In “The Glass Universe,” Dava Sobel Brings the Women ‘Computers’ of Harvard Observatory to Light

Women are at the center of a new book that delights not in isolated genius, but in collaboration and cooperation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/35/56353f6c-56a4-419e-8cdb-fa4387b642a4/unspecified-1.jpg)

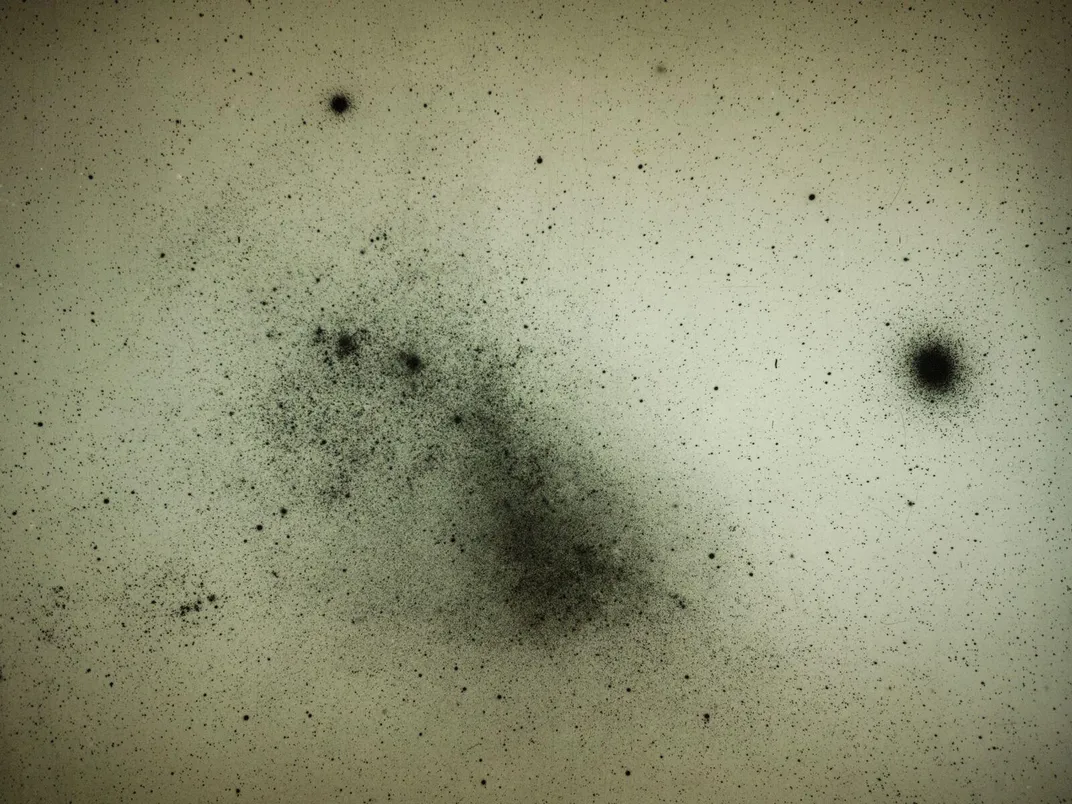

The Harvard College Observatory is home to over 500,000 glass photographic plates emblazoned with some of the most beautiful phenomena of our universe—star clusters, galaxies, novae, and nebulae. These plates are so scientifically and historically valuable that the Harvard Library is working to digitize them today. In her recent book The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars (out December 6), Dava Sobel tells the story behind of these plates and the group of women who dedicated their lives to studying and interpreting the mysteries hidden in them.

The process of making Harvard College Observatory the center of stellar photometry and discovery began in 1883, when Edward Pickering, the Observatory’s director, wrote to a woman named Mrs. Anna Palmer Draper. Pickering informed Mrs. Draper of his intent to carry out the work of her late husband Henry Draper—that of photographing the stars and determining their spectral classification. As director, Pickering already had the desire, the resources, and the staff needed to begin such a project. Driven by a deep love for her husband and astronomy, Mrs. Draper agreed to support and fund Pickering’s endeavor.

