In the Everglades, everything still looks the same. The waving saw grass, the cypress and pine trees draped with air plants, the high, white clouds parked like dirigibles above their shadows—if you’ve been to the Everglades before, and you go back, you’ll still find these. But now there is also a weird quiet. In the campsites of Everglades National Park, raccoons don’t rattle the trash can lids at four in the morning. Marsh rabbits don’t scatter with a nervous rustle on the hiking trails as you walk by. Tires don’t shriek when somebody brakes to avoid an opossum transfixed by headlights in the middle of the road. In fact, roadkill, which used to be common in this wildest part of Florida, is no longer seen.

The raccoons and marsh rabbits and opossums and other small, warmblooded animals are gone, or almost gone, because Burmese pythons seem to have eaten them. The marsh’s weird outdoor quiet is the deep, endlessly patient, laser-focused quiet of these invasive predators. About two feet long when hatched, Burmese pythons can grow to 20 feet and 200 pounds; they are among the largest snakes in the world. The pythons are mostly ambush hunters, and constrictors. They kill smaller animals by biting them on or near the head and suffocating them as they are swallowed. Larger animals are seized wherever is convenient, and crushed and strangled in the coils before and during swallowing. Large constrictor snakes have not existed in North America for millions of years. Native wildlife species had never seen them before, and may not recognize them as predators.

In Miami, a center of the exotic pet trade, dealers used to import them from Southeast Asia by the tens of thousands. It is now illegal to import or purchase Burmese pythons in Florida. Probably, at some point, python owners who no longer wanted to care for them let them go in the Everglades.

By the mid-1990s, the pythons had established a breeding population. For 25 years they have been eating any animals they can get their mouths around. Given the extremely stretchy cartilage joint connecting their jaws to their heads and their ability to extend their windpipe, snorkel-like, outside their mouths, so they can breathe while their mouths are entirely occupied with swallowing—that’s a lot of animals. A 2013 study found that, of a group of marsh rabbits fitted with radio transmitters and released into python territory, 77 percent of those that died within a year had been eaten by pythons. Scientists say that the snakes are responsible for a recent 90 to 99 percent drop in the small mammal population in the national park.

No one knows how many pythons are out there now. Estimates run from 10,000 to perhaps hundreds of thousands. A problem with trying to count them is that they’re what scientists call “cryptic”—hard to detect. Their black-brown-tan camouflage fits perfectly in the marsh, as well as in the higher sandy ground that makes up another part of their range. They are good swimmers and can stay underwater for half an hour or more. Frank Mazzotti, a scientist who has been studying them for more than a decade, told me about a time when he and his colleagues caught a python, attached a radio transmitter for research purposes, and released it. “I was holding the back end of the snake, and the front end was in some shallow water,” Mazzotti said. “I looked and looked, but I could not see the front end of a snake that I was holding onto. That’s when I understood that these snakes were amazing—and we were in trouble.”

The Everglades, a vast subtropical wetland, is unlike any other place on earth. It is essentially a wide, shallow, extremely slow-moving river—sometimes called a “river of grass”—that flows from Lake Okeechobee across the southern quarter of the state. North to south it covers more than a hundred miles. Florida’s porous limestone bedrock provides its floor, and the plants that grew and decayed over millennia have laid down layers of peat on top of that. Stretching for more than 50 miles east to west, the Everglades includes saw grass prairie, pine tree-covered ground, small limestone islands, cypress swamps, and mangrove forests along the ocean.

If the Florida peninsula is a thumb, the Everglades are the thumbnail, and the metro areas of Miami in the east and Naples in the west are the cuticles. Millions of people live in the metro areas, right up to the edges of the Everglades, where, by comparison, there’s hardly anyone. Seminole-Miccosukee Indians, whom the U.S. Army failed to dislodge in the 19th century, occupy several reservations in and around the Everglades. Almost nobody else seems to have figured out how to live in the area without damaging it. When feathers were a fashion rage, a hundred years ago and more, hunters killed a huge number of the region’s birds. Then developers drained millions of acres for agriculture, and caused all kinds of problems with runoff, fires and (in annual dry seasons) dust storms. Sugar cane and other farming led to phosphate pollution, which changed the region’s flora. In the 1970s, it became obvious that environmental degradation of the Everglades threatened South Florida’s water supply, and might eventually make the metro areas unlivable. State and federal agencies enacted large-scale measures, still in progress, to try to improve the situation. Burmese pythons are simply the latest in a series of environmental nightmares we’ve inflicted on the Everglades.

