What Elephants, Zebras and Lions Do When They Think No One’s Watching

The stunning results when a photographer uses remote cameras to capture Africa’s great beasts

Elephants are best photographed on overcast days. Their gray hides tend to look smudgy black against sapphire African skies, but they glow against charcoals and whites, Anup Shah explains. Besides, elephants and clouds travel in the same lazy, majestic manner: they drift.

Like most veteran wildlife photographers working in the Serengeti and Masai Mara ecosystems, Shah has spent his career “at a respectful distance” from his subjects, clicking away with a foot-long telephoto lens from an off-road vehicle’s rolled-down window. For his safety and the animals’, stepping out of the truck isn’t an option—and neither is getting close.

Some animals flee at the first distant rumble of his engine—especially warthogs, whose posteriors are perhaps their most frequently immortalized part. But even with lions and other large creatures that don’t startle as easily, “there is no intimacy or immediacy,” Shah says. “There is a barrier—your car and that huge photographic space between you and the animals.”

Reading about hidden cameras in a photography magazine a few years ago, Shah resolved to conceal remote-control contraptions around the grasslands, so that the animals would wander into his sights while still at ease. As he positions his cameras in the vastness of the savanna, he relies on an old-school understanding of animal behavior: identifying ambush spots and wallows, finding the exact trees where cheetahs prefer to pee, learning the habits of baby giraffes and calculating the daily movements of clouds and elephants.

Shah usually parks his truck about 50 to 100 yards away from the scene he plans to photograph. Each hidden camera has a built-in video link, connecting it to a portable DVD player. After disguising the camera with dirt and dung, he returns to his vehicle and studies the screen, ready to snap close-ups by tripping the shutter with a button.

His goal is to take himself out of the scene as much as possible, and get the viewer even closer to the animals. “When I look at pictures that excite me,” Shah says, “it is intimate photography from the streets of New York City, where the photographer has been within a yard or two of the subject, and that gives you the feeling that you are there in the middle of the street talking to this stranger. I wanted to bring people right to the streets of the Serengeti.”

Shah’s hidden camera photos reveal unseen details of familiar animals: mazes of elephant wrinkles, the shaggy geometry of a zebra’s belly, a warthog’s ecstatic expression as a family of hungry mongooses harvests ticks from its thick skin. While telephoto lenses often look down on a subject, Shah’s cameras gaze up from the ground where they’re hidden. Dirt is an important narrative tool: a long curve of dust describes a migration, juicy mud holes suggest the private pleasures of elephants. Despite the horrific smell, Shah often targets animals feeding on carcasses. Zebra ribs rise like steel beams, new construction in a streetscape of grass.

Often the scene that unfolds is not exactly what he’d envisioned. Herds dillydally; baboons photobomb; crocodiles linger. Half a dozen of his hidden cameras have met less-than picturesque ends, stolen by cunning animals or crushed under their hooves. Secreting a camera on a riverbank one morning, in anticipation of a wildebeest crossing, “I waited and waited and waited,” Shah recalls, “and to my horror, the river water rose and rose and rose.” As the herd debated whether to cross, Shah debated whether to rescue his camera: “Should I save an expensive object and risk scaring the animals?” The camera drowned.

In addition to lots of no-shows, Shah struggles with subjects that materialize more suddenly than expected. Shortly after he placed his camera near one pond, a 4,000-pound hippo popped up from the water with the buoyancy of a bath toy, its pink ears pert and alert. “I had to beat a hasty retreat,” Shah says, “But that is probably the best hippo picture I’ll ever get.”

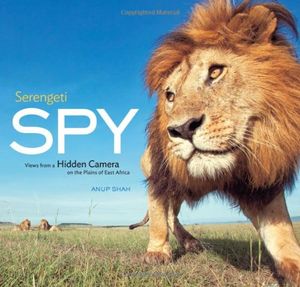

Serengeti Spy: Views from a Hidden Camera on the Plains of East Africa