How Advertising Shaped the First Opioid Epidemic

And what it can teach us about the second

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/d7/d7d7f166-3063-45f8-bf0c-d0bbf18e2362/vintage-advert-for-medicine.jpg)

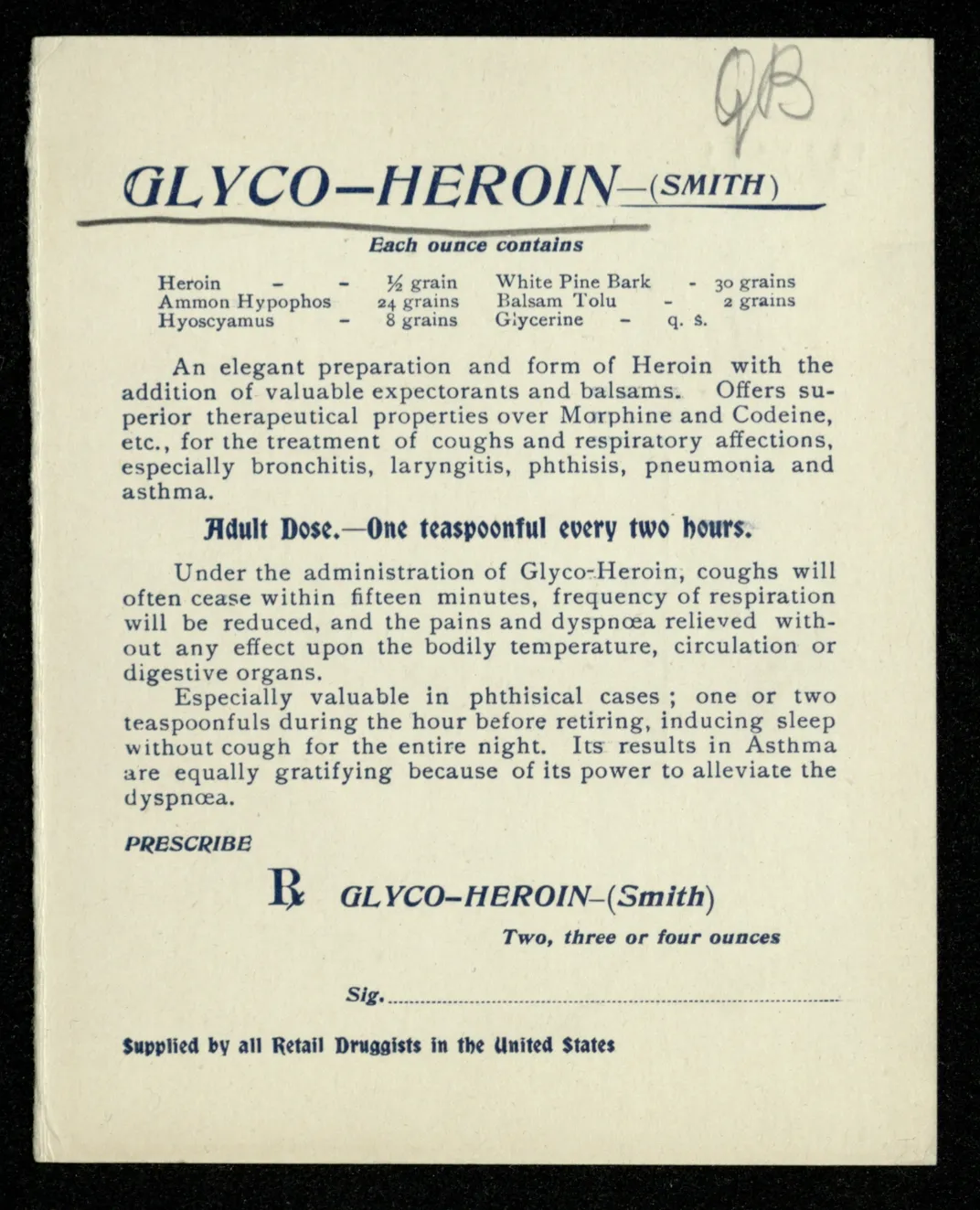

When historians trace back the roots of today’s opioid epidemic, they often find themselves returning to the wave of addiction that swept the U.S. in the late 19th century. That was when physicians first got their hands on morphine: a truly effective treatment for pain, delivered first by tablet and then by the newly invented hypodermic syringe. With no criminal regulations on morphine, opium or heroin, many of these drugs became the "secret ingredient" in readily available, dubiously effective medicines.