Central to the project was a group of women known as “computers.” These women spent their days poring over photographic plates of the night sky to determine a star’s brightness, or spectrum type, and to calculate the star’s position. Sobel found in her research that Harvard was the only observatory that predominantly employed women for such positions. Some of these women, like Antonia Murray niece to Henry and Anna Draper, came to the observatory through family ties, while others were intelligent women looking for paid, engaging work. Many of these women entered the Observatory as young women and dedicated the rest of their lives to astronomical work. Pickering thought women to be just as capable as men in astronomical observation, and he believed their employment would further justify the need for women’s higher education. When the project began in 1883, Pickering employed six women computers, and in only a few short years, as the project expanded and funding increased, the number grew to 14.

Sobel knew when she started research for The Glass Universe that it was going to be all about the women. But approaching her subject matter and the book’s structure still proved a challenge. “It seemed daunting because there were so many women,” Sobel said in an interview with Smithsonian.com. Even after deciding to write the book, she says, “I wasn’t sure at the beginning how to manage them—whether it would be possible to treat them as a group or pick one and focus on the one and treat the others in a subsidiary way.” Knowing that it would not be easy, Sobel says, “I finally convinced myself it had to be the group, and the plates themselves would tie everybody together.”

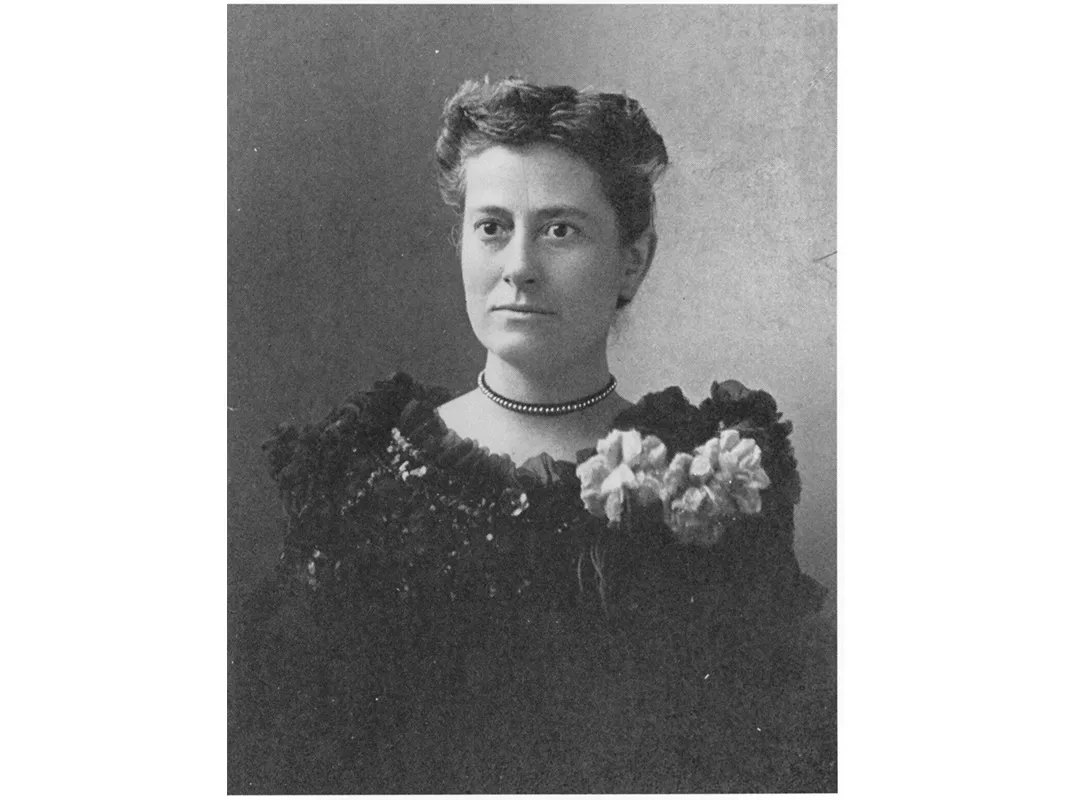

Of these women, Sobel singles out a select few who shone particularly brightly. Antonia Maury, for instance, developed an early version of the spectral classification system that distinguishes between giant and dwarf stars, and became the first woman to author part of the Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College, the Observatory’s annual publication of the year’s stellar classifications. Another “computer,” Williamina Fleming, discovered more than 300 variable stars and several novae and, along with Pickering updated, the classification system to account for variations in a star’s temperature.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt was the first to find a relationship between the variation in magnitude of a star’s brightness and the star’s period of variation, the fundamental relationship for measuring distance through space. Annie Jump Cannon—in addition to classifying thousands of star’s spectra—created a unified classification system from Maury’s and Fleming’s systems that more clearly defined the relationships among stellar categories, a system which is still in use today. Cecilia Payne was the first woman to receive a Ph.D. in astronomy at Harvard, and was the first to theorize about the abundance of hydrogen in the composition of stars.

