Greenland’s Glaciers Are Hemorrhaging Ice, Best Seen By Photos from Space

Satellites snap pictures of Greenland’s glaciers, which a new study shows are vanishing at an accelerated pace, helping to spike global sea levels

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Surprising-Science-Greenland-631.jpg)

On the morning of July 16, 2010, a hunk of ice four times the size of Manhattan cracked away from the tongue of Greenland’s Petermann Glacier and drifted to sea as the largest iceberg since 1962. Just two years later, another massive section of ice calved from the same glacier. Icebergs like these don’t stay put in the Arctic–they get picked up by currents and ushered to warmer climates, melting along the way.

According to a new study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, Greenland’s melting glaciers and ice caps sent 50 gigatons of water gushing into the oceans from 2003 to 2008. This comprises about 10 percent of the water flowing from all ice caps and glaciers on Earth. The research comes on the heels of a study last year that showed the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica are disappearing three times faster than in the 1990s, and that Greenland’s is melting at an especially accelerated rate. In the new study, scientists were able to put an even finer point to the ice-melt situation by separating out the glaciers and ice caps from the ice sheet, which blankets 80 percent of the island. What they discovered is that Greenland’s glaciers are actually melting more quickly than the ice sheet.

Studies such as these demonstrate the impacts of a warming climate on Greenland’s glaciers. But, as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. Visual evidence of this liquefaction is captured by NASA satellites, which are able to take snapshots of calving glaciers and document longer-term ice melt. NASA displays photos of the glaciers in its State of Flux photo gallery, along with a rotating collection of satellite images that illustrate other changes to the environment, including wildfires, deforestation and urban development.

The photos, with their “now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t” quality, illustrate how glaciers are fast becoming ephemeral. Here are a few stark examples:

The set of images above shows the edge of Greenland’s Helheim Glacier, located on the fringe of the Greenland Ice Sheet, as captured by a satellite in 2001, 2003 and 2005. The calving front is marked by the curved line through the valley, while bare ground appears brown or tan and vegetation is red.

According to NASA, when warmer temperatures initially cause a glacier to melt, it can spark a chain reaction that accelerates the thinning of the ice. As the edge of the glacier begins to liquefy, it crumbles, creates icebergs and eventually disintegrates. The loss of mass throws the glacier off balance, and further thinning and calving occurs, a process that stretches the glacier through its valley. Total ice volume decreases then shrinks the glacier as calving carries ice away. Helheim’s calving front stayed put from the 1970s until 2001, at which point the glacier began hasty cycles of thin, advance, and dramatic retreat, ultimately moving 4.7 miles toward land by 2005.

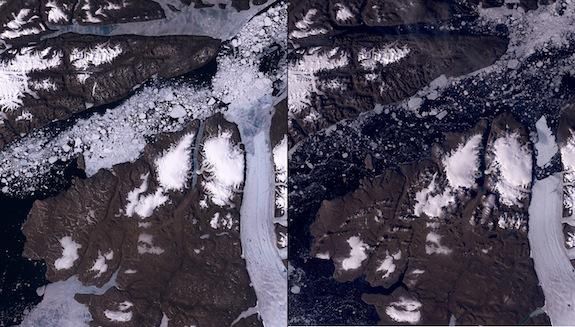

The massive calving event at Petermann Glacier in 2010 is pictured in these two images. The glacier is the white ribbon on the right side of each photo, and its tongue extends into the Nares Strait, which appears as a bluish-black stripe across the center of the right image and is heavily flecked with white chunks in the photo on the left. In the first image, the tongue of the glacier is intact; in the second, a huge chunk of ice has broken off and can be seen floating away through the fjord. This iceberg was 97 square miles in size–four times bigger than the island of Manhattan.

In the summer of 2012, a second massive iceberg crumbled away from the Petermann Glacier. In these images, the glacier is the white ribbon snaking up from the bottom right. If you follow the tongue up, you’ll see that it appears intact in the photos at left and center (though the center image has an ominous crack spanning its width), which were taken the day before the calving occurred. The photo on the right shows that it crumbled as the glacier calved.

Given that Greenland experienced an exceptionally warm summer in 2012 and temperatures were higher than average this winter, 2013 is primed for more melting and massive icebergs. Last year’s ice-melt season lasted two months longer than the average since 1979, and this year’s is already off to an inauspicious start. It kicked off on March 13 with the sixth-smallest sea-ice area on record for Greenland, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. What will the new summer calving season bring?