The History and Science Behind Your Terrible Breath

Persistent mouth-stink has been dousing the flames of passion for millennia. Why haven’t we come up with a cure?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/5d/925d4deb-c921-4054-bd28-54a0b17d0515/the_death_of_cleopatra_arthur.jpg)

In The Art of Love, the Roman poet Ovid offers some words of advice to the amorous. To attract the opposite sex, he writes, a seductive woman must learn to dance, hide her bodily blemishes and refrain from laughing if she has a black tooth. But above all, she must not smell foul.

“She whose breath is tainted should never speak before eating,” Ovid instructs, “and she should always stand at a distance from her lover's face.”

Though the quality of this advice is questionable, the dilemma it describes remains all too familiar. Ancient peoples around the world spent centuries experimenting with so-called cures for bad breath; scientists today continue to puzzle over the factors that lay behind it. Yet stinky breath continues to mystify us, haunting our most intimate moments and following us around like a green stench cloud.

Why is this scourge so persistent? The answer requires a 2,000-year detour through history, and might say more about our own social neuroses than about the scientific causes of this condition.

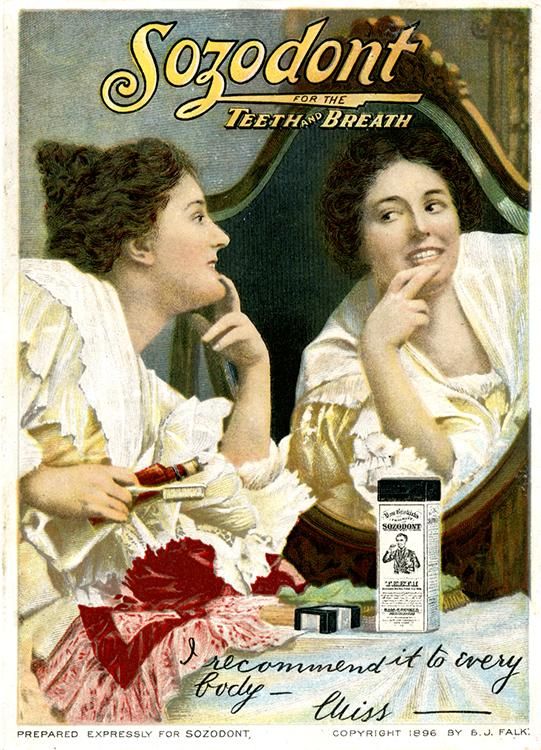

Our efforts to battle bad breath showcase a history of human inventiveness. The ancient Egyptians, for instance, appear to have invented the breath mint some 3,000 years ago. They created concoctions of boiled herbs and spices—frankincense, myrrh and cinnamon were popular flavorings—mixed with honey to make sweets that could be chewed or sucked. In the 15th century, the Chinese invented the first bristle toothbrushes, made by harvesting hairs from pigs' necks. More than 5,000 years ago, Babylonians began trying to brush away bad breath with twigs.

Talmudic scholars report that the Torah decried bad breath as a “major disability,” meaning it could be grounds for a wife to seek divorce or could prevent priests from carrying out their duties. Fortunately, the Talmud also suggests some remedies, including rinsing with a mouthwash of oil and water, or the chewing of a mastic gum made from tree resin. This resin, which has since been shown to have antibacterial properties, is still used as gum in Greece and Turkey today.

In Pliny the Elder’s early encyclopedia Natural History, penned a few years before he was killed in the Vesuvius eruption, the Roman philosopher offered this advice: “To impart sweetness to the breath, it is recommended to rub the teeth with ashes of burnt mouse-dung and honey." Pliny added that picking one's teeth with a porcupine quill was recommended, while a vulture's feather actually soured the breath. While many of these efforts no doubt freshened the breath temporarily, it seems that none provided a lasting fix.

Literary references from around the world confirm that bad breath has long been regarded as the enemy of romance. In the poet Firdawsi's 10th-century Persian epic, the Shahnama, persistent mouth-stink dramatically changes the course of history. The tale tells of how King Darab's young bride Nahid was sent home to Macedonia because of her intolerable bad breath. Unbeknown to her either her husband or father, King Phillip, she was already pregnant with a baby boy.

Her son would grow up to be none other than Iskander—better known as Alexander the Great. That meant that, in Firdawsi's tale, Alexander was not a foreigner but a legitimate king of Persian blood reclaiming his throne.