All their discoveries, individually and together, came from hundreds of hours studying the hundreds of thousands of stars captured on the delicate glass plates.

Sobel expertly weaves together the scientific endeavor of mapping the universe with the personal lives of those closest to the century-long project. As in her earlier book Galileo’s Daughter, in which Sobel offers a nuanced look at Galileo’s battle with the church based on the letters of Galileo’s illegitimate daughter Maria Celeste, Sobel relies on correspondence and diaries to give readers a glimpse into the rich inner lives of her main characters. “I wanted to be able to say things that would distinguish the women one from another,” she says “If you just talk about their work, then they are cardboard figures.” By drawing on records of their lived experience, she makes them come alive.

Not only does Sobel show us what daily life was like for these women, but she also reveals how they felt about the work they did—and each other. In her diary, Fleming expressed both her love for Edward Pickering and her dissatisfaction with the low pay she received for her high-quality work. Cannon once wrote about the pride she felt in being the only woman and authority in a room of men, and her excitement at casting her vote for the first time after the passing of the 19th Amendment. We can delight in the way these women celebrated each other, and then be moved to tears by the loving manner in which they mourned each other upon their deaths.

For Sobel these personal details are integral to the story as a whole. “It’s not a story without them,” she says, “The characters have to make themselves present.”

It wasn’t just the women computers who sustained the project. Pickering also relied heavily on the work of amateur astronomers. During the 19th century, there was a trend among American and British scientists to try to cultivate a specific image for themselves as professionals. Part of that involved establishing science as a masculine pursuit and also delineating themselves from amateurs. But Pickering had great insight into what amateurs and women could accomplish. Sobel explains Pickering’s inclusiveness: “I think because he had been an amateur astronomer himself, he understood the level of dedication that was possible and the level of expertise.”

Amateurs may rank lower on the professional hierarchy of science, but as Sobel says, “These were people who came to the subject out of pure love and never stinted on time devoted to what they were doing, whether it was building a telescope or making observations or interpreting the observations.” The word “amateur,” after all, derives from the French “lover of.”

Though Fleming, Cannon, and others shouldered the hands-on work of observation, classification and discovery, the dedicated funding and enduring interest of women donors sustained the expanding work of the Observatory. The money that Mrs. Draper gave the observatory was equal to their entire annual budget. “That changed the fortunes of the observatory so dramatically,” says Sobel. “It increased the reputation of the observatory in the eyes of the world.”

In 1889, six years after Mrs. Draper made her generous donation, Catherine Wolfe Bruce gave another $50,000 toward the construction of the of the 24-inch astrophotographic telescope called “The Bruce,” which was installed in Arequipa, Peru. For Sobel, “Mrs. Bruce represents the appeal that astronomy has for people. You will meet people all the time who just tell you how they love astronomy ...and she was one of those,” she says. Bruce was integral to expanding the project into the Southern Hemisphere, and as Sobel says, her donation of the telescope named in her honor “made the Henry Draper Memorial super powerful.”

The Glass Universe tells a story of science that is not of individual, isolated genius, but rather an endeavor of collaboration and cooperation, setbacks and celebration. This book also tells a different story about women in science, one which has a long history. “I think people are surprised to learn that women were doing this kind of work at that time,” says Sobel. “It wasn’t developed in a recent administration. It’s just always been there.” Many people might know of the Harvard computers, but few understand the complexity of the work they did or even recognize their work as intellectual and scientific.

“This is something that is so ingrained in women: ‘Well, if a woman was doing it, it probably wasn’t that important,’” Sobel says. In her book, she shows us something else entirely: a story of scientific discovery with women at its fiery center.