The Fever That Struck New York

The front lines of a terrible epidemic, through the eyes of a young doctor profoundly touched by tragedy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/46/fc466b8d-4b4c-4e62-9c5d-20023f125940/mar2021_b04_prologue.jpg)

Word of the disease in New York City came “from every quarter.” The place was “besieged.” Thousands fled to the countryside—so many that transportation became impossible to find. Others huddled inside their homes. Many died. Hospitals were overrun, and nurses and doctors were among the earliest to succumb. People who ventured out held a handkerchief up to their nose and mouth, fearful of what they might breathe in. Wild claims about miracle drugs and regimens tricked some into believing they could outwit the disease. They couldn’t.

It was 1795, and the yellow fever—which had burned through Philadelphia two years earlier, killing more than 10 percent of the city’s population—had arrived in New York. It would return in 1798, and those two epidemics killed between 3,000 and 3,500 New Yorkers. Hundreds in other parts of the East Coast died in localized outbreaks, almost always in urban centers.

A lethal, highly contagious disease that tears through urban populations and shuts down normal life is a phenomenon we can appreciate during the Covid-19 pandemic. Recognizing these parallels, I revisited a startlingly detailed account of those terrifying outbreaks of more than 200 years ago—a young physician’s unpublished diary, which I came across in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University. It’s an extraordinary, closely observed chronicle of a young man’s life and how the disease changed it.

