The Fight Against Elephant Poachers Is Going Commando

In central Africa, a former Israeli military trainer and his team are deploying battle-tested tactics to stop the runaway slaughter of elephants

The port of Ouesso, in the Republic of Congo, sprawls along the east bank of the Sangha River, a wide, murky stream that winds through the heart of Africa. One recent morning, a crowd gathered around a rotting dock in the harbor to gape at the sight of seven white men stepping gingerly into a 30-foot-long pirogue. Carved out of a tree trunk, and barely wide enough to accommodate a person with knees squeezed together, the pirogue rocked dangerously and seemed about to pitch its passengers into the oil-slicked water. Then it steadied itself, and we settled onto blue canvas folding chairs arranged single file from bow to stern. The shirtless captain revved up the engine. The slender craft puttered past clumps of reeds, scuttled rowboats and an overturned barge, and joined the olive green river.

We were heading upstream to a vast preserve in the Central African Republic (CAR), and between here and there lay 132 miles of unbroken rainforest, home to elephants and western lowland gorillas, bongo antelopes, African forest buffaloes, gray-cheeked mangabeys and bush pigs, as well as soldiers, rebels, bandits and poachers. Leading our group was Nir Kalron, a 37-year-old former Israeli commando who has built a thriving career selling his military expertise to conservation groups and game parks across Africa. Kalron’s sidekick, Remi Pognante, served in French military intelligence in Afghanistan and Mali. They were joined by a three-man documentary film team from the United States and Spain, the photographer Pete Muller and me.

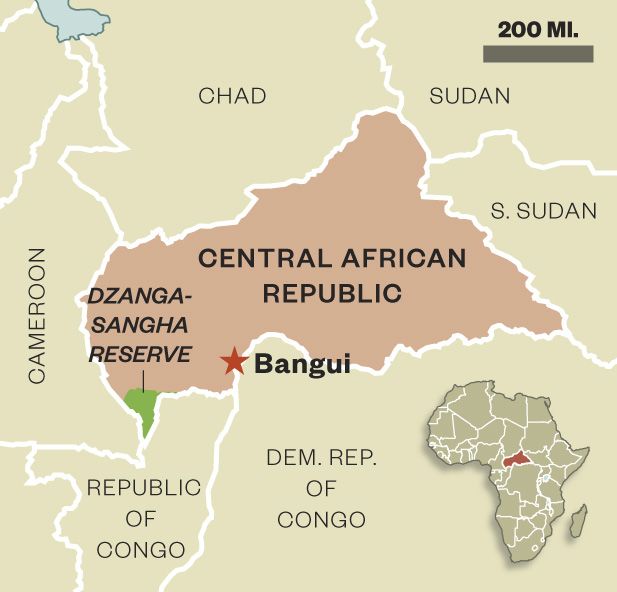

Kalron had been working to rescue several thousand forest elephants in the Dzanga-Sangha Reserve, 1,544 square miles of rainforest in southwestern CAR. The smallest of three elephant species, with oval-shaped ears and straighter, downward-pointing tusks, these creatures inhabit the densely wooded rainforests of Liberia, Ivory Coast, the two Congos and the Central African Republic. But nowhere is their predicament worse than in CAR, site of one of the continent’s most notorious animal slaughters: the massacre three years ago of 26 forest elephants by Sudanese ivory hunters wielding semiautomatic rifles.

Shortly after the killings, Western conservationists based in the neighboring Republic of Congo asked Kalron and the security firm that he founded, Maisha Consulting, to protect the remaining elephants. Through a unique combination of gritty freelance diplomacy, high-tech surveillance and intimations of powerful connections, Kalron helped quiet the violence. Today, according to the World Wildlife Fund, which administers the park alongside the CAR government, Dzanga-Sangha is one of the few places in Africa where “elephant poaching is now rare”—a little-known success on a continent plagued by illegal animal killing.

