The Great Feather Heist

The curious case of a young American’s brazen raid on a British museum’s priceless collection

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/9e/d49e653b-7d23-4116-8022-b73497aa7808/apr2018_a08_prologue.jpg)

Of all the eccentrics cataloged by “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” the most sublimely obsessive may have been Herbert Mental. In a memorable TV sketch, the character zigzags through a scrubby field, furtively tracking something. Presently, he gets down on all fours and, with great stealth, crawls to a small rise on which a birder is prone, binoculars trained. Sneaking up behind him, Mental stretches out a hand, peels back the flap of the man’s knapsack and rummages within. He pulls out a white paper bag, examines the contents and discards it. He pulls out another bag and discards it, too. He reaches in a third time and carefully withdraws two hard-boiled eggs, which he keeps.

As it turns out, Mental collects eggs. Not bird eggs, exactly. Birdwatchers’ eggs.

The British generally adore and honor eccentrics, the barmier the better. “Anorak” is the colloquialism they use to describe someone with an avid interest in something most people would find either dull (subway timetables) or abstruse (condensed matter physics). The term derives from the hooded raincoats favored by trainspotters, those solitary hobbyists who hang around railway platforms jotting down the serial numbers of passing engines.

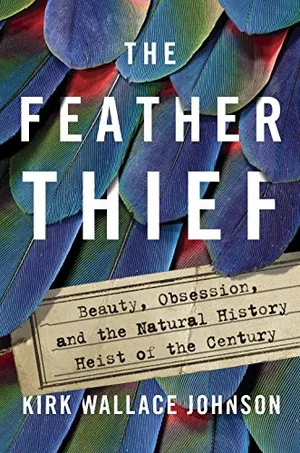

Kirk Wallace Johnson’s new book The Feather Thief is a veritable Mental ward of anoraks—explorers, naturalists, gumshoes, dentists, musicians and salmon fly-tyers. Indeed, about two-thirds of the way through The Feather Thief, Johnson turns anorak himself, chasing down stolen 19th-century plumes as relentlessly as Herbert Mental stalked the eggs of birders. Johnson’s chronicle of an unlikely crime by an unlikely crook is a literary police sketch—part natural history yarn, part detective story, part the stuff of tragedy of a specifically English kind.

The anorak who set this mystery in motion was Alfred Russel Wallace, the great English biologist, whose many eccentricities Johnson politely sidesteps. What piqued my curiosity and prompted a recent trip to London was that Wallace, a magnificent Victorian obsessive, embraced spiritualism and opposed vaccinations, colonialism, exotic feathers in women’s hats, and unlike most of his contemporaries, saw native peoples without the gaze of racial superiority. An evolutionary theorist, he was first upstaged, then totally overshadowed, by his more ambitious colleague Charles Darwin.

Beginning in 1854, Wallace spent eight years in the Malay Archipelago (now Malaysia and Indonesia), observing wildlife and paddling up rivers in pursuit of the most sought-after creature of the day: the bird of paradise. Decked out in strange quills and gaudy plumage, the male has developed spectacular displays and elaborate courtship dances whereby he morphs into a twitching, lurching geometric abstraction. Inspired by bird of paradise sightings—and reputedly while in a malarial fever—Wallace formulated his theory of natural selection.

By the time he left Malay, he had depleted the ecosystem of more than 125,000 specimens, mainly beetles, butterflies and birds—including five species from the bird of paradise family. Much of what Wallace had accumulated was sold to museums and private collectors. His field notebooks and thousands of preserved skins are still part of a continuous voyage of discovery. Today the vast majority of Wallace’s birds repose at a branch of the Natural History Museum, London, located 30 miles northwest of the city, in Tring.

The facility also houses the largest zoological collection amassed by one person: Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild (1868-1937), a banking scion said to have almost exhausted his share of the family fortune in an attempt to collect anything that had ever lived. Johnson pointed me to a biography of Rothschild by his niece, Miriam—herself a world authority on fleas. Through her account, I learn that Uncle Walter employed more than 400 professional hunters in the field. Wild animals—kangaroos, dingoes, cassowaries, giant tortoises—roamed on the grounds of the ancestral pile. Convinced that zebras could be tamed like horses, Walter trained several pairs and even rode to Buckingham Palace in a zebra-drawn carriage.

At the museum in Tring, Lord Rothschild’s menagerie was stuffed, mounted and encased in floor-to-ceiling displays in the gallery, along with bears, crocodiles and—somewhat disconcertingly—domestic dogs. The collections house nearly 750,000 birds, representing about 95 percent of all known species. Skins not on show are socked away in metal cabinets—labeled with scientific species names organized in taxonomic order—in storerooms off-limits to the public.

The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century

Home to one of the largest ornithological collections in the world, the Tring museum was full of rare bird specimens whose gorgeous feathers were worth staggering amounts of money to the men who shared Edwin's obsession: the Victorian art of salmon fly-tying.

Which brings us back to Johnson’s book. During the summer of 2009, administrators discovered that one of those rooms had been broken into and 299 brightly colored tropical bird skins taken. Most were adult males; drab-looking juveniles and females had been left undisturbed. Among the missing skins were rare and precious quetzals and cotingas, from Central and South America; and bowerbirds, Indian crows and birds of paradise that Alfred Russel Wallace had shipped over from New Guinea.

