How A Facebook Experiment Increased Real World Election Turnout

On Election Day 2010, a message displayed on Facebook news feeds drove 340,000 Americans to the polls, according to a new study

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Facebook-like-sign-sized.jpg)

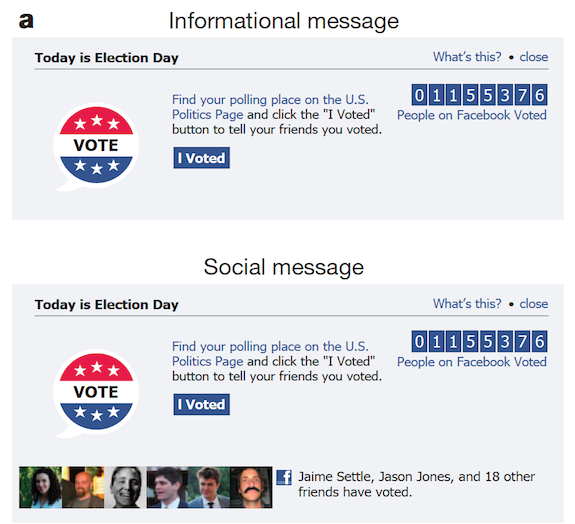

On November 2, 2010, Facebook displayed a non-partisan “get out the vote” banner message at the top of roughly 60 million people’s news feeds, reminding users that it was Election Day. The message allowed them to look up local polling places, click a button to tell their friends that they’d voted, see how many people on Facebook had said they’d voted and see pictures of which of their friends had voted so far.

Unbeknownst to users, though, Facebook tailored the banner message specifically to enable a massive real-world social experiment, as part of a collaboration with researchers from the University of California, San Diego. One percent of the sample—about 600,000 people—saw a similar message, but without the photos of their friends who’d already clicked the “I Voted” button. Another 600,000, serving as a control group, saw no voting message at all.

Now, according to a study published today in Nature, researchers have compared publicly available voting records with the data on Facebook user behavior to determine that the message prompted an estimated 340,000 people to vote who otherwise wouldn’t have. “Voter turnout is incredibly important to the democratic process. Without voters, there’s no democracy,” says UCSD professor James Fowler, lead author of the paper. “Our study suggests that social influence may be the best way to increase voter turnout. Just as importantly, we show that what happens online matters a lot for the ‘real world.’”

The researchers realized that a Facebook user simply clicking “I Voted” didn’t mean they had actually taken the trouble to go to the polls. Instead, they analyzed public voting records, using a computer algorithm to match Facebook accounts with real-world registered voters. In doing so, they used a technique that masked the individual identities of the users once they were matched, preventing Facebook from having access to data indicating which of their users went to the polls.

Once the Facebook accounts were matched with voting registries, the researchers mined the data. What they found was fascinating: Users who saw the full banner message with their friends’ photos included (which the researchers called a “social message”) were 0.39 percent more likely to vote than those who saw no message. When compared with users who saw the banner message without their friends’ photos included (which the researchers called a “informational message”), users who saw the “social message” were still 0.39 percent more likely to vote.

In other words, the key aspect of the message that drove users to the polls was seeing that specific friends had already voted—and without this information, the messages were completely ineffective. “Social influence made all the difference in political mobilization,” Fowler says. “It’s not the ‘I Voted’ button, or the lapel sticker we’ve all seen, that gets out the vote. It’s the person attached to it.” Although 0.39 percent sounds like a tiny number, when extrapolated to the entire sample, it means that the campaign directly led to 60,000 extra votes.

The researchers also examined the indirect effect of the message—whether friends of users who saw the message would be more likely to vote because of real-world social pressure, even if they didn’t see it themselves. Cognizant of the fact that not all Facebook friendships are created equal (we all have Facebook “friends” who we haven’t seen or spoken with in years), they specifically looked at users who had “close friends” who saw the voting message, defining “closeness” by the number of Facebook interactions that occurred between a pair of people, such as tagging photos and sending messages.

When they broke down the data, it turned out that this indirect effect was actually more powerful than the direct impact of the message itself: An estimated 280,000 more votes were cast in the real-world election by users who didn’t see the message but had close friends who did, as compared with those who neither saw the message nor had close friends that did. To figure out why, the researchers conducted interviews with a small sample of users and determined that the vast majority of this increase was due to interactions that occurred with close friends offline—that is, if a close friend saw the “social message,” was motivated to vote and told you that they’d voted in person, you too would become more likely to vote.

Fowler, the author of Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks, feels that the indirect effects of social messaging are often undervalued. “The main driver of behavior change is not the message–it’s the vast social network,” he says. “Whether we want to get out the vote or improve public health, we should not only focus on the direct effect of an intervention but also on the indirect effect as it spreads from person to person to person.”

The research team reports that, along with Facebook, they will continue researching what types of messaging work best in driving people to the polls. So, this Election Day, if you see a message at the top of your news feed, be warned: You might be part of an experiment. Whether you want to vote or not is up to you.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)