My dear Girl:

In the first place will you allow me to suggest that you forget

hereafter to tack the "ess" on to "author", because one who writes

a book or poem is an author and literature has no sex.

–Gene Stratton-Porter, letter to Miss Mabel Anderson, March 9, 1923

* * *

Yellow sprays of prairie dock bob overhead in the September morning light. More than ten feet tall, with a central taproot reaching even deeper underground, this plant, with its elephant-ear leaves the texture of sandpaper, makes me feel tipsy and small, like Alice in Wonderland.

I am walking on a trail in a part of northeast Indiana that in the 19th century was impenetrable swamp and forest, a wilderness of some 13,000 acres called the Limberlost. Nobody knows the true origin of the name. Some say an agile man known as “Limber” Jim Corbus once got lost there. He either returned alive or died in the quicksand and quagmires, depending which version you hear.

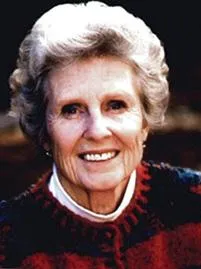

Today, a piece of the old Limberlost survives in the Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve, 465 acres of restored swampland in the midst of Indiana’s endless industrial corn and soybean fields. It’s not obvious to the naked eye, but life here is imitating art imitating life. The artist was Gene Stratton-Porter, an intrepid naturalist, novelist, photographer and movie producer who described and dramatized the Limberlost over and over, and so, even a century after her death, served as a catalyst for saving this portion of it.

As famous in the early 1900s as J.K. Rowling is now, Stratton-Porter published 26 books: novels, nature studies, poetry collections and children’s books. Only 55 books published between 1895 and 1945 sold upwards of one million copies. Gene Stratton-Porter wrote five of those books—far more than any other author of her time. Nine of her novels were made into films, five by Gene Stratton-Porter Productions, one of the first movie and production companies owned by a woman. “She did things wives of wealthy bankers just did not do,” says Katherine Gould, curator of cultural history at the Indiana State Museum.

Her natural settings, wholesome themes and strong lead characters fulfilled the public’s desires to connect with nature and give children positive role models. She wrote at a pivotal point in American history. The frontier was fading. Small agrarian communities were turning into industrial centers connected by railroads. By the time she moved to the area, in 1888, this unique watery wilderness was disappearing because of the Swamp Act of 1850, which had granted “worthless” government-owned wetlands to those who drained them. Settlers took the land for timber, farming and the rich deposits of oil and natural gas. Stratton-Porter spent her life capturing the landscape before, in her words, it was “shorn, branded and tamed.” Her impact on conservation was later compared to President Theodore Roosevelt’s.

In 1996, conservation groups, including the Limberlost Swamp Remembered Project and Friends of the Limberlost, began buying land in the area from farmers to restore the wetlands. Drainage tiles were removed. Water returned. And with the water came the plants and bird life Stratton-Porter had described.

One of the movement’s leaders, Ken Brunswick, remembered reading Stratton-Porter’s What I Have Done With Birds when he was young—a vibrant 1907 nature study that reads like an adventure novel. At a time when most bird studies and illustrations were based on dead, stuffed specimens, Stratton-Porter mucked through the Limberlost in her swamp outfit in search of birds and nests to photograph:

A picture of a Dove that does not make that bird appear tender and loving, is a false reproduction. If a study of a Jay does not prove the fact that it is quarrelsome and obtrusive it is useless, no matter how fine the pose or portrayal of markings....A Dusky Falcon is beautiful and most intelligent, but who is going to believe it if you illustrate the statement with a sullen, sleepy bird?

Now, birds once again chorus at the Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve, which is owned by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources. Curt Burnette, a naturalist with the site, calls out, “Sedges have edges, rushes are round, and grasses are hollow from top to the ground!” A dozen of us follow him along paths through the prairie grass. He stops to identify wildflowers. Here’s beggar’s-ticks. Taste the mountain mint. Growing at your feet is partridge-pea. Pokeweed, bottle gentian, white false indigo. That mauve flower? Bull thistle.

Dragonflies and damselflies hover. Salamanders and snakes are around. I think of Stratton-Porter in her waist-high waders.

* * *

Geneva Grace Stratton, who was born on Hopewell Farm in Wabash County, Indiana, in 1863, the youngest of 12 children, described her childhood as one “lived out-of-doors with the wild almost entirely.” In her 1919 book Homing With the Birds she recalled a dramatic childhood encounter. She was climbing a catalpa tree in search of robins’ nests when she heard a blast from her father’s rifle. She watched a red-tailed hawk tumble from the sky. Before he could lift his weapon again, young Geneva bolted along a path and flew between bird and gun. Horrified that he could have shot his daughter, Mark Stratton pulled up the weapon.