In an appeal to the news media, Richard Lane, then director of science at the museum, declared that the skins were of immense historical importance. “These birds are extremely scarce,” he said. “They are scarce in collections and even more scarce in the wild. Our utmost priority is working with the police to return these specimens to the national collections so that they can be used by future generations of scientists.”

At the Hertfordshire Constabulary, otherwise known as the Tring Police Station, I was given the lowdown of what happened next. Fifteen months into the investigation, 22-year-old Edwin Rist, an American studying the flute at London’s Royal Academy of Music, was arrested at his apartment and charged with masterminding the heist. Surrounded by zip-lock bags jammed with thousands of iridescent feathers and cardboard boxes that held what remained of the skins, he confessed immediately. Months before the break-in, Rist had visited the museum under false pretenses. Posing as a photographer, he cased the vault. A few months later, he returned one night with a glass-cutter, latex gloves and a large suitcase, and broke into the museum through a window. Once inside, he rifled through cabinet drawers and packed his suitcase with skins. Then he escaped into the darkness.

In court, a Tring constable informed me, Rist admitted that he had harvested feathers off many of the stolen birds and snipped the identifying tags off others, rendering them scientifically useless. He’d sold the gorgeous plumes online to what Johnson calls the “feather underground,” a flock of zealous 21st-century fly-tyers who insist on using the authentic plumes called for in the original 19th-century recipes. While most of the feathers can be obtained legally, there’s an extensive black market for the tufts of species now protected or endangered. Some Victorian flies require more than $2,000 worth, all wound around a single barbed hook. Like Rist, a virtuoso tyer, a surprising percentage of fly-tyers have no idea how to fish and no intention of ever casting their prized lures to a salmon. An even greater irony: salmon can’t tell the difference between a spangled cotinga plume and a cat’s hairball.

In court, in 2011, Rist sometimes acted as if the feather theft was no big deal. “My lawyer said, ‘Let’s face it, the Tring is a dusty old dump,’” Rist told Johnson in the only interview he has granted about the crime. “He was exactly right.” Rist claimed that after about 100 years “all the scientific data that can be extracted from [the skins] has been extracted.”

Which is not remotely true. Robert Prys-Jones, the retired former head of the ornithology collection, confirmed to me that recent research into feathers from the museum’s 150-year-old seabird collection helped document rising heavy-metal pollutant levels in the oceans. Prys-Jones explained that the capacity of skins to provide both new and important information only increases over time. “Tragically, the specimens still missing as a result of the theft are vanishingly unlikely to be in a physical state, or attached to data, that would make them of continuing scientific utility. The futility of the use to which they have probably been put is deeply sad.”

Though Rist pleaded guilty to burglary and money laundering, he never served jail time. To the dismay of museum administrators and the Hertfordshire Constabulary, the feather thief received a suspended sentence—his lawyer argued that the young man’s Asperger’s syndrome was to blame and that the caper had merely been a James Bond fantasy gone wrong. So what became of the tens of thousands of dollars Rist pocketed from the illicit sales? The loot, he told the court, went toward a new flute.

A free man, Rist graduated from music school, moved to Germany, avoided the press and made heavy-metal flute videos. In one posted to YouTube under the nom de plume Edwin Reinhard, he performs Metallica’s thrash-metal opus Master of Puppets. (Sample lyric: “Master of puppets, I’m pulling your strings / Twisting your mind and smashing your dreams.”)

**********

Not long ago I caught up with Johnson, the author, in Los Angeles, where he lives, and together we went to the Moore Lab of Zoology at Occidental College, home to 65,000 specimens, largely birds from Mexico and Latin America. The lab has developed protocols that allow for the extraction and processing of DNA from skins that date to the 1800s. The lab director, John McCormack, considers the specimens—most of which were gathered from 1933 to ’55—a “snapshot in time from before pristine habitats were destroyed for logging and agriculture.”

We entered a private research area lined with cabinets not unlike the ones at Tring. McCormack unlocked the doors and pulled out trays of cotingas and quetzals. “These skins hold answers to questions we have not yet thought to ask,” said McCormack. “Without such specimens, you lose the possibility of those insights.”

He opened a drawer that contained an imperial woodpecker, a treasure of the Sierra Madre of northwest Mexico. McCormack said timber consumption partly accounts for the decline of this flamboyant, two-foot-long woodpecker, the world’s largest. Logging companies viewed them as pests and poisoned the ancient trees they foraged in. Hunting reduced their numbers, too.

Told that he had shot and eaten one of the last remaining imperials, a Mexican truck driver reportedly said it was “un gran pedazo de carne” (“a great piece of meat”). He may have been the final diner. To paraphrase Monty Python’s Dead Parrot sketch: The imperial woodpecker is no more! It is an ex-species! Which might have made a splendid Python sketch if it weren’t so heartbreaking.

Editor’s note, April 3, 2018: A photo caption in this article originally identified objects as dating from the mid-1900s. They are from the mid-19th century. We regret the error.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.