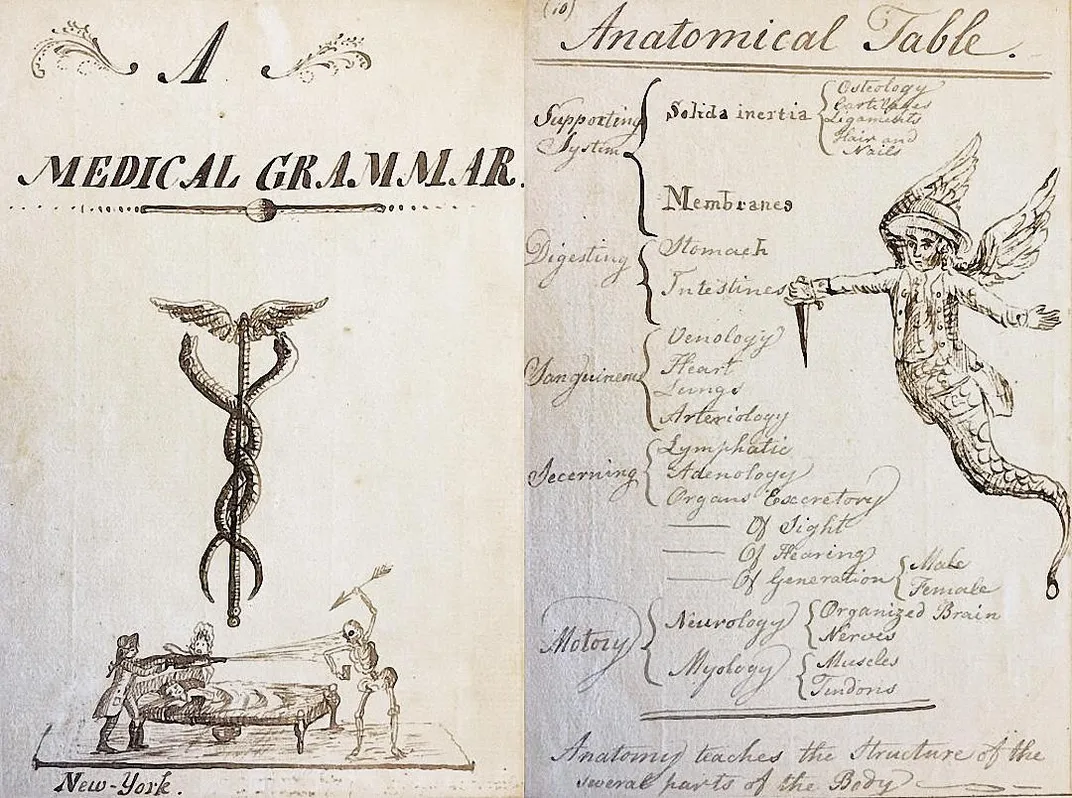

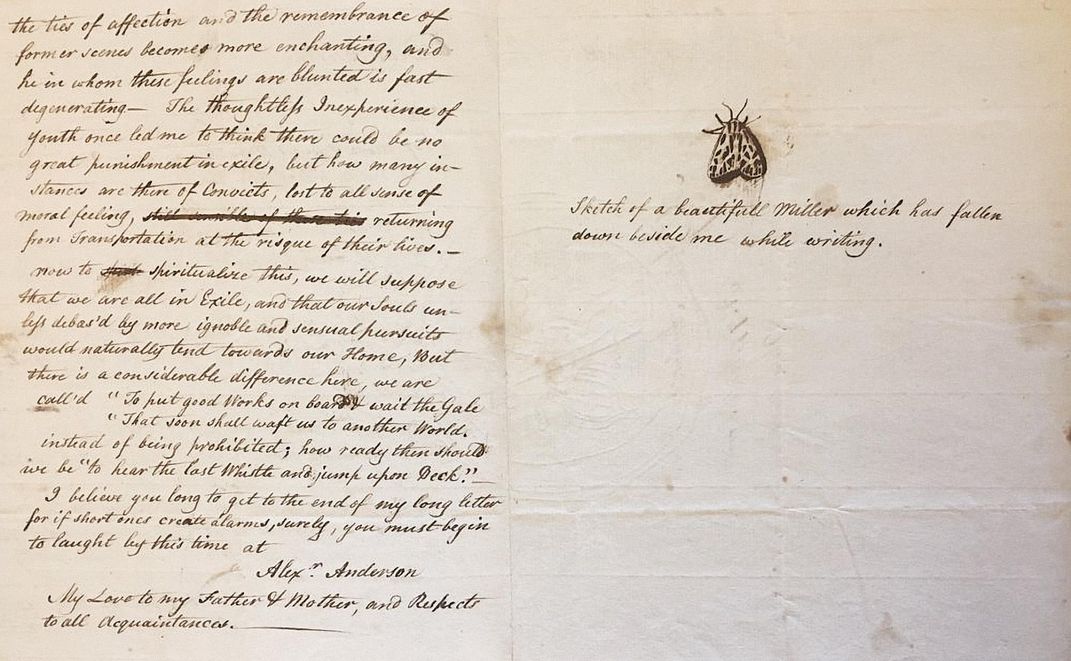

The Manhattan-born Alexander Anderson—or Sandy, as friends and family called him—wrote with great curiosity about the world around him, and even sketched images in the margins. His personality leaps from the page. The diary fills three volumes, the first of which he began in 1793 as a 17-year-old medical student at Columbia. Yellow fever would have such a profound impact on him that he would eventually leave medicine to work instead as an artisan, becoming a renowned engraver. An unfinished portrait of him in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art shows a wide, friendly face with black hair and eyes, evoking the openness with which he seemed to approach life.