In Geoffrey Chaucer's classic Canterbury Tales, the “jolly lover” Absalon prepares for a kiss by scenting his breath with cardamom and licorice. (Unfortunately, the object of his attentions ends up presenting him with her naked rear-end rather than her lips.) In describing the horrors of Rome, William Shakespeare's Cleopatra laments that “in their thick breaths, / Rank of gross diet, shall we be enclouded, / And forced to drink their vapour.” In Mucho Ado About Nothing, Benedick muses, “If her breath were as terrible as her terminations, there were no living near her; she would infect to the north star.”

Jane Austen's elegant novels don't dwell on topics like bad breath. But the author was more candid in her personal correspondence. In a letter to her sister Cassandra, she once complained of some neighbors: “I was as civil to them as their bad breath would allow me.”

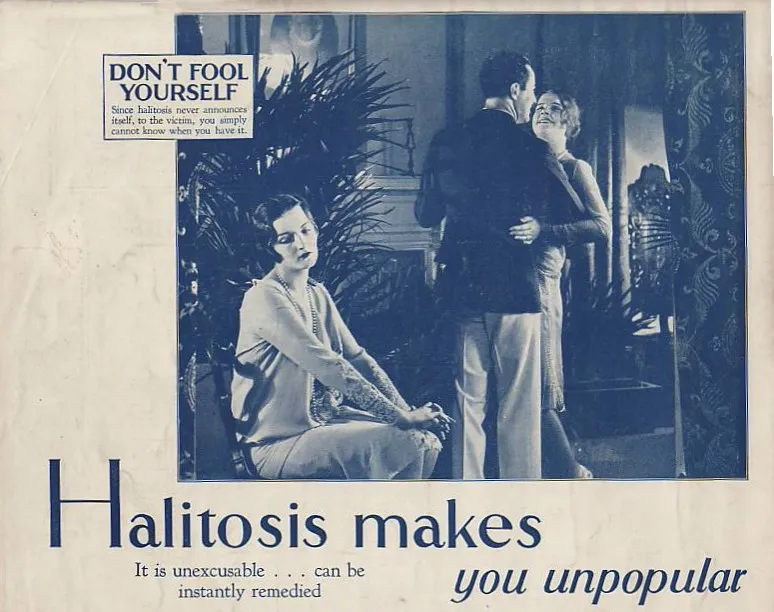

While historic peoples were certainly aware of this mood-killing scourge and sought ways to counteract it, it wasn’t until the early-20th century that the affliction officially became a medical diagnosis. That’s when the condition known as halitosis came into being, thanks in large part to the savvy marketing efforts of a company called Listerine.

In the 1880s, Listerine wasn’t just a mouthwash. It was a catch-all antiseptic, sold as anything from a surgical disinfectant to a deodorant to a floor cleaner. Historic advertisements show that Listerine was pitched as a supposed remedy for diseases from dysentery to gonorrhea. Others assured consumers that all they had to do was “simply douse Listerine, full strength, on the hair” to get rid of off-putting dandruff.

What the brand needed was a focus. So in 1923, Listerine heir Gerard Barnes Lambert and his younger brother Marion were brainstorming which of Listerine's many uses might become its primary selling point. Gerard later recalled in his autobiography asking the company chemist about bad breath. “He excused himself for a moment and came back with a big book of newspaper clippings. He sat in a chair and I stood looking over his shoulder. He thumbed through the immense book,” he writes.

“Here it is, Gerard. It says in this clipping from the British Lancet that in cases of halitosis . . .” I interrupted, “What is halitosis?” “Oh,” he said, “that is the medical term for bad breath.”

[The chemist] never knew what had hit him. I bustled the poor old fellow out of the room. “There,” I said,” is something to hang our hat on.”

Seizing on the idea, the elder Lambert began leveraging the term as a widespread and truly disgusting medical condition, one that destroyed exploits in love, business and general social acceptance. Fortunately, this national scourge had an easy and effective cure: Listerine. Today, his product has become known as an effective weapon against the germs that cause bad breath.

The halitosis campaign capitalized on several wider trends of the time. One was a growing awareness—and fear—of germs and how they spread in the early 20th century. “There was a rising consciousness” of germs, notes Juliann Sivulka, a historian who studies 20th-century American advertising at Waseda Univesity in Tokyo, Japan. “A lot of products were introduced as promoting health with regards to germs, things like disposable paper cups and Kleenex tissues.”