Bleeding and broken, the hawk, she recalled, looked up at her “in commingled pain, fear, and regal defiance that drove me out of my senses.” They transported it to a barn where Geneva cleaned its wounds and nursed it back to health. It never flew again, but it followed her around the farm like a dog, plaintively calling to other hawks overhead.

Her family gave her the name “Little Bird Woman.”

Not long after, her father, an ordained minister, formally presented Geneva with “the personal and indisputable ownership of each bird of every description that made its home on his land.” She embraced the guardianship with joyful purpose, becoming the protector of 60 nests. A blood-red tanager nesting in a willow. Pewees in a nest under the pigpen roof. Green warblers in sweetbriar bushes. Bluebirds, sparrows and robins. Hummingbirds, wrens and orioles.

Making her rounds, Geneva learned patience and empathy: approaching nests slowly; imitating bird calls; searching bushes for bugs; bearing gifts of berries, grains and worms. She earned the confidence of brooding mothers enough to touch them. She remembered how “warblers, phoebes, sparrows, and finches swarmed all over me, perching indiscriminately on my head, shoulders, and hands, while I stood beside their nests, feeding their young.”

Shortly before her mother died of complications from typhoid, the family moved to the town of Wabash, where at age 11, Geneva—fussing about having to wear proper dresses and shoes—began attending school. Adjusting to life without her mother and her farm was difficult. Geneva insisted on transporting her feathered charges—nine in total, injured or abandoned—to school in cages.

When Geneva was 21, Charles Dorwin Porter—a businessman known as one of the most eligible bachelors in the Decatur area—spotted the lively, gray-eyed brunette at a social event on Sylvan Lake. He was 13 years her senior, and his first letter of courtship, in September 1884, arrived as formal as a starched shirt: “Having been rather favourably impressed with your appearance, I venture the forwardness to address you.”

Charles and Gene, as he affectionately called Geneva, exchanged long and increasingly warm handwritten letters. Several months and kisses later, she was “Genie Baby.” In a letter to Charles composed a year after they met, she informed him of her position on a subject of growing interest to him.

You have ‘concluded that I favour matrimony.’ Well, so I do, for the men. I regard the pure and lovable wife as the best safeguard for a man’s honour and purity; the comfortable and happy home as his rightful and natural resting place; and every loving environment that springs from such a tie one step nearer the heart of earth’s dearest and best. That’s for the man. And for every such home some woman is the sacrificial flame that feeds the altar. I take notice that my girl friends who have been engaged a year and those who have been married a year look vastly different, and it sets me to pondering on the differences between a man’s engaged love and his married love.

In April 1886, wearing a silk gown with a pink taffeta brocade of rosebuds and soft green leaves, an ostrich plume in her hat, she was married in Wabash. She had let go of her doubts about marriage, but retained her pluck and her own pursuits. When most women were homemakers, Stratton-Porter created a double-barreled life, in name and in career, with the support of her husband.

In 1888, they moved with their only child, Jeannette, from Decatur to a nearby town that coincidentally shared her name, Geneva. During the oil boom of the 1890s, the town grew to boast seven taverns and seven brothels. As a young mother in this small town, Stratton-Porter enjoyed domestic life. She painted china. She embroidered. She designed their new home, the Limberlost cabin. She tended plants in her conservatory and garden.

She also carried a gun and wore khaki breeches into the snake-filled Limberlost swamps less than a mile away from her home in search of wildflowers, moths, butterflies and birds. She voted on the board of directors at Charles’ Bank of Geneva.

One night, Stratton-Porter also helped rescue downtown Geneva. It was 1895 and Charles was away on business. Hearing screams, Stratton-Porter pulled a skirt over her nightgown and, long hair flying, ran into the melee of onlookers. Flames engulfed Line Street. There was no local fire brigade, and no one was taking charge. Stratton-Porter organized people and water and battled until cinders singed her slippers and heat blistered her hands. The drugstore Charles owned was destroyed in the fire, but she saved the Shamrock Hotel building, which also belonged to her husband and housed the bank he owned. The local newspaper said Stratton-Porter “would make an energetic chief of the fire department when that needed improvement is added to our village.”