In the 19th century, after all, there was no Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to regulate the advertising claims of health products. In such a climate, a popular so-called “patent medicine” market flourished. Manufacturers of these nostrums often made misleading claims and kept their full ingredients list and formulas proprietary, though we now know they often contained cocaine, opium, morphine, alcohol and other intoxicants or toxins.

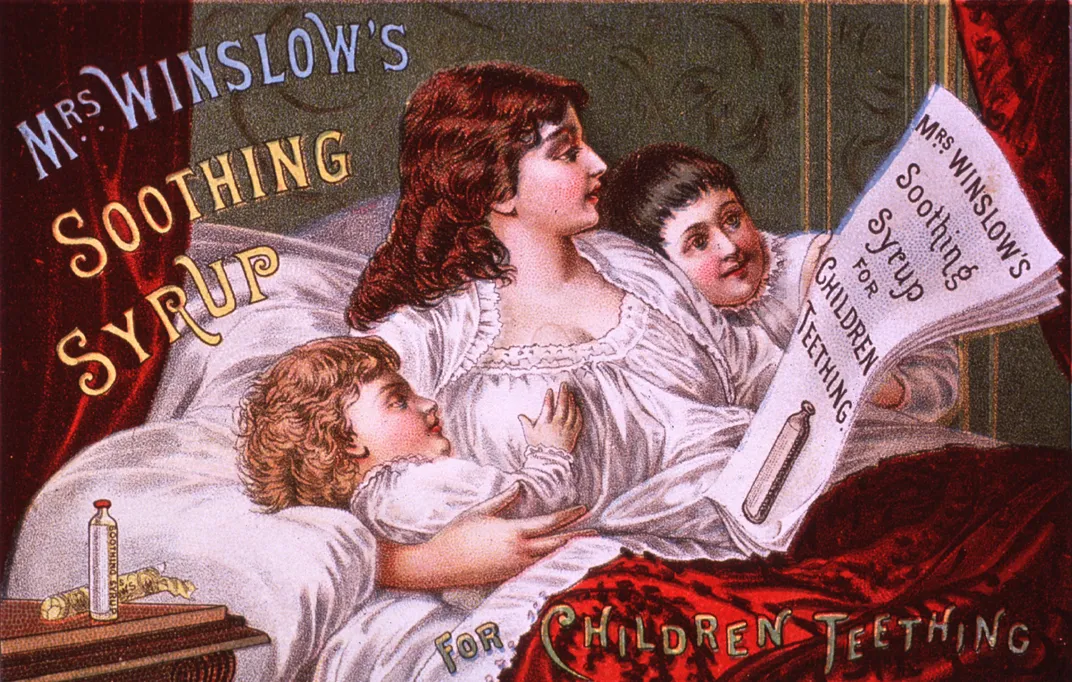

Products like heroin cough drops and cocaine-laced toothache medicine were sold openly and freely over the counter, using colorful advertisements that can be downright shocking to modern eyes. Take this 1885 print ad for Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup for Teething Children, for instance, showing a mother and her two children looking suspiciously beatific. The morphine content may have helped.

Yet while it’s easy to blame patent medicines and American negligence for the start of the first opioid epidemic, the real story is more complicated. First, it would be a mistake to assume that Victorian era Americans were just hunky dory with giving infants morphine syrup. The problem was, they just didn’t know. It took the work of muckraking journalists such as Samuel Hopkins Adams, whose exposé series, “The Great American Fraud” appeared in Colliers from 1905 to 1906, to pull back the curtain.