The killing in Zimbabwe of a protected lion named Cecil by a U.S. trophy hunter last July sparked justifiable outrage worldwide, but the far greater crime is that heavily armed gangs, working with sophisticated criminal networks, are wiping out elephants, rhinos and other animals to meet the soaring demand for ivory, horn and the like in China, Vietnam and elsewhere in the Far East. Between 2010 and 2012, ivory hunters shot down an astonishing 100,000 elephants across Africa—more than 60 percent of central Africa’s elephant population has been lost during the ten-year period beginning in 2002—according to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. To counter that unprecedented decline, governments and other wildlife custodians have increasingly adopted a range of military tactics and farmed out work to private companies. Some of these outfits specialize in training park rangers. Others deploy state-of-the-art radar, supersensitive buried microphones, long-range cameras and drones to monitor protected areas. But even the experts agree that Maisha (Swahili for “life”) operates in a class of its own. It offers what Kalron calls “one-stop shopping,” selling intelligence, surveillance equipment, military training and even conflict resolution in Africa’s hardest-hit region.

“We’ve got people on our staff from every discipline—analysts from the inner sanctum of Israeli intelligence, special operations guys, technical experts,” says Kalron. “We’ve got Arab speakers, Somali speakers, Hausa speakers. Each person is at the top of his field. They join us not only for the money, but because they have an emotional stake in the work.” When it comes to poaching, he adds, “if you don’t say, ‘I want to get these guys,’ then you’re not for Maisha.”

I’ve covered poaching in Africa for more than two decades, from Kenya to Zimbabwe to Chad, observing how a brief period of hope in the 1990s and early 2000s gave way to the horrifying wanton slaughter of today. It strikes me that Kalron’s approach, which is not without controversy, is worth looking into. Can a privatized army apply the techniques of counterinsurgency to the conservation wars? Or do such militarized tactics invite only more disorder, while failing to address the economic and social roots of the poaching problem? So I grabbed the chance to join Kalron on a journey to the site of the forest elephant massacre to gauge the impact of his interventions there. As it happened, that’s where I ended up running through the forest to save my own life, confronted by an unappreciated dimension of the poaching epidemic, what I’ve come to think of as the revenge of the wild: the hunted turned hunter.

**********

Still in the Republic of Congo, we motored up the Sangha in our canoe, passing unbroken tropical forest, and stopping in the port of Bomassa near the border. We climbed the riverbank for a call at the headquarters of Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, where Kalron and his fellow former commandos have been training Congolese rangers.

When Kalron initially took on that job, he told me as we walked up the muddy steps, he was surprised that the rangers were not just inept from a lack of training but also physically weak. “These guys had manioc muscles,” said Kalron, referring to the starchy, low-protein Congolese dietary staple. But the rangers were accustomed to hardship, and Kalron and Pognante got them to run miles each day and practice wresting poachers into custody. The Maisha team also, as discipline for being late, divided them into groups of eight to carry a half-ton log. If the rangers spoke out of turn, Kalron and Pognante sealed their mouths with duct tape and had them sing the Congolese national anthem. “We didn’t try to break them mentally, but that’s what happened,” Kalron said. Over six weeks, though, only one ranger dropped out. “These guys professionalized our anti-poaching teams,” says Mark Gately, the Wildlife Conservation Society country director for the Republic of Congo, who hired Kalron and Pognante. “I don’t know of anyone else who could have done the job they did.”

As we continued motoring upstream, Kalron pointed out a Cameroonian Army post on the west bank, where, he says, soldiers fired AK-47s over his head in a (failed) shakedown attempt on one of his last trips. A few miles farther along, we reached the border. A tattered Central African Republic flag—bands of blue, white, red, green and yellow—fluttered over a shack. Scrawny chickens pecked at weeds; a rusting sign urged “Prevent AIDS by Abstinence.”

CAR, which freed itself of French rule in 1960, ranks at or near the bottom in every category of human development, weighed down by decades of exploitation, corruption, violence and poverty. The recent surge in animal poaching is linked to the political chaos. In 2003, former army chief François Bozizé seized power with the support of Chad’s oil-rich president, Idriss Déby. But when the relationship ruptured, in 2012, Déby encouraged a coalition of mainly Muslim rebels—Muslims make up 15 percent of CAR’s population—to seize control of the country. The coalition, called the Séléka, hired Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries, and they captured the capital, Bangui, in March 2013. It was just two months later that, with the Séléka’s apparent complicity, 17 Sudanese ivory hunters invaded Dzanga-Sangha, climbed a game-viewing stand and gunned down 26 elephants, hacked out the tusks and left the corpses. Exactly what became of the ivory isn’t known, but the best guess is that the poachers trucked it to Bangui or across the border to Sudan, from which it was smuggled to the Far East. (Months later, the Séléka were driven out of Bangui by a mainly Christian paramilitary group, the “anti-balaka,” which massacred numerous Muslim civilians and drove nearly half a million people from the country. Now CAR is run by a newly elected government committed to stabilizing the country after an interim period overseen by 6,000 African Union peacekeepers and a few hundred French special forces. Some of those troops remain on the ground.)

