Fruits and Veggies Get a Close-Up

In the darkroom, photographer Ajay Malghan creates abstract art by casting light through thin slices of produce

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/92/7392cdf1-7bb1-4844-bb46-b37edfa0f15b/ajay-malghan-naturally-modified-broccoli.jpg)

One spring semester, Ajay Malghan was experimenting in the dark room at Savannah College of Art and Design’s Hong Kong campus, where he was earning his MFA in photography. He used watercolor on glass plates. He bleached film. He painted lettuce, until finally, he struck an idea he felt was worth pursuing—slicing thin cross sections of fruits and vegetables.

Take a strawberry, for example. From the widest part of the berry, Malghan extracted a thin layer. He laid the fruit outside in the sun and, when it was dry, placed it between two 8-by-10-inch pieces of glass he purchased at Home Depot. In the darkroom, he then projected an image of the strawberry onto light-sensitive paper by shining a magenta light through the cross section.

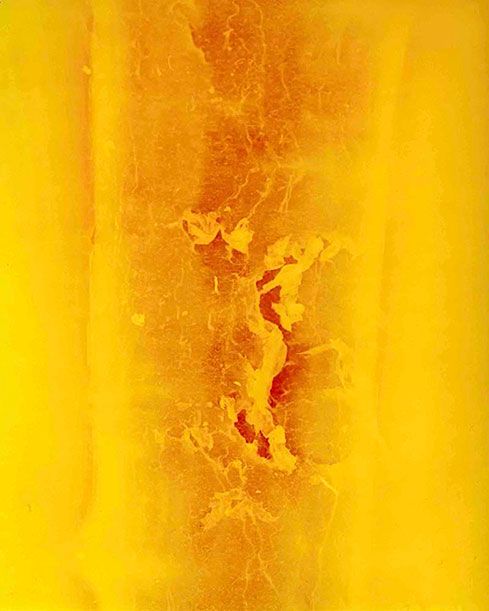

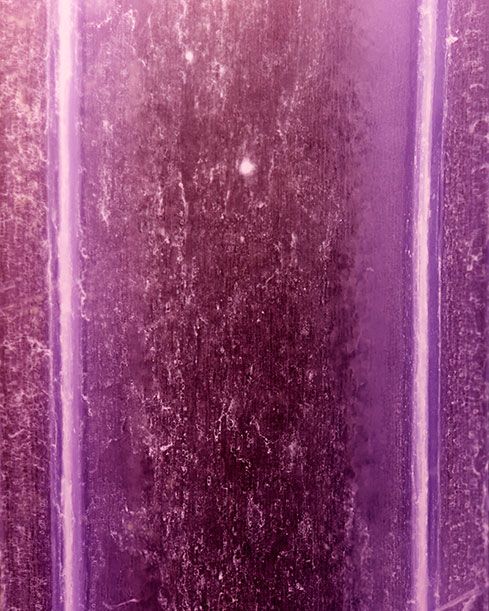

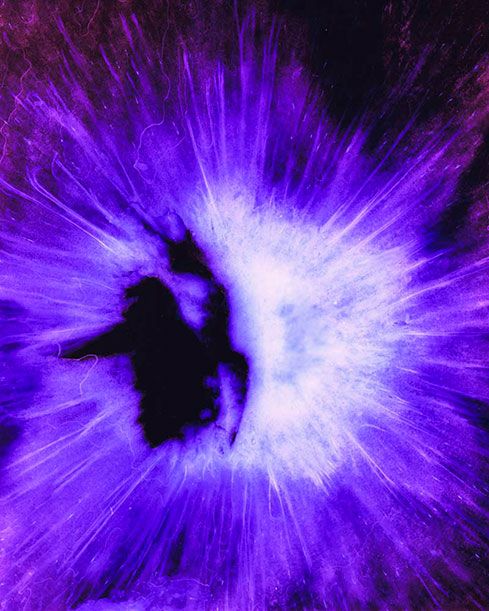

Malghan has applied this same technique, using cyan and yellow lights as well, to other foods–carrots, broccoli, oranges, watermelon, onions, celery, apples, peaches, lemons, potatoes and tomatoes–”whatever I can slice without it falling apart,” he says. The result is a series of abstract close-ups, brilliantly colored and befuddling, that the photographer calls Naturally Modified. See if you can guess what’s here–answers are at the end of the post.

In the beginning, Malghan intended for the project to be a commentary on genetically modified foods, calling attention to all the engineering and processing involved in the agriculture industry. The series’ title, Naturally Modified, is a remark on how the photographer alters the produce, naturally, with light and color. Now, he calls that stance a “rookie mistake made in vain,” admitting that it was just something to write about for his thesis.

“Over time, I’ve understood the work is about multiple things—light, color, nature, complexity, the abstract—but the underlying theme is about asking questions and opening doors rather than making declarative statements,” he says.

Watermelon and tomato are the trickiest of subjects, Malghan reports. With so much water, they are frustrating to slice. “In hindsight, I should have frozen them or bought a mandolin ,” he says. Bananas are clumsy as well; the photographer ultimately abandoned the actual banana, making use of its peel instead.

The photographer has his sights set on trying the technique on other produce. He picked up a lotus root in New York’s Chinatown this past winter and meant to try it. “I think the skins of certain fruits and vegetables would be interesting,” he adds. “I’m curious as to what various bell peppers or apple skin may look like.”

After scanning his darkroom images at a high resolution, Malghan prints them on a large scale, typically 30-by-40 inches. “We usually possess these fruits and vegetables in our hands or on plates and in bowls, so seeing them larger removes them from their usual context,” he says. He also chooses not to identify his subjects with image titles. ”We have enough information at our fingertips these days, so I thought it would engage more conversations leaving the labels out,” he adds.

The decision to leave the images open to viewers’ interpretation has proven to be—well, fruitful. “One woman in Hong Kong thought the image was of people dancing,” Malghan says. “That thought may not have occurred if I labeled it Orange_3.”

Answers: 1) broccoli 2) carrot 3) celery 4) pear 5) persimmon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)