But more than that, widespread opiate use in Victorian America didn’t start with the patent medicines. It started with doctors.

The Origins of Addiction

Patent medicines typically contained relatively small quantities of morphine and other drugs, says David Herzberg, a professor of history at SUNY-University at Buffalo. “It’s pretty well recognized that none of those products produced any addiction,” says Herzberg, who is currently writing a history of legal narcotics in America.

Until the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914, there were no federal laws regulating drugs such as morphine or cocaine. Moreover, even in those states that had regulations on the sale of narcotics beginning in the 1880s, Herzberg notes that “laws were not part of the criminal code, instead they were part of medical/pharmacy regulations.”

The laws that existed weren't well-enforced. Unlike today, a person addicted to morphine could take the same “tattered old prescription” back to a compliant druggist again and again for a refill, says David Courtwright, a historian of drug use and policy at the University of North Florida.

And for certain ailments, patent medicines could be highly effective, he adds. “Quite apart from the placebo effect, a patent medicine might contain a drug like opium,” says Courtwright, whose book Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America, provides much of the original scholarship in this area. “If buyers took a spoonful because they had, say, a case of the runs, the medicine probably worked.” (After all, he points out, “opium is a constipating agent.”)

Patent medicines may not have been as safe as we would demand today or live up to claims of panacea, but when it came to coughs and diarrhea, they probably got the job done. “Those drugs are really famous, and they do speak to a time where markets were a little bit out of control,” Herzberg says. "But the vast majority of addiction during their heyday was caused by physicians.”

Marketing to Doctors

For 19th century physicians, cures were hard to come by. But beginning in 1805, they were handed a way to reliably make patients feel better. That’s the year German pharmacist Friedeich Serturner isolated morphine from opium, the first “opiate” (the term opioid once referred to purely synthetic morphine like drugs, Courtwright notes, before becoming a catchall covering even those drugs derived from opium).

Delivered by tablet, topically and, by mid-century, through the newly invented hypodermic syringe, morphine quickly made itself indispensable. Widespread use by soldiers during the Civil War also helped trigger the epidemic, as Erick Trickey reports in Smithsonian.com. By the 1870s, morphine became something of “a magic wand [doctors] could wave to make painful symptoms temporarily go away,” says Courtwright.

Doctors used morphine liberally to treat everything from the pain of war wounds to menstrual cramps. “It’s clear that that was the primary driver of the epidemic,” Courtwright says. And 19th century surveys Courtwright studied showed most opiate addicts to be female, white, middle-aged, and of “respectable social background”—in other words, precisely the kind of people who might seek out physicians with the latest tools.