* * *

“Look! A bald eagle!” a woman in our group shouts. There it is. White tail, white head, the unmistakable eagle circles overhead. It reminds me that the Limberlost now is not the Limberlost Stratton-Porter knew. Back in her day, says Burnette, the bald eagles “were all extirpated,” as were deer, otter, beaver and wild turkey. They have since rebounded.

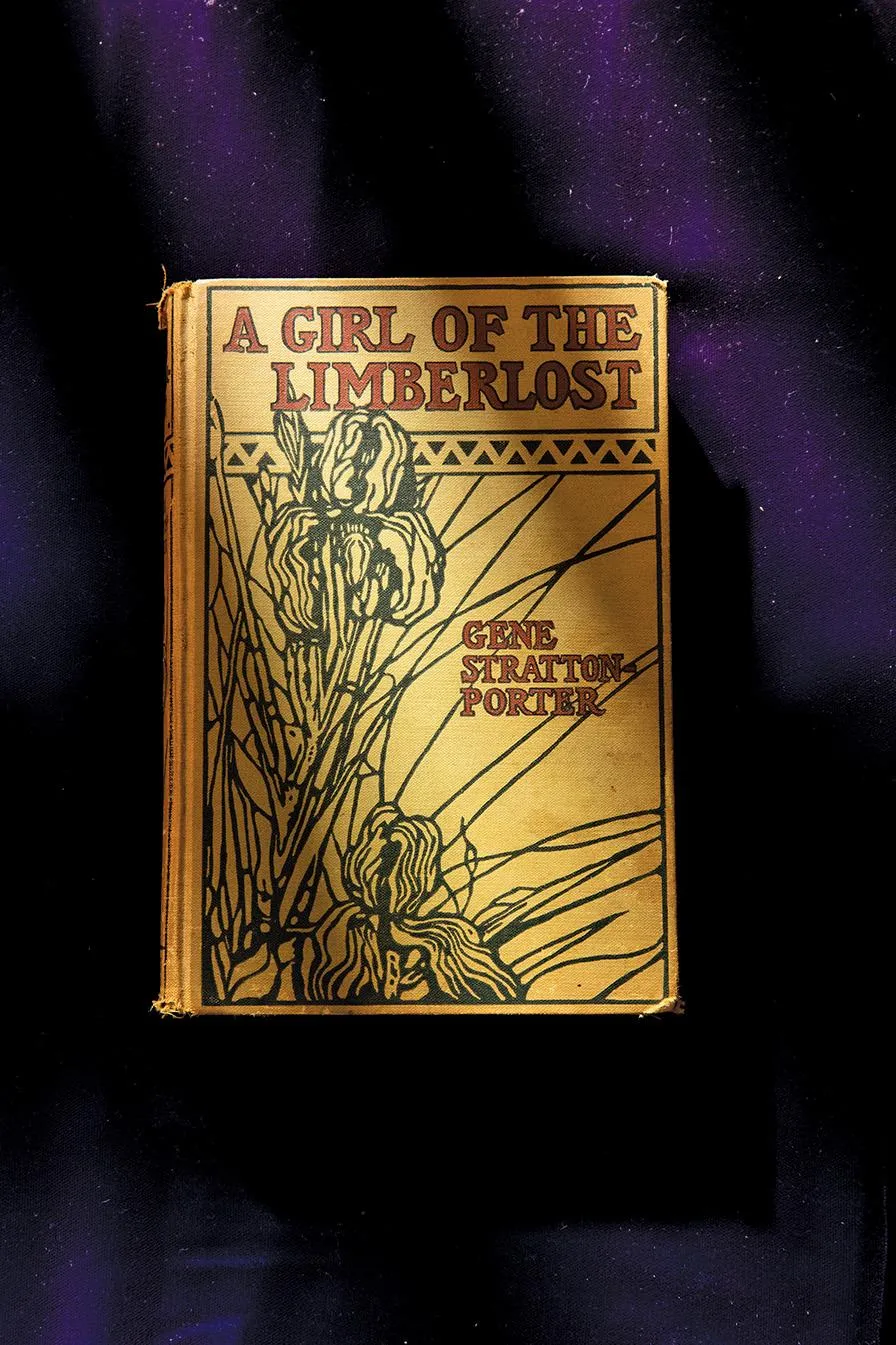

In 2009, to mark the 100th anniversary of A Girl of the Limberlost, a beloved novel about a young Hoosier named Elnora who collects moths, the Loblolly Marsh carried out a 24-hour biodiversity survey. Volunteers recorded 545 species: two bees, 55 birds, 29 dragonflies and damselflies, 24 moths and butterflies, one fish, 25 fungi, 15 reptiles and amphibians, two insects, five mammals, 376 plants, and 11 sciomyzid flies. Some of those life-forms have rebounded even further—but not the moths and butterflies Stratton-Porter loved so well. Their losses are staggering here, a part of the rapid decline of biodiversity driven by humans.