* * *

Snakes, in general, tend to freak people out. Scientists who work with snakes get tired of people who say how much they hate them. But snakes aren’t crazy about people, either. A python’s typical reaction to a human being is to hide or try to get away. As I’ve thought about and observed pythons, I remembered a definition I read somewhere: “Man is a creature of meaningful intentions.” That is true of other living things, especially pythons. They are meaningful intention made flesh, going about their business, doing what they evolved to do. That they happened to fall into an environment ideally suited to them is our fault, not theirs.

All the same, they really should not be here. We Americans can’t agree on much, but most Floridians agree that having large invasive snakes eating up the native wildlife is not a good thing. Given the pythons’ many survival advantages, they will never be eliminated. Today the objective is containment and control.

Ian Bartoszek, a compact, muscular, dark-haired 42-year-old wildlife biologist, lives in Naples and works for the Conservancy of Southwest Florida. Bartoszek has single-handedly caught Burmese pythons that are two and three times as long as he is tall. At the Naples Botanical Gardens, where he was once called to remove a

nine-foot-long python basking on a lawn, the staff refers to him as “the guy who caught the snake with his feet.” When he arrived at the scene, the snake had disappeared into a pond. Bartoszek removed his shoes and socks, waded into the pond, felt around with his feet, located the snake, reached under the surface, grabbed it behind the head and brought it out.

The Conservancy of Southwest Florida is a nonprofit scientific organization that has received funding from the U.S. Geological Survey, the Naples Zoo Conservation Fund and private donors. It works to preserve the original local landscape, along with the native wildlife and plants. By doing this it hopes also to strengthen the area’s resilience in the new extreme weather of climate change. Bartoszek and the rest of his python team—Ian Easterling, 27, and Katie King, 23, who both have backgrounds in snake biology—study and remove the pythons in order to advance science and stay ahead of the invasion.

One morning in early February the three of them led me into the swamps of greater Naples. For orientation, they first showed me satellite images of the region on a computer screen: urban and suburban development here, corporate vegetable farms there, and wild Everglades country extending southward and eastward almost everywhere else, all of it cupped by the dark blue semicircle of the ocean. Since 2013, the conservancy has been tracking what it calls “sentinel snakes.” These are male Burmese pythons in whom radio transmitters have been surgically implanted (placing transmitters outside the body having proved impractical with snakes). The team tracks 23 of these pythons, each signaling at its own radio frequency. Dots on the satellite map indicated where each snake had been heard from last.

Burmese pythons breed between December and March, with February the height of the season. By following the sentinel males, the scientists find breeding females, as well as other males in the females’ company. Removing the females with their eggs—sometimes as many as 60 or even 100-plus eggs per female—is the population-controlling goal. The nonsentinel males are culled, too (or kept and made into sentinels). We parked on a gravel road and plunged into unstable grassy tufts and chest-high forests of saw palmetto whose big, open-handed leaves sounded like cardboard scraping as we pushed through. Bartoszek held up a radio antenna shaped like a horizontal football goal post and listened for beeps. Each sentinel snake has been given a name. “That’s Kirkland,” Bartoszek said, studying the receiver’s dial as the first beeps got louder. Then he heard other beeps. “And that’s Malcolm,” he said. “They’re close to each other. That means the girl they’re after must be nearby.”

The beeps led us into sinkhole country, where we waded up to our pants pockets in swamp water, pulling our booted feet out of gripping muck. Saw grass is pretty, but you can’t grab onto it, because it lacerates your hand. Abundant common reeds, which narrow to an eye-poking point at their tip, are similarly unhelpful. Brazilian peppertrees, an invader that is among Florida’s most damaging flora, also impeded us; they had been sprayed in an attempt to get rid of them, and thorny vines had taken over their dead branches. The vines dangled and ripped at us. Bartoszek chopped at them with his machete.