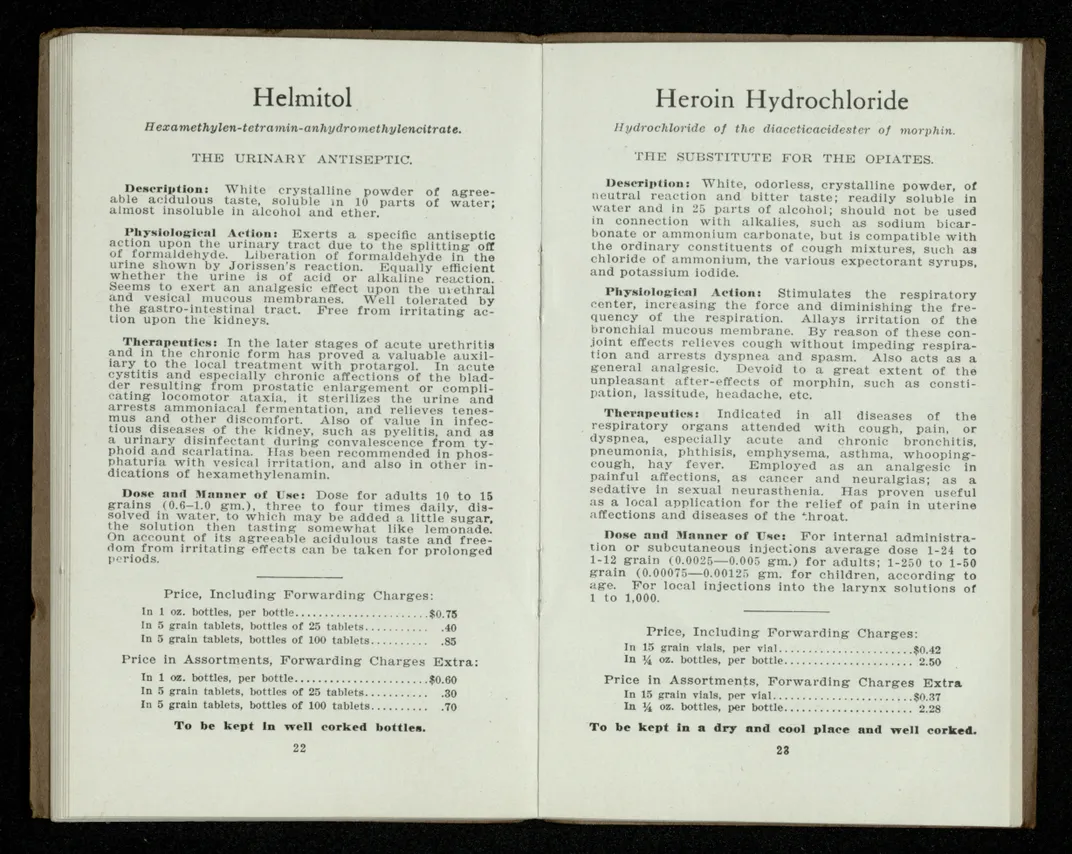

Industry was quick to make sure physicians knew about the latest tools. Ads for morphine tablets ran in medical trade journals, Courtwright says, and, in a maneuver with echoes today, industry sales people distributed pamphlets to physicians. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Historical Medical Library has a collection of such “medical trade ephemera” that includes a 1910 pamphlet from The Bayer Company titled, “The Substitute for the Opiates.”

The substitute? Heroin hydrochloride, at the time a new drug initially believed to be less addictive than morphine. Pamphlets from the Antikamnia Chemical Company, circa 1895 show an easy cheat sheet catalog of the company’s wares, from quinine tablets to codeine and heroin tablets.

Physicians and pharmacists were the key drivers in increasing America's per capita consumption of drugs like morphine by threefold in the 1870s and 80s, Courtwright writes in a 2015 paper for the New England Journal of Medicine. But it was also physicians and pharmacists who ultimately helped bring the crisis back under control.

In 1889, Boston physician James Adams estimated that about 150,000 Americans were "medical addicts": those addicted through morphine or some other prescribed opiate rather than through recreational use such as smoking opium. Physicians like Adams began encouraging their colleagues to prescribe “newer, non-opiate analgesics,” drugs that did not lead to depression, constipation and addiction.

“By 1900, doctors had been thoroughly warned and younger, more recently trained doctors were creating fewer addicts than those trained in the mid-nineteenth century,” writes Courtwright.

This was a conversation had between doctors, and between doctors and industry. Unlike today, drug makers did not market directly to the public and took pride in that contrast with the patent medicine manufacturers, Herzberg says. “They called themselves the ethical drug industry and they would only advertise to physicians.”

But that would begin to change in the early 20th century, driven in part by a backlash to the marketing efforts of the 19th century patent medicine peddlers.

Marketing to the Masses

In 1906, reporting like Adams’ helped drum up support for the Pure Food and Drug Act. That gave rise to what would become the Food and Drug Administration, as well as the notion that food and drug products should be labeled with their ingredients so consumers could make reasoned choices.