In addition, the general social liberation of the era made all kinds of previously unmentionable subjects suddenly fit for the public eye. “There were things discussed in advertising that were never mentioned before—things relating to bodily functions which, in the Victorian era, were taboo,” says Sivulka. “A glimpse of the stocking was something shocking; you'd never refer to things like athlete's foot, or acne.” Now advertisers boldly referred to these scourges and their potential cures, using the attention-grabbing strategies of tabloid journalism.

Beginning in the 1930s, Listerine ran ads featuring bridesmaids whose breath doomed them to spinsterhood; men who seemingly had everything, yet were social pariahs; and mothers whose odors ostracized them from their own children. In the 1950s, Listerine even produced comic books to illustrate how the product improved the lives of football stars and cheerleaders. The campaign was so successful that Lambert—who had many accomplishments in fields ranging from businesses to the arts—lamented that his tombstone would bear the inscription: “Here lies the body of the Father of Halitosis.”

Why did the halitosis-fueled Listerine campaign seem to strike such a chord? Lambert’s campaign exploited a primal need for social acceptance and fear of rejection—fears that remain alive and well in those who suffer from bad breath, says F. Michael Eggert , founder of the University of Alberta's Bad Breath Research Clinic. “We're social animals, and very conscious of the signals that other people give off,” says Eggert, who hears from many of his patients about the reactions of those around the breather.

“People are fearful about social interactions,” he adds. “If somebody recoils from them for some reason, maybe at work, they begin believe that it's bad breath that's coming from them.”

What actually causes these most offensive of oral odors? It’s only in recent times that scientists have begun to make some headway on this mouthborne mystery. What they’re finding is that, while notorious foods like sardines, onions and coffee can surely inflect our aromas, what we eat isn't ultimately to blame. Instead, the real culprits are invisible, microscopic bacteria that hang out around your tongue and gums, feasting on tiny bits of food, postnasal drip and even oral tissues.

Identifying these bacteria is the first step toward figuring out how to manage them, says Wenyuan Shi, chair of oral biology at the University of California at Los Angeles School of Dentistry. According to Shi, most bad breath is produced by the types of bacteria that give off particularly smelly gasses, especially sulfates, to which most people seem especially averse. (For reference, the smell of sulfates reminds most of rotten eggs.)

Saliva is the body's natural way of rinsing these bacteria and their offending olfactory byproducts out of the mouth. That means that a dry mouth is a smelly mouth: Excessive talking or lecturing, mouth breathing, smoking or even some medicines can help kickstart bad breath, says Shi. But merely keeping your mouth moist won’t guarantee a fresh exhalation.

Unfortunately, all the weapons we use against these bacterial beasties—brushes, floss, mouthwash—can only mask their impact or temporarily keep them at bay. In other words, we may be doomed to the Sisyphean task of getting rid of these bacteria day after day, only to have them come back in the morning full force. As Shi puts it: “It’s a constant battle.”

“The problem with hygiene is that it's just a short-term solution that's never really going to generate a long-term effect,” he explains. “No matter how much you clean your mouth, by the time you wake up you have as many if not more bacteria in your mouth as before. … Using mouthwash, brushing, or scraping your tongue are a lot better than nothing but at most they just get rid of the surface layer and the bacteria are easily growing back.”

It's worth noting that not all bad breath is caused by bacteria. Some stenches have nothing to do with the mouth, but actually originate in the stomach; in rare cases, bad breathe can even suggest serious metabolic problems like liver disease, Eggert notes. "It's not purely dental and it's not purely oral,” he says. “There's a very significant component of individuals who have bad breath that has nothing to do with their mouth at all.”

But when it comes to victory over bacteria-based bad breath, at least, Shi harbors hope. His vision doesn't include wiping out all the bacteria in our mouth, because many of them are valuable contributors to our oral ecosystems.

“The road map to an ultimate solution is clearly going to be more of an engineered community,” he says. “That means seeding more of the bacteria that don't generate odors, and targeting treatment to get rid of the ones that are causing the problem. It's like weeds growing in your grass: If you use a general herbicide, you damage your healthy lawn, and it's always the weeds that come back first. The solution is to create a healthy lawn and have all the different niches occupied so you don't give those weeds a chance to grow back.”

Until that sweet-smelling day, try to keep some perspective. While socially repugnant, in most cases, occasional mouth-stink is generally harmless. So if you’re afflicted with less-than-rosy breath every now and then, remember: You’re not alone. Love isn't always eternal, but bad breath just might be.