The beeps coming from Kirkland got so loud that we had to be right on top of him, Bartoszek said. He went ahead by inches, bent over and scanning the swampy, brushy ground. Then suddenly he stood up and said, “Wow! I’ve never seen that before!” Right in front of him, Kirkland had stretched out his entire 13-foot length along a horizontal branch of a mangrove tree, just above eye level. Another few steps and we would have brushed right under him.

The biologist detoured around the tree and searched in waist-deep water on the other side for Kirkland’s female. I moved closer to the snake. In the confusion of leaves and branches, sunlight and shadow, I could hardly make him out. Slowly I approached his head. He did not spook but stayed still. A tiny motion: The tongue flicked out. Like all snakes’ tongues, it was forked; the organ’s double-sidedness helps it determine which direction the molecules it detects are coming from. When the tongue is withdrawn, it touches a sensory node on the roof of the mouth that analyzes the information. Its prominent nostrils resemble retractable headlights; heat-sensing receptors below them enable it to key in on the body temperatures of its mostly warmblooded prey. The small, beadlike eyes were watching, steadily.

No female could be found, nor could Malcolm, the other sentinel nearby. The team agreed that both he and the female had probably gone underwater. In the muck, Bartoszek’s feet felt nothing snaky. So, leaving Kirkland in the tree, we bushwhacked back out. The half-mile we covered, round-trip, took about an hour and a half.

It felt strange to be back so suddenly in Naples traffic on vast expanses of pavement filled with cars. The city’s population explodes with snowbirds this time of year. Listening to the receiver in the truck and on foot, Bartoszek and his colleagues homed in on other sentinels—snakes named Severus, Shrek, Quatro, Stan Lee, Elvis, Harriet, Donnie Darko, Luther and Ender. We battled into the bush to find some of them. Quatro had buried himself in a mass of para grass right next to a housing development and a golf course. The para grass was so thick you could stand on it as if on a mattress. Following the beeps, the scientists parted dense greenery, layer after layer, until they saw the shiny, patterned hide of the huge animal coiled below.

In a sandy environment nearer the ocean, Luther, at 12 feet long, had bunched up into what Bartoszek called “a tight top-hat coil” that looked like a cabbage palm stump. Ian Easterling spotted him, having been fooled by this snake before. “Luther is a really good hider,” Easterling said. Suddenly a hair-raising rattling came from an Eastern diamondback rattlesnake on the ground a few feet away. Katie King, whose specialty is rattlesnakes, reacted ecstatically. Her eyes were like a happy kid’s as she exclaimed over how beautiful the diamondback was.

Meanwhile, Bartoszek had located Luther’s sometime consort, Harriet—one of two transmitter-bearing females the team follows, to learn more about the behavior of female pythons. She had sheltered in a nearby gopher tortoise burrow. Bartoszek put a flexible tube with a camera at its end down the burrow to see if any other snakes were with her. The large, coiled-up snake was alone and stared into the lens, irate. Once, in a similar burrow, he found what’s called a “breeding ball” of pythons. It included a 14-foot-long female and six males. “We were catching snakes so fast, each of us had one in each hand, and I was standing on the others so they couldn’t get away,” Bartoszek said.

The snakes cross boundary lines, so Bartoszek and company do, too. Getting access to state and federal lands, acreage owned by private developers, and dirt tracks through horizon-spanning vegetable farms requires diplomacy, which is a big part of Bartoszek’s job. Tracking Stan Lee, a sentinel who had recently wandered into a farm, Bartoszek got a cheerful wave-through from a farm supervisor. Stan Lee’s beeps came from a marsh beyond long rows of vegetable crops. The snake had last been spotted on the other side of a field of farm equipment. In all likelihood, he had found his way through that field during the last 24 hours, winding among harvesters, gang plows and fertilizer sprayers.

* * *

According to universally known cop lore, undercover police are arrested with the criminals they’ve been investigating, so as not to blow their cover. Not so with sentinel snakes, who are left to identify more targets. The other pythons out there never seem to suspect. Elvis, the longest-surviving sentinel, who is also the longest continuously tracked Burmese python in the world (since 2013), has led the team to 17 other pythons, and has been recaught numerous times to have his transmitter’s battery replaced.