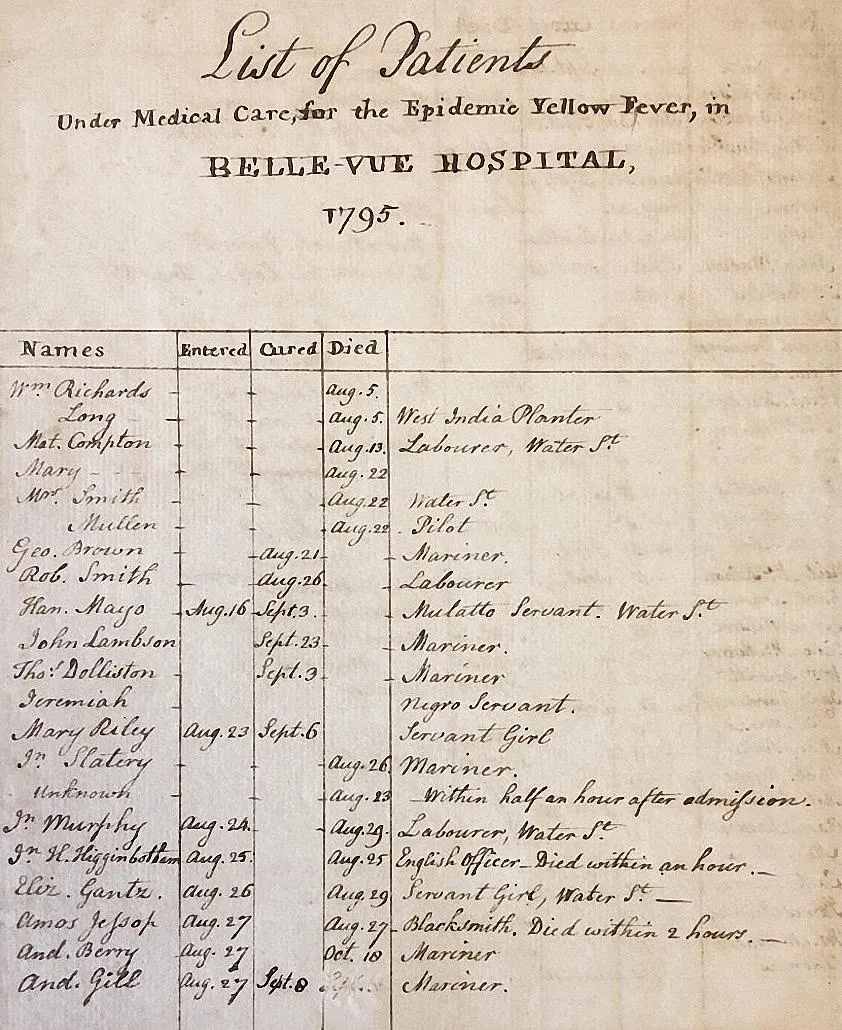

In 1795, with the number of yellow fever cases growing alarmingly, the city of New York opened Bellevue Hospital, where doctors could isolate the seriously ill. It stood several miles upriver from the densely populated area of Lower Manhattan where Sandy Anderson still lived with his parents. Desperate for medical help, the city’s Health Committee hired him as a medical resident at the hospital. The pay was good because the risks were so high; doctors did not know what caused the disease, nor how it spread.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, many European and American medical authorities suspected yellow fever spread through pestilential vapors emitted by rotting garbage. The symptoms of the disease were unmistakable. Some experienced only moderate fever and headache, and fully recovered, but in severe cases—between 15 and 25 percent—patients who had appeared to be on the mend abruptly worsened. Fever spiked, causing internal hemorrhaging and bleeding from the nose, eyes and ears. Some vomited blackened blood. Liver damage led to jaundice, turning skin and eyes yellow—hence the name.

It would take scientists more than a century to discover that the virus was spread in cities by a unique species of mosquito, the Aedes aegypti. Not until 1937 would medical researchers develop a vaccine. (Today, the disease kills around 30,000 people each year, overwhelmingly in Africa.)

The outbreak of 1793 almost exclusively affected Philadelphia, where people sensed it was contagious. “Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod,” one Philadelphian noted at the time. “The old custom of shaking hands fell into such general disuse, that many were affronted at even the offer of the hand.” Similarly, some people held a handkerchief drenched in vinegar to their nose, to filter the noxious air.

When the disease came to New York in 1795, residents recalled the nightmarish experiences of Philadelphians two years earlier. The “ravages made by the Fever in Philadelphia fill the minds of the inhabitants of [New York] City with terror,” Anderson’s mother, Sarah, wrote to him in September 1795.

Upward of 700 New Yorkers died during the fall of 1795, before cold weather killed the mosquitoes and put an end to the year’s epidemic. Commended for his work at Bellevue, Anderson returned to Columbia to complete his medical education.

* * *

By August 1798, Sandy Anderson, now 23 and a fully licensed physician, was reeling after a hard summer. He and his new wife, Nancy, had lost their infant son in July, possibly from dysentery, and Nancy had gone to stay with relatives in Bushwick—a rural area in Brooklyn that required Anderson to take a ferry and a carriage ride of several miles whenever he visited. “This morning I found myself weak, indolent, forgetful, miserable,” he wrote shortly afterward. “‘Twas with difficulty I could drag myself out to see my patients.” A couple of weeks later, he confessed that “I am obliged to support myself by wine and a little Opium.”

New York’s health commissioners had believed that with careful quarantining of occasional cases, the city could avoid another full epidemic of the kind it had seen three years before. At one point in mid-August 1798, city officials welcomed an intense three-day downpour of rain, which they believed would “cleanse” city streets and “purify the air.” “Alas! our expectations in this respect, were dreadfully disappointed,” one New Yorker wrote. The storm was followed by a heat wave, and the water that had puddled in yards, streets and basements was a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes.

For the first time since 1795, Bellevue Hospital reopened. Anderson returned on August 31. Conditions were bad. Twenty patients awaited him; four died by the evening. He admitted 14 more that first day. The deaths were gruesome, and the agony of their loved ones unbearable to witness. “We had some difficulty in getting rid of an Irishman who wish’d to stay and nurse his sweetheart at night,” he wrote. “My spirits sank.” Meanwhile, some of the nurses began getting sick. For a few days in early September, he began recording statistics in the diary—“9 Admitted, 4 Died.”

Anderson abandoned that record-keeping on September 4 when a friend arrived at Bellevue to tell him that his wife was sick with the fever; on the following day, his father came to the hospital to say that Sandy’s brother John had fallen ill as well.

For a few days Anderson tried to care for everyone—his wife in Bushwick and the rest of his relations downtown, plus dozens of Bellevue patients. Then, on September 8: “A heavy blow!—I saw my Brother this morning and entertain’d hopes of his recovery. In the afternoon I found him dead!” Yet he could not rest to grieve. “I left my poor parents struggling with their fate and return’d to Belle-vue.” Before setting aside the diary that day, he paused to sketch a small coffin next to the entry.

