The Hidden Biases That Shape Natural History Museums

Here’s why museum visitors rarely see lady animals, penis bones or cats floating in formaldehyde

:focal(1475x902:1476x903)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/ff/45ff2eeb-f5c5-49a9-8664-9b9f10a263bd/nhmuseum.jpg)

Natural history museums are magical places. They inspire awe and wonder in the natural world and help us understand our place within the animal kingdom. Behind the scenes, many of them are also undertaking world-changing science with their collections. Each year dozens of new species are discovered hiding within their collections, from extinct river dolphins to new dinosaurs to sacred crocodiles.

At the same time, the parts of museums that are open to the public are spaces made for people, by people. We might like to consider them logical places, centered on facts, but they can’t tell all the facts—there isn’t room. Similarly, they can’t show all the animals. And there are reasons behind what goes on display and what gets left in the storeroom.

The biases that can be detected in how people talk about animals, particularly in museums is one of the key themes of my new book, Animal Kingdom: A Natural History in 100 Objects. Museums are a product of their own history, and that of the societies they are embedded in. They are not apolitical, and they are not entirely scientific. As such, they don’t really represent reality.

1. Where are all the small animals?

Museums are overwhelmingly biased towards big beasts. It’s not difficult to see why; who can fail to be awed by the sight of a 25 meter-long blue whale? Dinosaurs, elephants, tigers and walruses are spectacular. They ooze presence. It is easy for museums to instill a sense of wonder with animals like this. They are the definition of impressive.

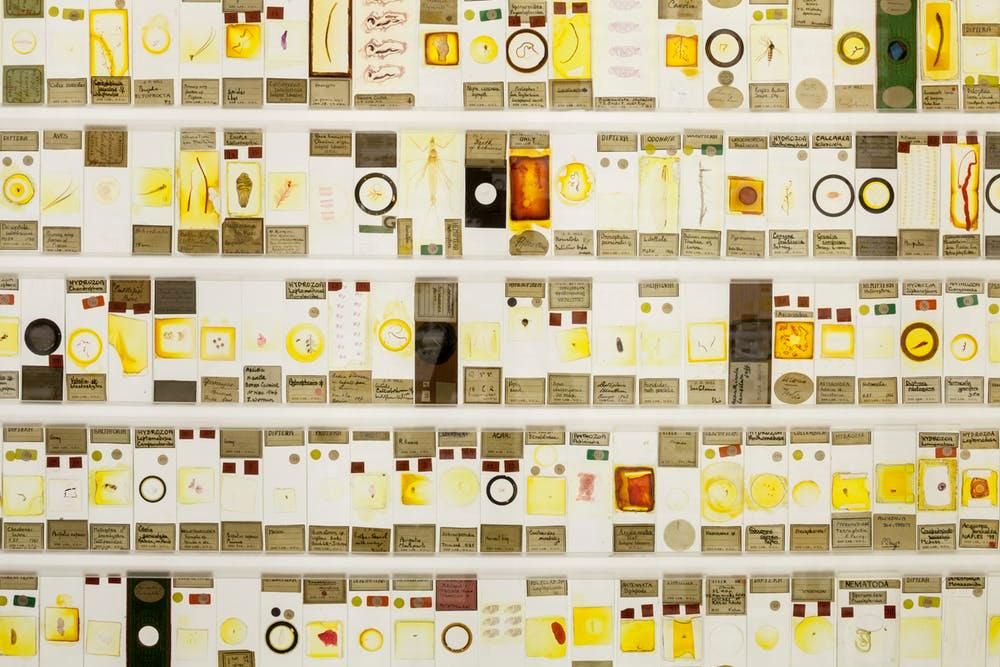

And so these are the kind of specimens that fill museum galleries. But they only represent a tiny sliver of global diversity. Invertebrate species (animals without backbones) outnumber vertebrates by more than 20 to one in the real world, but in museums they’re far less likely to be displayed.

2. Where are all the females?

If we think about the sex ratio of animal specimens in museum galleries, the males are thoroughly over-represented. Curator of Natural Science at Leeds Museum Discovery Centre, Rebecca Machin, published a case study in 2008 of a typical natural history gallery and found that only 29 percent of the mammals, and 34 percent of the birds were female. To some extent this can be explained by the fact that hunters and collectors were more inclined to acquire—and been seen to overcome—animals with big horns, antlers, tusks or showy plumage, which typically is the male of the species. But can this display bias be excused? It is a misrepresentation of nature.