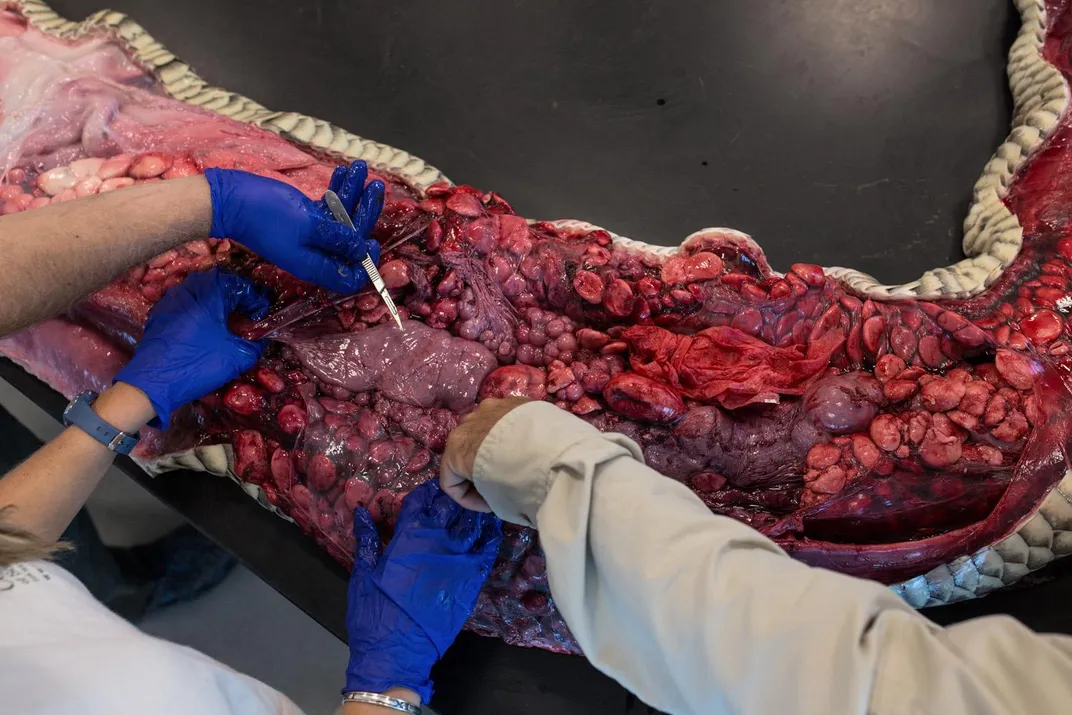

At the conservancy’s science lab, a veterinarian euthanizes the captured nonsentinel snakes with an injection of a drug approved by the American Veterinary Medical Association. Then the snakes go into a freezer for future study. (Later they are incinerated so that nothing ingests the euthanizing chemicals.) One morning Bartoszek invited me to a necropsy of a python the team had captured three weeks before. The snake, a 13-foot, 80-pound female, was in the final thawing stage, piled in coils in and around a metal sink. When I walked in, Bartoszek said, “Twelve thousand five hundred pounds of Burmese pythons have come through that door in the last six years. And we caught all of them within 55 square miles around Naples. The Everglades ecosystem is about 5,000 square miles. Consider that fact when you’re wondering how many pythons might be in the Everglades.”

Easterling and King stretched the python belly-up on the long, marble-topped dissection table. Bartoszek went on, “It is possible that a Burmese python converts about half of the weight of the animals it consumes into its own body mass. So that 12,500 pounds of snake could represent 25,000 pounds of native wildlife—12 1/2 tons of animals and birds taken out of the Southwest Florida ecosystem. If nothing were done about these pythons, they could eventually convert our entire wildlife biomass into one giant snake.”

With a scalpel, Easterling began to slit the snake’s belly, starting just below the chin. He showed me the tongue, a tiny strand of tissue that hardly looked substantial enough to possess such sensitivity. The teeth were horror-movie sharp, and numerous, and they curved inward. Bartoszek and Easterling—and, in fact, most of the people I met who work with pythons in Florida—have been bitten, and the points of python teeth often remain in their fingers, palms or wrists. (Luckily, pythons are not venomous.) As Easterling continued cutting toward the tail and peeling back the hide, the exposed muscle gleamed like pale and massive filet mignon.

