When Science Means Getting Cobra Venom Spat Into Your Eye

How a reptile mix-up and a fortuitous dose of breastmilk helped researchers tap into biodiversity in Africa’s eastern Congo

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/5f/ef5f5a99-8f05-4141-90ba-e0f683ec29fb/_eli0112-wr.jpg)

There was a snake in the basket, one of the men from Kamanyola told us. We watched in silence as he placed the basket carefully in the middle of the courtyard, lifted the lid, and scurried back several steps.

When nothing emerged, my herpetologist colleague Chifundera Kusamba inched up to it and peered over the top. “Oh, it’s a Psammophis,” he said. I was immediately relieved—and excited. Commonly known as sand snakes, Psammophis are common in the nonforested habitats of Africa and even range into Asia via the Arabian Peninsula. Although they have fangs in the rear of their mouth for subduing prey, the venom is too weak to harm humans.

Because Central Africa’s sand snakes, like most of its other snakes, are poorly known, I was hoping to get a fresh specimen and DNA sample to help unlock its evolutionary secrets. We'd seen a few of the sand snakes crossing the roads. But they are as fast as lightning, meaning one has zero chance of chasing them down unless they are cornered. Perhaps, I thought, the men from Kamanyola had worked in a team to do just that.

My Congolese colleagues—herpetologists Chifundera, Wandege Muninga, Maurice Luhumyo, and Mwenebatu M. Aristote—and I had set up our laboratory in the relatively arid region north of Lake Tanganyika, in search of just such rare snakes. Our goal was to improve researchers' understanding of eastern Congo’s poorly known herpetological diversity. In Africa’s Democratic Republic of the Congo, a nasty trifecta of crumbling infrastructure, gruesome tropical diseases and active militia have discouraged scientific expeditions since the violent end of colonialism in 1960.

Our expedition, it seemed, was off to a promising start. Curious to see what species this snake might be, I confidently walked up to the basket, looked inside—and felt my heart skip a beat. Chifundera’s preliminary impression, I realized, had been horribly wrong. Instead of seeing a Psammophis—a striped snake with a pointy snout—I saw a dull brown snake with a distinct round head raised a few inches off the ground. These physical traits all pointed to one group of dangerous serpents: cobras.

“It’s a cobra, watch out!” I yelled. In French I told my colleagues and bystanders to be careful, and mimicked the motion of spitting. I feared this could be a black-necked spitting cobra, which has the ability to spray venom into the eyes of its enemies, blinding them. Wandege looked at me and said, “Ndiyo!” (Yes!), because he and Maurice had surely encountered this species before.

The serpent in front of us belonged to an ancient lineage of highly venomous snakes. Called elapids, these include the New World coral snakes, African mambas, African and Asian cobras, Asian kraits, tropical ocean sea snakes and the highly venomous snakes that make their home in Australia. Unlike vipers, these snakes—which range in size from about 2 feet to the 19-foot-long king cobra of Asia—have long, muscular bodies that propel them rapidly and a lethally erect fang on their upper jaws.

Cobras also have prominent eyes that easily detect movement and elongated ribs at the front of their body, which are extended to stretch the skin of their necks forward and to the side to display the warning “hood” to would-be predators. Zookeepers who work with them describe them as belligerent, nervous and intelligent—a nasty and dangerous combination. Moreover, some African and Asian cobras have the ability to “spit” their painful and potentially blinding venom into the eyes of predators who do not take the hint from the hood warning.

Spitting cobras probably got their evolutionary start in Asia, where the defense would have given snakes an edge over predators like monkeys and human ancestors, suggests herpetologist Harry Greene. In Africa, the evolution of spitting seems to coincide with cooler climatic shifts starting about 15 million years ago that created more “open” habitats of grasslands, and later, even drier habitats with less vegetation. Because the snakes could not hide or escape from predators as easily in these habitats, spitting likely evolved as a much-needed defense.

In spitting cobras, the fangs have spiral grooves inside them that act like riflings in a gun barrel to force a spin on ejected venom. The opening of the fang is modified into a smaller, circular, and beveled aperture for more accuracy as muscles squeeze the venom gland and eject venom toward the threat. In other words: This is not a snake you want to meet in a dark alley—or a basket.