That idea shapes federal policy right up until today, says Jeremy Greene, a colleague of Herzberg’s and a professor of the history of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine: “That path-dependent story is part of the reason why we are one of the only countries in the world that allows direct-to-consumer advertising," he says.

At the same time, in the 1950s and 60s, pharmaceutical promotion became more creative, coevolving with the new regulatory landscape, according to Herzberg. As regulators have set out the game, he says, “Pharma has regularly figured out how to play that game in ways that benefit them.

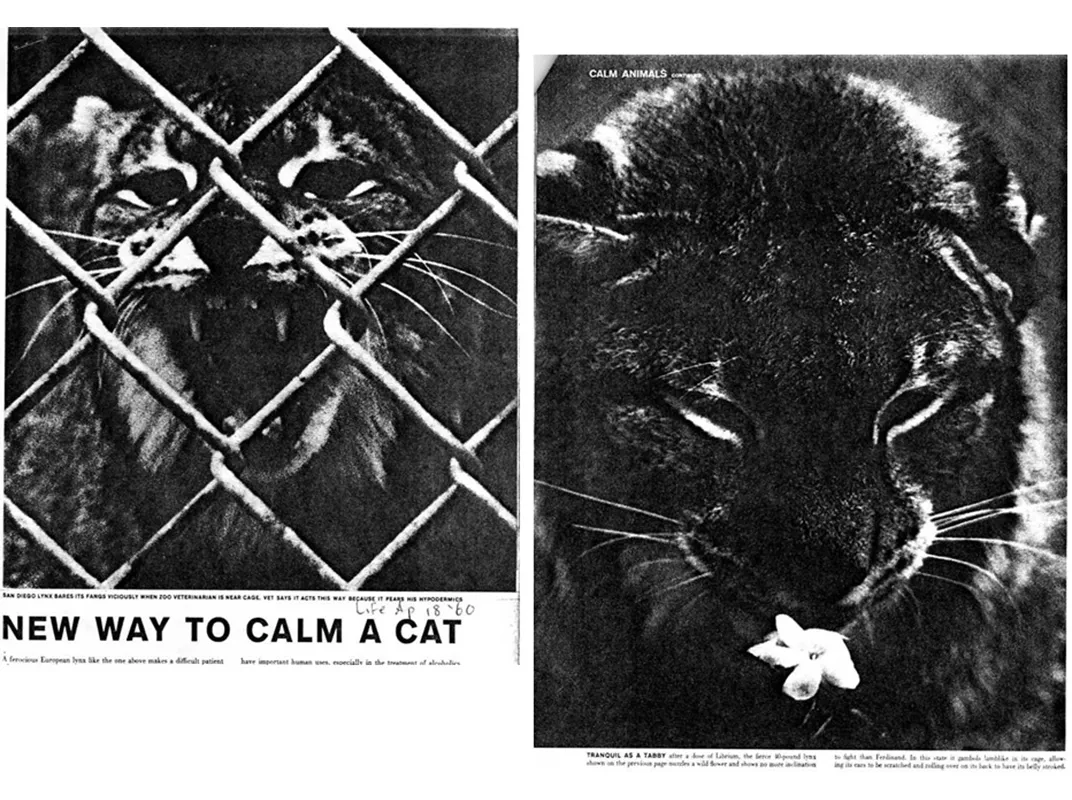

Though the tradition of eschewing direct marketing to the public continued, advertising in medical journals increased. So, too, did more unorthodox methods. Companies staged attention-grabbing gimmicks, such as Carter Products commissioning Salvador Dali to make a sculpture promoting its tranquilizer, Miltown, for a conference. Competitor Roche Pharmaceuticals invited reporters to watch as its tranquilizer Librium was used to sedate a wild lynx.

Alternatively, some began taking their messaging straight to the press.

“You would feed one of your friendly journalists the most outlandishly hyped-up promise of what your drug could do,” Greene says. “Then there is no peer review. There is no one checking to if see it’s true; it’s journalism!” In their article, Greene and Herzberg detail how ostensibly independent freelance science journalists were actually on the industry payroll, penning stories about new wonder drugs for popular magazines long before native advertising became a thing.