The fat tissue resembled marshmallows or balls of mozzarella in bags of clear membrane. This snake, like many pythons caught by the team, had fattened on potentially hundreds of animals until it was bulky in the middle. “We’ve seen pythons so fat that they wobble as they go along the ground,” Easterling said. The long, narrow lungs extended down both sides of the snake. About three-quarters of the way toward the tail, on either side of the cloaca (the single opening for the intestinal, urinary and genital tracts), pythons have small vestigial appendages called spurs. The spurs of males are longer than those of females and provide a quick means of identifying the sex. Back in the mists of evolution, the spurs were legs, and pythons’ ancestors walked on all fours.

Easterling made a rectangular cut in the muscle and removed a small section to send for analysis of its mercury content. Like other apex predators, pythons accumulate toxins in their tissues from what they eat, and a sample can suggest the level of mercury contamination in the environment. He also swabbed the skin to take samples that would be sent to a lab working on experiments with pheromones as lures for monitoring and trapping pythons. Then he removed the eggs, which were about the size of chicken eggs, and leathery. There were 43 of them. Most important, Easterling checked the contents of the digestive tract; he found nothing. (Pythons can go for up to a year without eating.)

Often, undigested animal parts show up: alligator claws, bird feathers (the remains of 37 bird species have been found in pythons’ stomachs), snail shells (probably eaten by prey, because the snakes are not known to eat snails), bobcat claws (larger and solider versions of the claw casings left by cats on a rug) and sometimes the remains of other snakes. Bartoszek brought out a plastic container of hoof cores from white-tailed deer he had found in pythons. Now that the snakes have devastated the population of smaller mammals, they appear to be moving to larger ones. On his computer he called up pictures he had taken last year of a python in the process of swallowing a fawn. “The python weighed 31 pounds, the fawn weighed 35,” he said. “That is, the deer weighed 113 percent as much as the python that was eating it. We believe this is the largest prey-to-Burmese

python ratio ever recorded.”

On an extra-large computer screen overlooking the lab, Bartoszek showed me data points by the hundreds: the current locations of all the sentinel snakes, the sex-seeking routes they had taken during the past weeks, the places where the team had recently captured females, the captures by month during the previous year, the first capture the team ever made, the farthest distance a sentinel is known to have traveled—and more. Were it not for the data Bartoszek’s team has paid for with the sweatiest and swampiest of sweat equity, these cryptic snakes would still be living secret lives in the wilderness, perhaps just across the street. As I left, Bartoszek told me, “We are learning things about Burmese pythons that nobody else on the planet knows.”

* * *

I left Naples and drove eastward across the Everglades. Traffic thronged on Highway 41, the Tamiami Trail. I was headed, eventually, for West Palm Beach, in the northern reaches of Miami, and the headquarters of the South Florida Water Management District, or SFWMD. The Everglades fall under the jurisdiction of various bureaucracies, some of which overlap: the federal government, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the Seminole and Miccosukee Indian tribes, and the SFWMD. In Naples, Bartoszek’s program is mostly privately funded, high-tech and staffed by three people. In the rest of South Florida, the money for python removal is public (or tribal), the number of staff is greater and the emphasis is more on the human factor. In other words, a lot of people just want to go out into the ’Glades and catch some pythons, and these organizations pay them to do that.

The SFWMD, often referred to simply as “the district,” oversees water resources in the southern half of the state, which makes it the most powerful local agency fighting the problem. Since March 2017, its contract hunters have removed more than 2,000 pythons, or more than two and a half miles and 12 tons of snake.

The district’s headquarters occupy a landscaped campus with fountains and a creek. There I met with Rory Feeney, the district’s land resources bureau chief; Amy Peters, its geospatial specialist, who handles its python data; and Mike Kirkland, who runs the Python Elimination Program. They told me that the district is the largest landowner in Florida, that the entire Everglades have been undergoing a $10 billion, 35-year reclamation project, that it’s the largest such project ever attempted in the United States, and that if, when it’s finished, the pythons have eaten all the Everglades’ birds and mammals, it will be an unmitigated disaster.

The fact that Mike Kirkland has the same name as one of Bartoszek’s sentinel snakes is only a coincidence. Kirkland, the person, is another dark-haired, compact, intense combat officer in the python wars. He has one degree in biology and another in environmental policy. The skin of a 17-foot, 3-inch python that he caught himself extends across his office wall. The Python Elimination Program’s 25 contract hunters report to him. They have his cellphone number and he always answers their calls, which often come late at night, because that’s usually the best time for python hunting.