In 1900, Stratton-Porter’s article “A New Experience in Millinery,” published in Recreation, called attention to the slaughter of birds for ladies’ hats. “All my life I have worn birds and parts of birds as hat decorations and have given the matter no thought,” she wrote. “Had I thought on the subject I should have reformed long ago, for no one appreciates the beauty of the birds, the joy of their songs or the study of their habits more than I do.”

After a number of successful magazine stories came the book deals. Her 1904 novel Freckles was about a one-handed ragamuffin Irish boy. Freckles found work walking a seven-mile circuit to patrol a valuable area of lumber against maple thieves. Stratton-Porter struck a deal with Doubleday, her publisher, to alternate between nonfiction nature studies and sentimental stories with happy endings and heavy doses of nature. Her romances were enjoyably escapist and her independent female characters offered millions of girls and women alternative life narratives.

After her husband and daughter gave her a camera for Christmas in 1895, Stratton-Porter had also become an exceptional wildlife photographer, though her darkroom was a bathroom: a cast iron tub, turkey platters, and towels stuffed under the door to keep out light.

Her photographs are detailed, beautifully composed and tender, as if there is a calm understanding between bird and woman. Birds clearly trusted her, allowing Stratton-Porter to capture never-before-seen details of cardinals fluffing after a bath, kingfishers perched on a tree stump in the sun, bluebirds feeding their young, and more. “Few books entail such actual labor as this, such marvelous patience,” a New York Times reviewer wrote of What I Have Done With Birds, “and few books are produced with a spirit of enthusiastic at-oneness with the subjects.”

Porter was keenly aware of how her approach differed from others’. “I often find ornithologists killing and dissecting birds, botanists uprooting and classifying flowers, and lepidopterists running pins through moths yet struggling,” she wrote in her 1910 book, Music of the Wild/With Reproductions of the Performers, Their Instruments and Festival Halls. She went on, “Whenever I come across a scientist plying his trade I am always so happy and content to be merely a nature-lover, satisfied with what I can see, hear, and record with my cameras.”

Her work was featured in the magazine American Annual of Photography for many years and she earned the highest prices ever paid for bird pictures. “Had she not been a woman, entirely self-trained,” Jan Dearmin Finney writes in The Natural Wonder: Surviving Photographs of the Great Limberlost Swamp by Gene Stratton-Porter, “her work might have been taken more seriously by her contemporaries.”

* * *

I arrange to meet Curt Burnette at the Rainbow Bottom, 270 acres of hardwood forest owned by the Friends of the Limberlost. We walk along a wooded path of cracked mud imprinted with deer and raccoon tracks until we come to a ten-foot-wide double-trunked sycamore that looks like a giant wishbone jutting upward. Blue herons fly overhead and orange monarch butterflies drink from pink false dragonhead in a lush meadow. Farther on, we find a tree fallen across an old channel of the Wabash and sit.

“To me,” Burnette says, thoughtfully, “this is the spot in the Limberlost where modern life disappears.”

In the verdant canopy, chatters and trills of chickadees, flycatchers and phoebes rain down around us. A cranky white-breasted nuthatch spots us in its territory and makes displeasured staccato chirps as it madly descends a hickory tree. I slide my camera phone out of my back pocket and snap a quiet picture. The ease of this motion contrasts sharply with the daunting lengths Stratton-Porter went to do the same: maneuvering her horse, rigging heavy cameras in trees with ropes, sidestepping quicksand and rattlers, directing assistants, scaling ladders to replace each glass film plate, and waiting. There was a lot of waiting—sometimes a week for one shot.

For seven years Stratton-Porter delved into everything moth-related, and this influenced not only her novel A Girl of the Limberlost—the teenage Elnora and her widowed mother emerge from metaphorical cocoons to become their better selves—but also her nonfiction Moths of the Limberlost, which included reproductions of her painstakingly hand-colored photographs. “Her observations are scientifically valuable, her narrative is entertaining, her enthusiasm catching, and her revelations so stimulating that one readily forgives some minor defects in bookmaking,” said a review in the New York Times. (Today, dozens of her moths and butterflies are on display at her old Limberlost cabin, including a spicebush swallowtail butterfly, a red admiral and an io moth suspended in flight.)