Machin also found that if male and female specimens of the same species were displayed together, the males were typically positioned in a domineering pose over the female, or just simply higher than her on the shelf. This was irrespective of biological realities.

Looking at the ways in which the specimens had been interpreted—even in labels that have been written very recently—she found that the role of the female animal was typically described as a mother, while the male came across as the hunter or at least had a broader role unrelated to parenting. We have to wonder what messages this might give museum visitors about the role of the female.

3. Where is all the gross stuff?

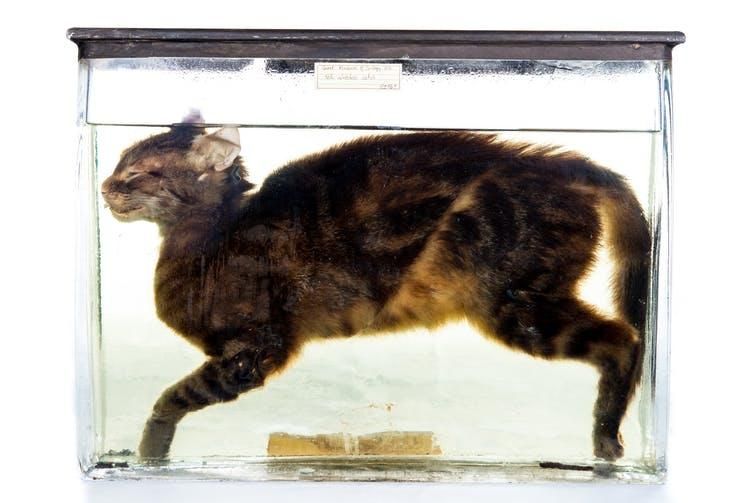

When it comes to animal groups that people consider cute (i.e. mammals), why is it that specimens preserved in jars are displayed less regularly than taxidermy? I suspect that one reason is that fluid preservation, unlike taxidermy, cannot hide the fact that the animal is obviously dead. It is likely that museums shy away from displaying mammals in jars—which are very common in their storerooms—because visitors find them more disturbing and cruel than the alternatives.

I have encountered few objects that cause visitors to have such a strong negative response than the bisected cat below, displayed in the Grant Museum of Zoology at UCL, and this is interesting too. They seem more concerned about this cat than when they are confronted with the preserved remains of endangered, exotic creatures. The human connection with this species is so strong that many people find it challenging to see them preserved in a museum.

There are other reasons to think that museum curators modify their displays to cater to the sensibilities of their visitors.

The majority of mammal species, for example, have a bone in their penis. Despite the prevalence of skeletons of these animals in museum displays, it is extraordinarily rare to see one with its penis bone attached. One reason for this is the presumed prudishness of the curators, who would remove the penis bone before putting them on display (another is that they are easy to lose when de-fleshing a skeleton).

4. Colonial skews

There is real unevenness in which parts of the world the animals in our museums come from. The logistics of visiting exotic locations means that some places were easier to arrange transport to than others, and there may also have been some political motivation to increase knowledge of a particular region.

Knowledge of a country’s natural history equates to knowledge of the potential resources—be they animal, vegetable or mineral—that could be exploited there. Collecting became part of the act of colonization; staking a claim of possession. For these reasons, collections are often extremely biased by diplomatic relationships between nations. In the UK, it is easy to observe the bias of the former British Empire in what we have in our museums, and that is true of any country with a similar history. Collections of Australian species in British museums dwarf what we hold from China, for example.

Museums are rightly celebrated as places of wonder and curiosity, and also science and learning. But if we look closely at their public-facing displays, we can see that there are human biases in the way nature is represented. The vast majority of these are harmless foibles—but not all.

My hope is that when people visit museums they may be able to consider the human stories behind the displays they see. They might consider the question of why is all that stuff there: what is that museum—or that specimen—doing? What is it for? Why has someone decided it deserves to take up the finite space in the cabinet? The answers could be reveal more about the creators of natural history museums than about natural history itself.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Jack Ashby, Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology, UCL