Kirkland’s hunters are an elite. Back in 2013 and again in 2016, the state ran a program called the Python Challenge, which channeled an expressed public wish to help catch pythons. The challenge dispatched hunters into the Everglades by the hundreds—1,500 in 2013, 1,000 in 2016—over a period of several weeks to see what they could do, but the results were disappointing. After that, the district announced it was taking applications to fill 25 full-time paid positions for python hunters. It received 1,000 applications in four days.

Applicants had to show a proven record of success. “Each one has a special gift for seeing snakes,” Kirkland said of the hunters who were selected. He went on, “The Everglades are closed off to most vehicle traffic, but they have levees running through them. We give our hunters master keys to the levee gates. There are hundreds of miles of levee roads they can drive. Snakes like to come up on the levees and bask. The hunters cruise slowly and look for them out the windows, and get cricks in their necks from it. That’s how almost all our pythons are caught—hunters driving the levees. The hunters tell us they love the job and it’s the best job they ever had. They get $8.46 an hour to hunt for up to ten hours a day, and can continue on their own as long as they want after that. We also pay a bonus of $50 per snake, and $25 for every foot of length beyond four feet. Of course, sometimes most of their pay goes for gas money.”

The hunters kill the snakes with shotguns or pistols, or with bolt guns, devices used in slaughterhouses. Often they keep the skins, which can be sold; the rest they leave for scavengers. Working with other agencies and organizations, the district intends to use every method of catching pythons, including heat-sensor drones, pheromone traps, sentinel snakes and snake-hunting dogs. All have drawbacks: The first two are untried and still in development stage; sentinel snakes would come with a risk of their being caught and killed by people who didn’t know they were sentinels; and snake-hunting dogs, which can find pythons more than twice as fast as humans can, are hampered by the heat and the difficulty of the environment. For now, the district will rely on human eyes and hands.

* * *

Donna Kalil, Kirkland’s only woman hunter, told me to meet her in the parking lot of the Miccosukee tribal casino at 5:30 on a weekday afternoon. The casino and its attached hotel sit in the marsh at the western edge of greater Miami, where development ends. Beyond the casino to the northwest is nothing but Everglades. Donna’s vehicle can be seen easily from a distance because it is a Ford Expedition with a snake-spotting tower on top. She was wearing feathery earrings, a long-sleeved green T-shirt that said “Everglades Avengers Python Elimination Team,” and heavy camo pants that were baggy, to give no purchase to a striking snake. Her long, wavy blond hair went almost to her waist. With her were her daughter, Deanna Kalil, who’s a lawyer, and their friend, Pat Jensen. “We’re on a python-hunting girls’ night out,” Donna explained.

She drove west on Highway 41, turned off it, went around some hydraulic infrastructure by a canal and opened a levee gate. Donna has caught more than 140 pythons. Before we started she showed me what to look for. Taking off her python-skin belt, she laid it outstretched in some grass. “You see the way the belt kind of shines?” she asked. “The pattern of the snakeskin looks just like the grass, but the difference is that the skin has a shine. The shine is what you’re looking for.” Then Deanna and I got up in the spotting tower and the truck started rolling along the levee road at a steady 12 miles an hour, with Donna and Pat sticking their heads out the windows on either side.

We drove and we drove—17 miles on one levee, 15 miles on another. Night fell and Donna turned on the truck’s banks of high-beams. To the east, the skyline of Miami sparkled dimly. To the west stretched the total black darkness of the marsh. For a while the lights of planes landing at Miami International passed regularly overhead. Once, when Deanna was flying home from Seattle, her plane crossed the Everglades during daylight and she looked down and saw her mother in the truck driving along a levee.

She and I both held pistol-grip flashlights to point out any snakelike things we saw. I kept calling out to Donna, at the wheel, to stop, because I thought I saw something, but I was always wrong. Soon I got used to the way the shadows of weeds sidled by us as the truck rolled on, and to the dark water suddenly glittering among the grasses, and to the occasional pythonish scraps of PVC pipe. Burrowing owls flared up from the levee sides and flew off, calling. Alligator eyes in the black canals reflected our light back to us like the lantern eyes of demons.