Twenty years before the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Stratton-Porter forewarned that rainfall would be affected by the destruction of forests and swamps. Conservationists such as John Muir had linked deforestation to erosion, but she linked it to climate change:

It was Thoreau who in writing of the destruction of the forests exclaimed, ‘Thank heaven they cannot cut down the clouds.’ Aye, but they can!...If men in their greed cut forests that preserve and distill moisture, clear fields, take the shelter of trees from creeks and rivers until they evaporate, and drain the water from swamps so that they can be cleared and cultivated, they prevent vapor from rising. And if it does not rise, it cannot fall. Man can change and is changing the forces of nature. Man can cut down the clouds.

Writing nature studies stirred Stratton-Porter’s soul, but her fiction, she felt, inspired people to higher ideals. She paid little attention to the literary establishment when it criticized her novels for having saccharine plots and unrealistic characters. She insisted that her characters were drawn from genuine Indiana folks. Unlike her contemporary Edith Wharton, she once wrote,“I could not write of society, because I know just enough about it to know that the more I know, the less I wish to know.”

At the same time, despite all her rustic pursuits, Stratton-Porter, like Wharton, was no stranger to the prerogatives of wealth, both hers (from book sales) and her husband’s. Ironically, perhaps, while she was writing about the disappearance of the Limberlost, Charles was adding to his fortune selling oil from 60 wells on his farm.

Speaking Out

In 1919, Stratton-Porter moved to Southern California.* She’d been unhappy with the film adaptations of her novels, and she established Gene Stratton-Porter Productions to control the process herself. She built a vacation home on Catalina Island and started building a mansion in the area that’s now Bel Air.

In her extensive career, the most puzzling and most damaging thing she created was the racist theme of her 1921 novel Her Father’s Daughter. The heroine, a high-school student named Linda, makes derogatory remarks about a Japanese classmate who is on track to become valedictorian. (The brilliant Asian student is later revealed to be a man in his 30s who is posing as a teenager.) “People have talked about the ‘yellow peril’ till it’s got to be a meaningless phrase,” Linda says. “Somebody must wake up to the realization that it’s the deadliest peril that has ever menaced white civilization.”

Did these views belong solely to Stratton-Porter’s fictional characters, mirroring the racist sentiment that would give rise to Japanese-American internment camps in the 1940s? Or were these Stratton-Porter’s own views? No Stratton-Porter scholar I spoke with was able to definitively answer this question, and none of the many letters of hers I read offered any clues. Her Father’s Daughter is a disturbing read today.

Stratton-Porter’s next book, The Keeper of the Bees, was more in line with her earlier work—a novel about a veteran of the Great War who healed his spirit by becoming a beekeeper. It appeared serially in McCall’s, but she did not live to see it published as a book: She was killed in Los Angeles on December 6, 1924, when her chauffeured Lincoln was struck by a streetcar. She was 61.

Her London Times obituary noted that she was “one of the small group of writers whose success, both in England and in America, was enormous. She was one of the real ‘big sellers,’ her novels being eagerly read and re-read by all sorts and conditions of people, children and adults. It is rare indeed for a writer to appeal, as she did, both to experienced readers equipped with standards of literary taste and to the most unsophisticated, who live apart from the world of books.”

Porter was such a beloved author that New York State commemorated her with a grove of 10,000 trees along Lake George. During “Gene Stratton-Porter Memorial Week,” programs across the country celebrated the literature and landscapes that were her legacy.

But the greatest tribute to her by far is the Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve. In the grass on the side of the road there, I see a rusty horseshoe from a passing Amish buggy, cast off like a message from another era. I reach down, pick it up, and pop it into the back pocket of my jeans like a lucky charm. I will hang it above my greenhouse door in England.

I walk through the wildflower meadow and skirt the pond. I am on the lookout for blue grosbeak, kingbirds and maybe pelicans. Instead, a red-spotted purple butterfly sails through the air followed by an orange viceroy, bouncing over autumn goldenrod and purple thistle. In a landscape that has been erased, rewritten and restored, Gene Stratton-Porter’s handwriting is everywhere.

*Editor’s note, February 21, 2020: An earlier version of this story said that Stratton-Porter moved to Southern California with her husband in 1919. In fact, she moved without him.

:focal(275x225:276x226)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/80/51/80519042-65a8-4fe6-959e-a0e535153437/opener_mobile_600x350.jpg)

:focal(771x266:772x267)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/41/7f412cb1-92cc-49bd-8f11-a1a99d34f168/opener_2000x675.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/19/3819345c-671c-4978-834e-6e7badf99c65/mar2020_g22_genestrattonporter.jpg)