When Kalron first arrived at the scene of the forest elephant massacre, the meadow was littered with skulls, bones and rotting pieces of flesh. Seeking advice and contacts on the ground, Kalron had phoned Andrea Turkalo, a Cornell University-affiliated conservation scientist who has studied elephants at Dzanga for more than two decades. She was in Massachusetts after fleeing the park for the first time in 26 years: “I got this call out of the blue. I said, ‘Who the hell is this?’ Nir said, ‘We’re going to go in and see what we can do.’ I said, ‘What?’”

Turkalo urged Kalron to get in touch with a man named Chamek, a Muslim who owned a small shop in Bayanga, the town nearest the park. He and a small group of traders had established good relations with the Séléka militia, persuading the rebels to respect the local population. With Chamek making the introductions, Kalron and his crew, including French and Arabic speakers, met the Séléka commander in front of his men. They proffered manioc and pineapples, and handed out boxes of anti-malaria tablets and first-aid kits. After several more trips, and more bestowing of gifts, including shoes, a Koran and a pocketknife, they extracted a promise from the rebel commander and his men to protect animals in the park from further poaching.

Kalron and his team also recovered spent AK-47 cartridges at the elephant massacre site—and shed new light on the atrocity. The cartridges matched ones that they’d found at another elephant killing ground, Bouba Ndjida National Park in Cameroon, where poachers killed as many as 650 elephants in 2012. Cartridges from both sites were manufactured in Iran and used almost exclusively by paramilitary groups with backing from the Sudanese government. “The evidence gave a compelling portrait of a Sudanese poaching gang,” says Varun Vira of the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS) in Washington, D.C., which put out a report based on Kalron’s fieldwork and briefed the U.S. Congress and State Department on the crime.

Tito Basile, the manager of Dzanga-Sangha, said that without Maisha’s intervention, the Séléka would have looted the park, killed guards and slaughtered more elephants. “It would have been very difficult to face these Séléka militiamen on our own,” he told me as we swatted mosquitoes on the porch outside his office in the gathering darkness.

Naftali Honig, director of a Brazzaville-based nongovernmental organization that lobbies to tighten anti-corruption statutes, says Kalron’s crew was uniquely qualified to resolve the crisis nonviolently. “You needed someone present there who had a capacity to see eye to eye with the rebels who had taken over the country, and Maisha could do that,” he says. “The average conservation group will not have conflict-resolution negotiators on its staff.”

Kalron and company “did something decisive,” says Turkalo, the U.S. researcher, “going in there unarmed, talking to people whom we thought were marauding lunatics. They are the real deal.”

**********

Kalron grew up in Yavne, a coastal town south of Tel Aviv, the son of a navy pilot who served in the Yom Kippur War; his maternal grandfather was a secret agent in the Shai, the precursor to the Mossad. As a kid Kalron was adventurous and had a hankering for trouble. “My mother didn’t like me hanging out with him,” said Omer Barak, a former Israeli Defense Forces intelligence officer and journalist who has known Kalron since kindergarten. As boys Barak and Kalron played in huge dunes on the outskirts of town; Kalron liked to leap off the summits and bury himself in the sand. “He always had the urge to head out to the most dangerous places,” says Barak, who now works for Maisha Consulting.

Kalron joined the Israeli special forces in 1996 and was dispatched to Lebanon, where he carried out covert operations against Hezbollah guerrillas. He finished his service in 2000. For several years he worked for an Israeli company that brokered sales of attack helicopters and other military hardware to African governments, but he soured on that. “I could be sitting having coffee in Africa with a Russian guy who then was selling weapons to Hezbollah,” he says. “It didn’t feel right.” So he got a job training Kenya Wildlife Service rangers at Tsavo National Park, which was struggling to hold off Somali bandits who were killing elephants. “The poachers were using heavy weapons. It was a real war,” he says. “I realized, this is what I want to do.”

