Flower Power, Redefined

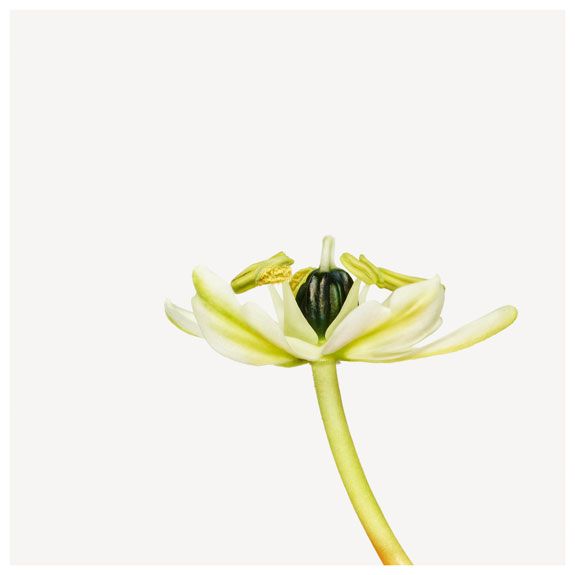

In a new book, Andrew Zuckerman embraces minimalism, capturing 150 colorful blooms on white backdrops

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121212091008Beehive-ginger-web.jpg)

With a stark white background and a splash of color, minimalist master Andrew Zuckerman has reinvented the way we look at the world around us. Known for his crisp photographs of celebrities and wildlife, Zuckerman turned his lens on the plant kingdom and captured 150 species in full bloom for his latest book Flower.

The filmmaker/photographer culled through over 300 species—even visiting the Smithsonian Institution— to select plants both familiar and exotic. Armed with a 65 mega-pixel camera, Zuckerman’s images capture the color, texture and form of each flower and showcase them in a way never seen before. Smithsonian.com’s multimedia producer, Ryan R. Reed, recently interviewed Zuckerman to find out more about Flower and the creative process behind the images.

You’ve shot portraits of politicians, artists and endangered species. Why did you decide to turn your camera on flowers?

I am very interested in the natural world, honestly not as a scientist or from any intellectual place, but from a visual perspective. I am really interested in this precise translation of the natural world. I like photography as a recording device. It’s the best possible two-dimensional representation of 3D living things that we have.

A project like Flower suits my tendencies. I have really wanted to understand how things work my whole life and then deconstruct things. My work—these books, these projects—are about being curious about a subject. When I want to understand a subject, I decide, okay, I’m going to focus on this for a year, and I go out and I do a lot of research and I find out a lot about the subject, in this case flowers. I partner with people who have flowers in private collections, and I decide to methodically go through it.

The flowers are photographed on stark white backgrounds. Why did you make this choice?

The work is not on white for an aesthetic reason. The flowers are on white because that is neutral; I sort of vacuum everything out. I find that you take a walk in nature and come upon an amazing flower, and that flower, your understanding of it, your interpretation of that experience seeing that flower, is chaotic and confused by everything around it. The weather, the green plants around it, the path you are on, a number of different variables that have very little to do with the flower are there. When I get interested in a subject, I am most interested in honing in and nailing down exactly what it is. So, in terms of a flower, I want to take it out of its context. I want to study its form.

I am not interested in Ted Kennedy in his office on Capitol Hill with his books and his beautiful desk and everything, his environment. I’m interested in him, his face, his expression. How do you reduce the subject down to its essential qualities, and then, furthermore, when you do a number of subjects, how do you democratize all of them so that you can see the differences between them? So that you are not seeing the differences between the white of the background or the light or anything else, but you are just seeing the subject. It seems simple, but for me it’s been a very challenging and exciting process to really find what it is that is truly essential to that singular subject, and then to see it in context of its family rather than the environment that it’s thriving in.

How did you select which flowers you would photograph?

Taking the pictures is the easy part. Getting the subjects and figuring out what I want to do and what will tell the story in the most holistic way is the hard part. I am a big book collector. I love books. For a long time, every time I saw books on flowers, I had just been buying them. I had been tagging pages of flowers.

Darwin’s star orchid, for instance, is not a particularly pretty flower. It’s not even a particularly interesting-looking flower, but the narrative of it is fascinating. It was totally instrumental in Darwin’s formulation of the theory of evolution. There is this 11-inch spur that is coming off of its blossom from the bottom, and he thought there has to be this insect with some kind of an appendage long enough to pollinate it. No one believed him, but 40 years later entomologists discovered this moth with a tongue that is four times longer than its body. It was the one insect that could unfurl its tongue, get all the way to the bottom past that spur and pollinate the flower.

Then, there is the purple passionflower, which is an incredibly beautiful, vibrant, flamboyant flower, but its narrative qualities are not that interesting to me. So, there were different reasons for different flowers. I wanted to touch on different types of flowers—medicinals, orchids, roses and other groups. For the most part, I have like a hit list, a real wish list, and I have been very fortunate to work with some serious, smart and efficient people here at the studio, who would be calling institutions and private collections and organizing when the perfect date was for a flower to be photographed. Getting an extraordinary place like the Smithsonian to allow me to just roll in and set up a studio in their greenhouses and have the pick of the place is an incredibly lucky thing.

Can you describe the setup for each flower and the techniques that you used?

It’s a numbers game; take as many shots as I can, and I’m going to get the one that I respond to most. Artists, especially, have anxiety…what is my vision? What is me, or is the thing I just did actually an expression of what I have seen? The work that I feel is most authentically mine is the one that is my first reaction, the first thing that feels like the truth. In aggregate, those choices, those series of decisions, create your point of view, your visual language. With Flower, I was searching for that project that I would not have to justify intellectually or think about in any way. That’s what was fun about it.

My set up is very simple. I’ve been doing my lighting and photographing things the exact same way for a very long time. Mapplethorpe contextualized flowers. Georgia O’Keeffe contextualized them. They’ve often been metaphors for something of the human condition. I was just interested in the flower; I wasn’t interested in the flower standing in for something else. And so, there’s a reason there are no shadows or romance in my work. I don’t place myself onto the image. I actually try to get myself out of the work so that one doesn’t look at the work and go “wow, that’s an amazing picture” but that someone looks at it and says “wow, that’s an incredible flower.” I’m sort of a conduit to get the information from the natural world to the viewer. The choices made in composition are purely instinctual, and I try to never go, is that right? I think, okay, I put it there, that feels right. As soon as it feels right, I move on; it’s very quick actually.

You produced videos in conjunction with the book. Can you talk about these?

I’d say a majority of my time is spent film making, not photographing, and every single project I’ve done has had a strong film component to it. I’m very interested in multiple entry points; I like houses with lots of doors. When I do a project, I like the idea that someone is going to experience the book, someone is going to experience the film, someone else is going to experience a framed photo on a wall, but they are all going to get to the same root thing as long as all of those mediums are exploring it from the same place.

It was just kind of fun. There’s this long history of time-lapse filmmaking of flowers, and I get especially excited about and challenged by exhausted subjects and mediums. I look at the time-lapse film and I go, is there anything else we can do with this? Is there anything that hasn’t been done yet? Can we breathe life into this? Because it’s not the subject we’re tired of, it’s the execution. So, is there another way to execute this?

I had the flowers around the clock in my studio for a couple of weeks at a time. I would take a singular photograph every five minutes, and then my friend Jesse Carmichael, who was a founder of Maroon Five, made this really interesting score.

Claire Tinsley, Smithsonian.com’s production intern, assisted in the production of this Q&A.