The night got later, and later still. Riding for a while in the cab, I heard some of Donna’s snake-hunting stories—about the python she caught that, when she cut it open, had a domestic cat in its stomach, and about the huge python that came at her with fangs bared and she shot it and it got away and it’s still out there somewhere (“It’s my Moby Dick”), and about the one she caught and then let go of its tail, so she could answer her phone, and in that moment the snake slipped its tail around her neck and started squeezing and would have strangled her if the friend who was riding with her hadn’t pried it off. As she talked, sort of out of the side of her mouth, she kept watching and never broke concentration.

At around midnight she returned me to the casino parking lot, with no snakes caught or seen.

* * *

The next day it rained, and the thermometer dropped into the low 60s. I used the opportunity to visit a high-rise building in Davie, Florida, just northwest of Miami, that’s another python command center. First I talked to Melissa Miller, a quiet, gentle-mannered woman who is the interagency python management coordinator for Florida Fish and Wildlife. She has been working with Burmese pythons since before graduate school, and she wrote her PhD dissertation on parasitic wormlike crustaceans called pentastomes, which live in the pythons’ lungs. The

pentastomes don’t seem to slow the pythons down, but they do appear to affect the health of native snakes who have picked them up. Miller keeps track of the python researchers and hunters that various agencies send into the Everglades and how much hunters get paid for hunting where. According to her data, it takes a hunter an average of 19 hours to find a python.

In an office down the hall, I met Jennifer Ketterlin, an invasive species biologist with the National Park Service. She also is gentle, alert and soft-spoken, a manner maybe derived from watching animals in the wild. She described the challenges of working in the Everglades. In many places the marsh’s limestone bedrock rises into little tree-covered islands called hammocks. These are refuges where female pythons can hide their eggs and stay with them for two months until they hatch. The hammocks, of which there are thousands, can be miles from anywhere and are often accessible only by boat or helicopter. Sometimes the helicopters can’t land; they hover and the scientists jump off. In short, policing the entire Everglades for pythons will never be possible.

On another floor I visited Frank Mazzotti, a professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Florida. He supervises 15 researchers who study the spatial ecology of pythons and other reptiles—that is, where they live and where they go. Python people I had talked to asked me, “Have you met Frank yet?” One of the elders of python studies, he is a tanned, emotive man with a seamed face and a short gray ponytail. “Guys like you get all excited about pythons,” he said after I’d introduced myself. “You reporters come down here and the pythons are all you want to talk about. It’s just sensationalism.” (There is some truth to that. For proof, check out the videos of pythons on YouTube, especially the ones of pythons fighting alligators. Most python coverage plays up their scary side. Still, the videos are pretty cool.)

“What about some of the other invasives, such as the ones that we still have a chance of stopping?” Mazzotti went on. “Like the Argentine black and white tegus, for example. Tegus are lizards that can go into alligator nests and bring out eggs that are bigger than their heads. That’s like you carrying a cantaloupe in your mouth. Just a few tegus can wipe out entire alligator colonies in no time. Fortunately, tegus can also be trapped, so maybe we can still contain them. But nobody wants to hear about that. It was the same with the pythons. People did not have the necessary motivation to do anything about them, either, until it was too late.”

From there Mazzotti moved on to his general take on Florida’s environmental prospects, which he portrayed as dire. Under the current political dispensation more land has been opened to development, more environment-protecting regulations relaxed, more funds cut. As he described it, the influence of real estate and big business in Florida will have a downstream effect that might be of great benefit to pythons, not to mention the tegus.

* * *

You can almost get addicted to looking for pythons. On the next sunny day I went out again with Donna Kalil and we covered I don’t know how many miles, starting at about 8 in the morning. This time we met up with Ryan Ausburn, a fellow contract hunter, at an airboat dock. He is a big man with blue eyes, many tattoos, and a long, narrow chin-beard going gray at the top. Again, Donna drove. Ryan and I manned the spotting tower and he saw details invisible to me—a new, experimental style of military helicopter flying back and forth on the horizon, a turtle shell the size of a golf ball in the wheel ruts. He told me about his previous job as a security guard in a casino in Hollywood, Florida, where he used to watch a bank of two dozen TV screens of closed-circuit feed all night. “Looking for snakes out here is a hell of a lot more fun than watching TV screens shut up in a room,” he said.