As the canoe motored up to the CAR border post on the Sangha River, a handful of troops and officials in rags came alive at the sight of our unlikely group. We got out of the boat and for half an hour Kalron chatted up the soldiers and immigration officials in French. He returned with our stamped passports. “How does that Guns N’ Roses song go? ‘All we need is a little patience,’” he said with a grin.

Moments later we were motoring upriver again, on our way to the Dzanga-Sangha Reserve to see how the elephants were faring. Long after dark, the lights of a jungle camp glimmered on the eastern bank of the Sangha. After 14 hours on the river, we pulled up to a dock and carried our bags to an open-walled house at the base of a trail lined with seven thatched-roof bungalows. This was the Sangha Lodge, owned by a South African ornithologist, Rod Cassidy, and his wife, Tamar. “The tourists are starting to trickle back,” Cassidy told us, as we shared a dinner of lamb, homemade chutney and cold beer.

The next morning, Kalron led us in a four-wheel-drive vehicle down a track through the jungle. Several times we got out and pushed the vehicle through muddy pools of water. After half an hour we reached the park headquarters: bungalows around a dirt courtyard, with paintings of the indigenous wildlife—leopards, hippos, crocodiles, pangolin (anteater-like mammals), bongos, forest buffaloes, wart hogs, mongooses—covering the scuffed walls. While Kalron discussed security with the park superintendent, I came upon an incongruous sight: a scrawny white man of late middle age, skin burnished to the color of a chestnut, using WiFi to check his email on an aging laptop and speaking with a New Jersey accent.

He was Louis Sarno, the musicologist, who first came here in the 1980s to study the music of the Bayaka Pygmy clan, which he describes in his book-and-CD package Bayaka: The Extraordinary Music of the Babenzele Pygmies. Sarno, a Newark native, stayed on to live among the natives, married a Pygmy woman and adopted two children. When the Séléka seized the area in early 2013, Sarno fled with the Pygmies into the forest, building shelters out of sticks and hunting antelopes and porcupines. “After three weeks the Séléka left; we thought it was clear, and then another group of Séléka came and I was told it was better to evacuate,” said Sarno, who was wearing a black fedora, khaki shorts and a tattered “Smoking Since 1879 Rolling Papers” T-shirt. Sarno fled downriver to the Republic of Congo with Turkalo, the American researcher; he had hitched a ride back upriver with Kalron and crew.

I hiked with Kalron to the elephant massacre site—the Dzanga bai, a clearing the size of a dozen football fields, where hundreds of animals gather day and night to ingest nutrients from the muddy, mineral-rich soil. Trees thrust 80 feet into the metallic gray sky. Heavy rain had submerged the trail in waist-deep water, turning the ground into a soup of mud and elephant dung. Tété, our Pygmy guide, whom Kalron calls “the great honey chaser” because of his ability to climb impossibly tall trees and collect dripping combs to feed his family, led the way through the swamp. He kept an eye out for forest gorillas and poisonous snakes infesting the water.

When we arrived at the viewing stand, the clearing was teeming with life. I counted three dozen elephants—preadolescents, babies and one old bull that had covered himself completely in mud. Lurking around the edges of the clearing were a dozen giant forest hogs and a small group of sitatunga, kudu-like antelopes with chocolate fur and spiral horns.

Kalron and Pognante checked the batteries on four concealed cameras that provide a panoramic view of the clearing. Kalron hoisted himself onto the roof to examine the direction of the satellite dish, which sends live feeds from the cameras to the reserve’s headquarters and to Maisha’s office in Tel Aviv. He also replaced the antenna and made sure the solar panels that charge the batteries were intact. The elephants kept coming. After an hour, the number had grown to 70; they were peacefully drinking, trunks embedded in the mineral-rich mud. “There were no elephants here for a week when we found the carcasses,” Kalron said, adding that the presence of many calves was a sign that the elephants had gained confidence since the slaughter.

