here in the States."

Although African Ancestry claims to have the largest collection of African lineages in the world with some 25,000 samples from Africa, they do not guarantee they will find ancestry from the continent. In general, 30 percent of African Americans who have their DNA tested find they come from European lineages—a statistic that corroborates the well-known stories of white plantation owners impregnating their female slaves. Although the company also does not promise to match the person with one specific ethnic group, they do hope to connect people with the present-day country in which their lineage originated.

Jackson is skeptical of results that are too specific. "You have to be careful," he says, stressing that there is a lot more to learn about different ethnic groups in Africa. "What you can do now, at best, is to assign people to a part of West Africa," Jackson says.

But science is making some breakthroughs. In 2005, Jackson and his colleagues made important progress when they were able to genetically distinguish different ethnic groups living in Sierra Leone. And, although he thinks the database of indigenous African DNA samples is not nearly big enough to make an accurate match with an African American, he feels the work of his postdoctoral students and other students in the field of genetics will certainly help the research on its way. "In about 50 years," he says, "things will be clear."

Tony Burroughs, a genealogist who wrote Black Roots: A Beginners Guide to Tracing the African American Family, cautions people to avoid jumping straight into DNA testing. "If a geneticist is honest, they would say that someone shouldn't do a DNA test before they do research," he says. Burroughs advises a more practical approach to ancestry research: Talk to relatives, and write down as much as possible about the family.

"After collecting oral stories, go to relatives' basements, attics, shoe boxes, dresser drawers to see what they have that has been passed down," he says. "Those pieces will add little pieces to their oral stories. Then leave the house, and do further research." Go to places like cemeteries and funeral homes; search vital records offices, death certificates, birth certificates, marriage records. "No one should do any genetic work until they have gotten to the 1800s and 1700s," he says. "Otherwise that DNA research doesn’t help."

Kearse has been researching her family's roots for more than 15 years. According to her family's oral history, her mother descended from a woman named Mandy, who was taken from Ghana and enslaved at Montpelier—President James Madison's plantation in Virginia. According to the story, Mandy's daughter, Corrinne, had a relationship with the president that produced a child, a claim Kearse is now working with Jackson to try to verify through DNA. When the child, Jim Madison, was a teenager, he was sent away from Montpelier, eventually settling on a plantation in Texas.

"The story has been passed down from generation to generation," says Kearse. "One of the important themes was that when [Jim] was sold away for the first time, Corrine [his mother] said to Jim as he was put on the wagon, 'Always remember you’re a Madison.' " For Corinne, it would be a tool, an instrumental way for her to meet her son again. They never did see each other, but the words never left Jim.

"I hadn’t thought of trying to connect the family through DNA to Madison. I hadn't planned on doing it because the Jefferson and Hemmings story had gotten so controversial and ugly," says Kearse of the recent verification that Thomas Jefferson had children with his slave, Sally Hemmings. She reconsidered after inviting Jackson to a commemoration of former Montpelier slaves set to take place this year.

Kearse and Jackson are still trying to locate a white male descendant of the Madisons who has a clear Y chromosome line to the family. Jackson is going to England in the spring to look for living descendants. However, even if the DNA is a match, it may never concretely link her family to the president because he had brothers who shared the same Y chromosome.

Nevertheless, the match would give weight to a story her family has lived with for generations. "Always remember you’re a Madison" became a source of inspiration for Kearse's early ancestors. Her family, she says, "realized this name came from a president, and it means we are supposed to do something with our lives."

Over the years, the saying came to mean something more. "When the slaves were freed after emancipation, the family added on to the saying,” says Kearse. "'Always remember you’re a Madison. You descended from slaves and a president.' "

But now Kearse has a new understanding of her heritage. "For me, it’s more important to have descended from Mandy, a woman who was captured from the coast of Ghana, survived the Middle Passage, survived the dehumanization of slavery," says Kearse, who is writing a book about her family. "For me, she is the source of pride."