We saw more alligators, which splashed enormously and dove into the grasses, and gars finning in the clear pools, and largemouth bass, and egrets, and bitterns, and red-shouldered hawks, and roseate spoonbills, and wood storks (a threatened species, whose remains have been found in python stomachs), and not a single mammal. In puddle-deep tracks next to the levees the endless squiggles of Florida bladderwort, an aquatic plant, kept looking like snakes, and weren’t. We saw no snake of any kind all day. My companions were disappointed, but I said that I was a lifelong fisherman and had plenty of experience not catching anything.

As we drove, the sun went from one end of the sky to the other; eventually Donna took Ryan back to his vehicle and returned me to the Miccosukee casino, where I was handed off to two other contract hunters, Geoff and Robbie Roepstorff, a husband-and-wife team in a new Jeep Rubicon. We kept hunting until past midnight, venturing into spookier country south of Highway 41, among moss-hung trees and strange limestone outcroppings. Again we did not see any pythons. Geoff and Robbie are bankers and hunt pro bono, but take the hunting seriously. Our lack of success made them even more downcast than my previous companions were. Geoff kept telling me that I had to come back in August. “The bugs are terrible, but we can guarantee you a python,” he said.

Maybe the snakes were in remote places, mating. From Naples, Ian Bartoszek kept sending me photos of the snakes his team was catching. Just after I had left, sentinels led them to an 11-foot, 60-pound female, followed over the next few days by a 12-foot, 70-pounder, a 14-foot, 100-pounder, and a 16-foot, 160-pounder—all females. In April, they caught a 17-footer, weighing 140 pounds and carrying 73 eggs. (Half a dozen smaller males had also been caught.) All the photos showed the hunter-scientists in deep swamps. Before long the team had brought in 2,400 pounds of pythons.

In wider herp circles, talk was of Burmese python exploits the likes of which had never been seen. A recent issue of Herpetological Review published two photos of pythons in the Gulf of Mexico, off Florida’s southwestern coast. One had been coiled around the buoy of a crab pot; the crab fishermen who captured it took its picture, then chopped it up for bait. The other photo showed a python before capture, just swimming along. What made the photos remarkable was that the first snake was more than 15 miles offshore. The second was about six miles offshore. Burmese pythons have been known to cross expanses of water in Asia, but none had ever been observed that far out at sea.

How the snakes got there remains unknown. Maybe a storm washed them out of a swamp next to the Gulf. The photos renewed the question of how far the pythons are capable of expanding their range. They do well in heat, and 2015 and 2017 were the first- and second-hottest years in Florida history. As for cold, pythons usually die when temperatures remain under 40 degrees for prolonged periods. During a cold spell in 2010, many pythons and other non-native reptiles throughout South Florida died. The pythons who survived may have taken shelter in the burrows of gopher tortoises or armadillos.

Regarding the possibility of the pythons moving farther north in Florida, Frank Mazzotti told me, “If the climate keeps getting warmer, and enough of them learn to shelter in burrows during cold spells, and they get into that sandy country north of Lake Okeechobee where armadillo and gopher tortoise burrows are more plentiful, then it will be, ‘Katy, bar the door!’”

* * *

According to the ratio of 19 hours of hunting for every python caught, I should have caught one and a half pythons while I was out with the hunters. The fact that I did not even see a python would trouble me if I did not regard the hunting itself as a devotional experience. I scanned the passing Everglades until the details of roadside swampland began to go through my mind in my sleep. The hunters and scientists who search for pythons across South Florida are heroes because they spend thousands of hours truly looking at those details, with mindfulness and quickness of eye.

Nature is a continuity. Staring at screens all day, we usually have no idea what is going on with it. Its wilder parts don’t always stop at the edge of the patio; and the possibility that we might step out the back door and encounter a 17-foot-long apex predator who, to speak plainly, could eat us (pythons have eaten people in other parts of the world), shows poor stewardship, at best. The pros who are out looking for pythons every day fulfill nature’s higher demand that we pay attention.

:focal(2197x532:2198x533)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/4a/8a4a0d0e-74f5-45a9-a654-72a8d2f96597/julaug2019_b07_pythons.jpg)