Kalron and Pognante decided to remain in the viewing stand overnight to listen to the elephants. Just before dusk, I started back down the trail with Tété and the WWF’s Stephane Crayne, who had returned to Dzanga-Sangha park two months earlier to resume the conservation group’s operations there. As we rounded a corner and emerged from the jungle, just a few hundred feet from the park entrance, Tété froze. Ahead of us, lolling in a pool beside the gate, was a huge bull elephant.

Tété stared at the elephant, clapped his hands and let loose a stream of invectives in Bayaka. The elephant sprayed water, snorted, flared its ears and lumbered toward us. Tété turned and ran down the trail. A single thought passed through my mind: When your tracker bolts for his life, you’re in trouble.

We veered off the trail and cut through a muddy field. The slime yanked a sneaker off my foot. Tété plunged deeper into the forest, dodging tree trunks, six-foot-high anthills and ankle-deep streams. I could hear a beast crashing through the forest yards away. Few things are more terrifying, I realized, than a rampaging elephant that you can hear but not see. We slogged for an hour through reed beds and waist-deep muck before finding refuge in a ranger station.

Kalron showed up at the lodge the next morning, and we told him what had happened. “That’s Jackie Two,” he said, adding that the bull had charged nearly everyone who has worked inside the park. “He’s got a chip on his shoulder. You’re lucky he didn’t kill you.” Later I phoned Turkalo in Massachusetts, and she attributed Jackie Two’s bad temper to trauma: A poacher had shot his mother dead in front of him when he was an infant. My encounter with the bull suggested to me that this greed-fueled phase in the killing of Africa’s wild animals may have consequences that are even more profound than people have thought. The traumatized survivors of poaching sprees are perhaps acquiring a new sense of who humans are: They are learning, it seems, to regard us as the enemy—even to hate us.

**********

Any private security force raises questions about accountability: Maisha is no exception. In Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the private nonprofit organization African Parks hired Kalron and his company to train rangers, but they ended up taking a more aggressive role. They chased a band of poachers through the bush for several days and wound up engaged in a gun battle with the gang near the border of South Sudan. “In general we are unarmed, but that time we got permission from the government to carry weapons,” Kalron admits. (Nobody was killed in the skirmish.) In this case, he says, the mission, conducted jointly with the army and rangers, was fully authorized by the military: “We are extremely careful in how we do active operations.”

And since a security outfit’s revenue depends on responding to threats, it seldom has an interest in minimizing the danger. At a recent European Union strategy conference on protected-area management, held in Brussels, a few speakers and audience members accused Maisha and others of hyping the risk posed by the Somali Islamist militant group al-Shabab and the Sudanese poaching gangs inside Africa’s game parks. Kalron responded by displaying photos of Séléka rebels carrying recoilless rifles and machine guns in Dzanga-Sangha. Skeptics also argue that targeting the armed gangs in the anti-poaching struggle ignores the larger problems. The South African writer Adam Welz has argued that “the continental-scale slaughter of rhinos and elephants continues to intensify,” while other approaches to saving wildlife have been given short shrift, “including improving justice systems and launching efforts to reduce consumer demand for wildlife products.”

True enough, but I wonder if it isn’t asking too much that Kalron and company should not only meet armed bandits head-on but also eliminate high-level political malfeasance and counter deep economic forces. Kalron himself feels the criticism is misplaced. “Instead of focusing on solving problems, these [critics] are saying, ‘fight the demand.’ This kind of thing drives me crazy,” Kalron told me. “What should I do, take over China? My specialty is trying to stop the bleeding. Using paramilitary and law enforcement stuff can be highly effective. But—and there’s a big but—if you don’t have the ability to work with local authorities, and confront corruption and tribal issues, then you’ll fail.”

Part of Maisha’s success is due to bringing new technologies into remote forests and parks where smugglers had long operated out of sight. Kalron had shown me some of his latest gear in Tel Aviv, in a field near Ben Gurion Airport where half a dozen Maisha staff members met up. Beside four-wheel-drive vehicles and a table with a laptop computer, Kalron tested a DJI Phantom 2 pilotless quadricopter equipped with a 14-megapixel camera and WiFi for live video streaming. Kalron and I walked through the bushes to inspect a custom “snap trap” camouflaged in a thorn tree: It consists of an unattended camera with a motion detector capable of distinguishing humans from animals, an acoustical receptor that can detect a rifle shot, and a spectrum analyzer that picks up the presence of a poacher’s radio or cellphone. The camera transmits real-time images via satellite and has enough battery power to stay concealed in the bush for a month or more.

