History of the Hysterical Man

Doctors once thought that only women suffered from hysteria, but a medical historian says that men were always just as susceptible

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hysterical-Men-Mark-Micale-631.jpg)

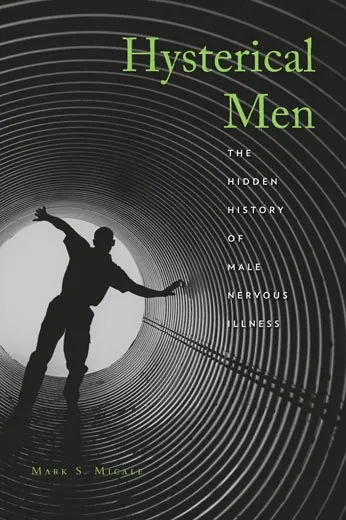

The term “hysteria” comes from the Greek word for “womb” and refers to a disease that was once diagnosed almost exclusively in women. Women’s asthma, widow’s melancholy, uterine epilepsy -- these were all synonyms for a strange complex of symptoms that included unexplained pains, mysterious convulsions, sudden loss of sensation in the limbs and dozens of other complaints without apparent physical cause. Particularly during the Victorian age, doctors thought hysteria demonstrated the general fragility of the fair sex. The best remedy was a good marriage. But all the while untold numbers of men were suffering from the same illness. In his new book, Hysterical Men: The Hidden History of Male Nervous Illness, Mark Micale, a professor of the history of medicine at the University of Illinois, explores the medical tradition of ignoring masculine “hysteria,” and its cultural consequences.

What is hysteria?

It’s more or less impossible to define hysteria in a way that a physician today would find acceptable. The meaning has changed dramatically over time. It’s an enormous collection of possible symptoms that are of the body but that can’t be traced to any known physical disease. It can look like a manifestation of epilepsy, a brain tumor, advanced syphilis, Parkinson’s, but upon examination it’s none of these. Ultimately the suspicion forms that though these are bodily manifestations, the cause is psychological.

Why don’t we hear that diagnosis anymore?

The term is no longer used because American psychiatrists over the past half century have decided not to use it. They’ve renamed it, breaking it into various parts, labeling it differently. These successor categories all have the quality of sounding more scientific, which is no coincidence. There’s “somatization disorder” and “psychogenic pain disorder” and a whole string of other labels that basically cover the same category that Freud and his predecessors were comfortable calling hysteria.

Why was it so rarely diagnosed in men?

It’s not that the behavior didn’t exist. It did exist. It was rampant. Men were as prone to nervous breakdown as women were. It was not diagnosed for social and political reasons. Men were believed to be more sane, more motivated by reason, more in control of themselves emotionally. If you were to diagnose honestly, that would have pretty quickly called into the question the difference between the sexes and the idea that men were more self-possessed than their fragile, dependent female counterparts. Ultimately it comes down to patriarchy and power.

For a brief time, in Georgian England, it was almost fashionable to be a hysterical man. Why?

In 18th-century England and Scotland, it was acceptable to acknowledge these symptoms in men and call them “nervous.” The label was applied, and self-applied, to men who were upper-middle or upper class, or aspired to be. They interpreted these symptoms not as a sign of weakness or unmanliness but as a sign that they had a refined, civilized, superior sensibility. If the weather depresses you, if you get emotionally involved in reading a Shakespeare play, if you tire out easily, it’s not because you’re unmanly, it’s because you have a particularly sophisticated nervous system that your working-class counterparts do not. And if you can convince other people in society of this, then doesn’t it mean you’re better suited to govern the state wisely?

How did historical events, like Napoleon’s conquests, shape hysterical diagnoses?

The history of masculinity is very caught up with contemporary events. If there’s something in the history of the time that requires men to suddenly fulfill their most traditional, stereotypical roles -- such as defending the homeland -- then that tends to be a period of very conservative gender attitudes. That ‘s what happened with the Napoleonic period. When there’s a war, and one country after another is being invaded by this short, upstart Frenchman, what becomes important is producing virile soldiers. During and after the Napoleonic period, and especially in Britain, there was a change in how nervous disorders in men were seen. They went from being signs of refinement and civilization to signs of weak and unmanly behavior -- and, a generation later, as signs of physical and biological degeneration.

What about the fact that doctors of the day were almost all male?

Doctors themselves are products of a society and, in the case of Europe when the medical profession first rises, every doctor is by law male, because women are barred from university. Ninety percent of the doctors are coming from the rising middle classes and they were very concerned, as part of their professional ascent, that they appear as men of science. They saw middle-class men as especially rational and controlled and self-disciplined. It’s not surprising that when they saw cases of hysteria in middle-class men behind closed doors, they just didn’t theorize about or print the cases in the way they do so extensively with their women cases. It’s their own image, in their own minds, that they’re protecting. Wild behaviors were an object of study, not something they saw in themselves.

Did writing this book involve assessing any hysterical tendencies of your own?

I joke with my colleagues that, despite the title, this book is not my autobiography. But it does help to be somewhat self-aware psychologically. For me it’s a fascination with a behavior pattern that is opposite my own. Obsession and over-control are my chosen pathologies, my neuroses of choice, and for that reason I’ve been interested in those who negotiate the world through hysterical outbursts.

How has post-traumatic stress disorder challenged and changed our understanding of hysteria?

There should be an entire successor volume beginning with World War I and shell shock and coming up to the present. What some people started calling “male hysteria” was relabeled “shell shock” early in the 20th century. The relabeling is interesting because the term is new, not associated with women, and still suggests an honorable cause, a physical trauma to the nerves. These cases almost exclusively involved men, engaged in an honorable male activity. Since about 1980 they’ve used the term post-traumatic stress disorder. It’s extremely easy to show continuity between the symptoms of late 19th-century male hysteria, World War I shell shock, and present-day PTSD. The sign that suggests that we’ve made progress is that less and less in cases of PTSD is seen as comprising a soldier’s general identity, as something unmasculine.

What men in the modern popular culture would have been described as hysterics? Tony Soprano comes to mind.

A stereotypical example is Woody Allen, but Tony Soprano is a good one. He is struggling with a different model of manhood, one that is gritty and violent, and ethnic and Italian. He breaks out into these unexplained rashes and anxiety fits. He wants the doctors to find an organic cause so he doesn’t have to be considered a “head case.”

He’s trying so hard officially to be hyper-masculine, to be an Italian, to have sex with strange women and so forth but he can’t handle his own neuroses.

How will new technology, the emotional outlets online, change our understanding of the male mind?

We live in this culture of total media that never shuts down. Anyone who is interested or thinks they are suffering can go online and inevitably find chat rooms, self-help literature, a lot of information. They self-diagnose, search out a therapist, or share illness stories. There’s a lot of medical self-fashioning going on today as a result of the electronic media, which helps us determine how we should think about ourselves, in health and in sickness. You might say women were more inclined to do this, but I don’t think so.