Fossil of Ancient Bird Three Times Bigger Than an Ostrich Found in Europe

The fossil is about 1.8 million years old, meaning the bird may have arrived on the continent around the same time as Homo erectus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/69/eb698f70-f2c7-4a20-99ee-9afd1bd8f95d/204234_web.jpg)

Giant birds of the past have names that speak for themselves. The elephant bird, a native of Madagascar and the largest known giant bird, stood at over nine feet tall and weighed in at a whopping 1,000 pounds or more, until it went extinct about 1,000 years ago. Australia’s mihirung, nicknamed “thunder bird,” which disappeared nearly 50,000 years ago, is thought to have been nearly seven feet tall and weighed between 500 and 1,000 pounds. But until now, no one had ever found evidence of these towering avians in Europe.

Today, researchers describe the first fossil of a giant bird found in Crimea in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Dated at around 1.8 million years old, the specimen makes experts question previous assumptions that giant birds were not part of the region’s fauna when early human ancestors first arrived in Europe.

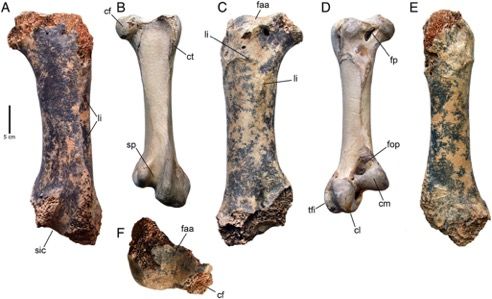

A team of paleontologists dug up the fossil—an unusually large femur—in Taurida Cave, located on the Crimean Peninsula in the northern Black Sea. The cave was only discovered last June when the construction of a new highway revealed its entrance. Initial expeditions last summer led to exciting finds, including the bones and teeth of extinct mammoth relatives. Of course, the team didn’t expect to find large birds, since there had never been evidence of their existence in Europe.

“When these bones reached me, I felt like I was holding something belonging to elephant birds from Madagascar,” paleontologist Nikita Zelenkov of the Borissiak Paleontological Institute, who lead the study, says in an email. “This was the most surprising [part] for me, such an incredible size. We did not expect [that].”

Based on the femur’s dimensions, the team calculated that the bird would have weighed around 992 pounds—as much as an adult polar bear—making it the third largest bird ever recorded.

Although the bone was similar in size to an elephant bird’s femur, it was more slender and elongated, like a larger version of the modern ostrich (Struthio camelus). “The main difference from Struthio is the notable robustness. There are also some less visible details, like the shape or orientation of particular surfaces, which indicate a different morphology from ostriches,” Zelenkov says.

Based on these distinctions, the team tentatively classified the femur as belonging to the flightless giant bird Pachystruthio dmanisensis. A similar-looking femur from the Early Pleistocene was found in Georgia and described in 1990, but at the time, the team didn’t calculate the full size of the ancient bird.

The femur’s shape also gives us clues about what the world was like when Pachystruthio was alive. Its similarities to the bones of a modern ostrich suggest that enormous bird was a good runner, which could imply that it lived among large carnivorous mammals like the giant cheetah or saber-toothed cats. This idea is supported by the earlier findings of nearby bones and fossils.

Additionally, Pachystruthio’s immense mass could point to a drier, harsher environment. Previous studies of Australia’s mihirung suggest that it evolved to be a larger size as the landscape became more arid, since a larger body mass can digest tougher, low-nutrition food more efficiently. Pachystruthio may have evolved its large stature for similar reasons.

Perhaps most notably, the team hypothesizes that Pachystruthio was present when Homo erectus arrived in Europe during the Early Pleistocene and possibly arrived via the same route. Knowing that the two ancient species could have coexisted introduces a world of new questions for scientists.

“The thought that some of the largest birds to have ever existed were not found in Europe until so recently is revelatory,” Daniel Field, a paleobiologist at the University of Cambridge who was not involved in the new research, says in an email. “[It] raises exciting questions about the factors that gave rise to these giant birds, and the factors that drove them to extinction. Was their disappearance related to the arrival of human relatives in Europe?”

Delphine Angst, a paleobiologist at the University of Bristol who was also not involved in the study, says it’s too early to tell without direct evidence of human life near the same site. “For this specific case, it’s difficult to answer,” Angst says. “But if you take all the examples we have, like the moas in New Zealand, we have plenty of clear evidence that these birds were hunted by humans. It’s completely possible in the future that we will maybe find some evidence, like bones with cutting traces or eggshells with decorations. There’s no information yet for this specific case, but it’s possible.”

Despite the lack of a definitive answer, Angst emphasizes that this is an important step toward understanding how these birds evolved and later went extinct.

“These giant birds are known in various places in the world for different periods of time, so they’re a very interesting biological group to understand how an environment works,” Angst says. “Here we have one more specimen and one more giant bird in one more location. … Any new piece is very important to helping us understand the global question.”

As the fossil’s discovery continues to challenge previous ideas, it’s clear that unlike Pachystruthio, this new finding is taking flight.