Fearless, Maurice confronted the basket and dumped the animal onto the ground. Everyone froze as the experienced snakeman used his favorite stick to pin the cobra to the ground behind the head. It wiggled its body as it tried to pull away, but Maurice knew from decades of experience just the right amount of pressure to apply to keep it where he wanted it without injuring it.

With his free hand, he slowly wrapped his fingers around the base of the cobra’s head and, releasing his stick, picked up the snake with his hands. Wandege rushed to his mentor to help him stabilize the snake’s body as it thrashed around in protest of its capture. Then, seeing that Maurice had firm control of the animal, the rest of us began to relax.

And then it happened.

As Wandege was holding the tail of the serpent, it managed to open its mouth and squeezed a jet of venom directly into his eye. He immediately dropped the snake’s tail, and wheeled around toward me. He didn’t say a word, but I knew what had happened from the look of horror in his eyes. The venom of spitting cobras is designed to be painful so that would-be predators cannot continue an attack.

I quickly grabbed a squeeze bottle I used for cleaning my tools for DNA samples and squirted a steady jet of water into his eye. I told him to move the eye around as much as he could as I worked the water onto as much of his eyeball as possible. As I ran into my room to look for painkillers and ibuprofen, Maurice managed to wrestle the snake safely into a cloth bag.

Wandege never whimpered, but it was obvious to everyone that he was in a great deal of pain.

I later found out that, after I had left, Chifundera had grabbed Wandege and found the nearest woman with a young child. She was nursing. This was important, because the cobra’s venom can be neutralized with milk. The woman allowed Wandege to rest his head on her lap and, putting her modesty aside, positioned her nipple over his head and squeezed until the precious antidote filled his excruciating eye. Thanks to the quick actions of this young mother, Wandege averted a potentially serious medical disaster.

Feeling terribly guilty about what had happened to my employee, I checked in on him every 15 minutes for the rest of the day to see how he was doing. We were too far away from a competent hospital to do anything more for Wandege that night, but he accepted my offer of painkillers, which seemed to ease his agony. Fortunately, he made a full recovery a few days later, and we all learned a hard lesson from his brief lapse of concentration.

In the end, the cobra specimen proved to be invaluable. It was the first specimen to be collected with muscle tissue (for DNA-based analyses) from eastern Congo. Genetic data generated from that sample were combined with several others from different areas of Africa to test whether the particular subspecies known from eastern Congo (Naja nigricollis crawshayi) is distinct from other populations in Africa. In the case of venomous snakes, an accurate understanding of their taxonomy is important to develop antivenom treatments for snakebite victims—or for those who have the misfortune of taking a spray of venom into their eyes.

This story is just a part of our larger ecological project: to bring attention to Congo’s treasure trove of biodiversity, where more conservation action is urgently needed. Since that encounter, my Congolese colleagues and I have published 28 peer-reviewed papers on biodiversity in Central Africa, and described 18 species that are new to science. Several of these are found in the Albertine Rift, a mountainous region that is considered one of the most significant biological hotspots in the world. It is also extremely fragile, because there is a high density of humans and a lack of law enforcement that allows people to destroy the environment with impunity.

Best of all, I am pleased to report that since our expedition, no other researchers in the region have been sprayed with snake venom in the name of science.

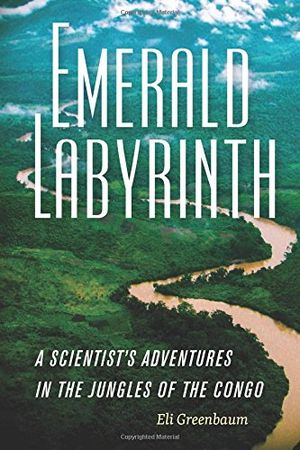

Editor’s Note: This excerpt has been adapted from the book Emerald Labyrinth: A Scientist's Adventures in the Jungles of the Congo by Eli Greenbaum.

Emerald Labyrinth: A Scientist's Adventures in the Jungles of the Congo

Emerald Labyrinth is a scientist and adventurer’s chronicle of years exploring the rainforests of sub-Saharan Africa.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.