His father died on September 12. Anderson sketched another coffin next to the entry. In Bushwick, he found his wife in a shocking condition: “The sight of my wife ghastly and emaciated, constantly coughing & spitting struck me with horror.” She died on September 13; he drew another coffin. His mother, the final member of his immediate family, took ill on the 16th and died on the 21st; another coffin. “I never shall look upon her like again,” he wrote.

By the time the outbreak abated, as mosquitoes died off in cold weather, Anderson had lost eight members of his family and “almost all my friends.” Distraught, he quit his job at Bellevue and rejected other offers of medical work. A few months earlier, he seemed to have everything before him. The 1798 epidemic wiped it all away.

When I first read Anderson’s diary in Columbia’s rare books library, in 2005, I found myself weeping at the human loss and the sight of sketched coffins in the margins by a diarist I found so appealing. His experience had just been so relentless. I had to leave the quiet seclusion of the library and walk over to the anonymous bustle at Broadway and 116th to collect myself.

We have grown accustomed to learning about an epidemic from statistics. Throughout Covid-19, we have grasped at numbers, charts, percentages. Six feet apart. Number of tests per day. Spikes and curves. And well over two million deaths worldwide.

Anderson’s diary reminds us of those who experience the daily life of an epidemic. It was the very dailiness of his chronicle, the intimacy of his portrait of his encounter with nightmarish disease, that drew me back as another pandemic emerged in 2020.

“I took a walk to the Burial ground where the sight of Nancy’s grave rivetted my thoughts to that amiable being, and was as good a sermon as any I have heard,” he wrote in late October 1798. A few days later he commented, “My acquaintances are fast flocking into town [after evacuating] and many a one greets me with a rueful countenance.”

On New Year’s Eve, he offered “a few remarks on past year”: “A tremendous scene have I witnessed,” he wrote, “but yet I have reason to thank the great Author of my existence.” In addition to his religious faith, he added that “I have made more use of liquor than in all my life together, and sincerely compute the preservation of my life to it.”

It took time, but Anderson moved on. He never returned to practicing medicine. He also seems to have ceased keeping a diary after 1799. Instead, he became an engraver acclaimed for carving images on blocks of wood—talents that eventually made him much more famous in his time than he was as a doctor. He remarried, had six children and ultimately professed pride in having chosen an artisan’s life over a physician’s high pay and social status. When he died in 1870, at age 94, the New York Historical Society remembered Anderson as a “pioneer in [the] beautiful and useful art” of wood engraving.

Though his engravings are undeniably charming, it’s Anderson’s account of his work in the yellow fever wards that resonates most powerfully today. Anderson’s diary reveals a similar slow-motion horror story to the one threatening us now. Embedded in those diary entries, in the ink that has turned brown after more than 200 years, is a reminder that he sought to help, suffered and survived. It has helped remind me that we will, too.

Engineering Immunity

A bracing history of the ingenuity and value of inoculations

By Amy Crawford

C. 1000 | Puff of Prevention

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/90/7690e49a-fe86-4911-9aab-c2034b1fb537/1.jpg)

Its origins are murky, but inoculation against smallpox most likely began in China, during the Song dynasty. Prime Minister Wang Tan’s empire-wide call for a weapon against the disease was answered by a mysterious monk (or possibly a nun) who visited the PM from a retreat on Mount Emei. The monastic’s technique—blowing a powder of ground smallpox scabs into the patient’s nose—remained in use for centuries in China.

1777 | Troop Strength

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/c2/07c24b07-c6c0-4507-9353-a8906814e919/mar2021_b07_prologue.jpg)

George Washington, who’d contracted smallpox as a young adult, ordered inoculations against the disease for all Continental regulars; some 40,000 men were treated by year’s end. The procedure involved cutting the skin and inserting diseased tissue from a smallpox patient. “Should the disorder infect the Army,” Washington wrote, “we should have more to dread from it, than from the Sword of the Enemy.”

1885 | Pasteur's Gamble

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/1f/631f080b-6b6e-4f64-b55d-7c3dc4eaa55a/mar2021_b08_prologue.jpg)

After a rabid dog mauled a 9-year-old boy from Alsace, Joseph Meister, his mother took him to the Paris laboratory of Louis Pasteur, who was experimenting with a rabies vaccine made from the spinal cords of afflicted rabbits. Pasteur hadn’t tested it on humans but agreed to treat the boy. Spared from the deadly brain virus, Joseph grew up to work at the research institute Pasteur founded in 1887.

1956 | The King and His Followers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/45/40456770-ee73-4d7e-ba2d-2b01ac87c3bc/mar2021_b06_prologue.jpg)

In the mid-1950s, millions of American children received the newly developed polio vaccine. But public health authorities lamented that teens and adults were not getting the shot. Then Elvis Presley, 21, agreed to get jabbed for the cameras before performing on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Photos of the injection helped improve vaccine acceptance: By 1960, polio incidence was one-tenth of the 1950 level.