Then the demonstration began: A “poacher” wandered past the snap trap, which captured his image and relayed it to the laptop. Alerted to the presence of an armed intruder, a staff member deployed the drone. It hovered 100 feet above the bush, transmitting high-definition images to the computer. The poacher fled, pursued by the quad. The Maisha team unleashed a Belgian shepherd dog; a small video camera attached to his collar transmitted data in real time. The dog leapt up, grabbed the padding on the poacher’s arm, and wrestled him to the ground. “We’ll place this [setup] in Dzanga-Sangha,” Kalron said. “It will be perfect there.”

Having spent a good deal of time with Kalron and seen him and his coworkers in action, and knowing well the ruthlessness of Africa’s new breed of high-powered poachers, I have come to share Turkalo’s view of Kalron’s approach: “We need more people with real military background [in the conservation field]. The big problem is that the wildlife organizations hate to be seen as militaristic. But people in the United States don’t understand the nasty people you’re dealing with. You have to deal with them in a like manner.”

That approach would come to define Kalron and Maisha even more in the coming months. Since they trained Dzanga-Sangha’s 70 or so rangers, anti-poaching measures seem to be succeeding. Tourists have continued returning to the park, Jean-Bernard Yarissem, World Wildlife Fund national coordinator for the CAR, would tell me.

But Kalron and his team have moved on to other hot spots across Africa. Today they are working closely with wildlife authorities in Uganda, the birthplace of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army, the messianic rebel cult, and also training anti-poaching dogs and rangers in northern Kenya, a frequent zone of conflict with Somalia’s al-Shabab terrorists. And Kalron has staff in Cameroon, near the Nigerian border, where the radical Islamist group Boko Haram is reportedly using profits from poaching to help fund its operations. “You name a hell hole with a rebel group, and we’re there,” Kalron says. The group’s application of counterterrorism methods to wildlife protection has also brought it full circle: Now it’s providing advice on intelligence regarding terrorist threats to governments in “both Europe and North America,” Kalron says—without going into detail. “They value us because of our experience in the Middle East and Africa.”

**********

After three days in Dzanga-Sangha, we climbed into another motorized pirogue for the long journey down the Sangha River to Ouesso, then by road to Brazzaville. The elephant rampage notwithstanding, there was a sense that things had gone well. The surveillance equipment in the Dzanga bai was in working order; the World Wildlife Fund had re-established a presence in the park; the forest elephants seemed out of danger, at least for the time being. Kalron had signed a contract to retrain Dzanga-Sangha’s rangers.

As we reached the outskirts of Brazzaville at 3 a.m., after a 22-hour journey, we pulled up to a roadblock manned by a police force that has a reputation for being corrupt. “Where are your papers?” a surly sergeant demanded, and Kalron, stepping out of the car, showed him passports and documents from the Wildlife Conservation Society, his sponsor in the Republic of Congo. The sergeant insisted that the team’s Congolese visas had expired. The policeman demanded hundreds of dollars in “fines”; Kalron refused. The two men faced each other on the deserted street in the run-down, humid Congolese capital. Kalron stayed calm, arguing that the officer had read the expiration date wrong, quietly refusing to turn over any money. After about an hour, the sergeant gave up and allowed us to pass.

Kalron guided us through the empty streets to the Conservation Society guesthouse, past three burned-out Jeeps and a house blasted by grenades and bullets—the residue of a feud between President Denis Sassou Nguesso and a rogue military officer a few months earlier. “We had front-row seats at the battle,” said Kalron, and if I’m not mistaken, he was smiling.

Related Reads

Ivory, Horn and Blood: Behind the Elephant and Rhinoceros Poaching Crisis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/08/b608d5c8-7444-4d30-8bd4-017a03b3e8bc/jun2016_a07_kalronspecialops.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)