One prolific writer, Donald Cooley, wrote articles with headlines such as “Will Wonder Drugs Never Cease!” for magazines like Better Homes and Garden and Cosmopolitan. “Don’t confuse the new drugs with sedatives, sleeping pills, barbiturates or a cure,” Cooley wrote in an article titled “The New Nerve Pills and Your Health.” “Do realize they help the average person relax.”

As Herzberg and Greene documented in a 2010 article in the American Journal of Public Health, Cooley was actually one of a stable of writers commissioned by the Medical and Pharmaceutical Information Bureau, a public relations firm, working for the industry. In a discovery Herzberg plans to detail in an upcoming book, it turns out there is “a rich history of companies knocking at the door, trying to claim that new narcotics are in fact non-addictive” and running advertisements in medical trade journals that get swatted down by federal authorities.

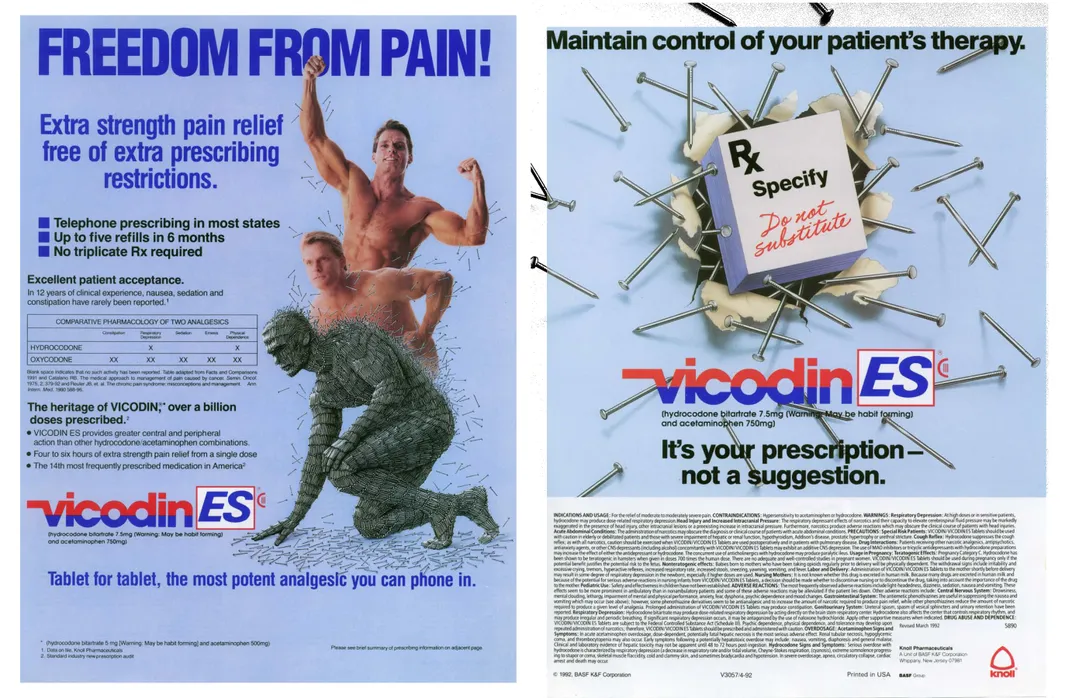

A 1932 ad in the Montgomery Advertiser, for instance, teases a new “pain relieving drug, five times as potent as morphine, as harmless as water and with no habit forming qualities.” This compound, “di-hydro-mophinone-hydrochlorid” is better known by the brand name Dilaudid, and is most definitely habit forming, according to Dr. Caleb Alexander, co-director of the Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness at Johns Hopkins.

And while it’s not clear if the manufacturer truly believed it was harmless, Alexander says it illustrates the danger credulity presents when it comes to drug development. “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is,” he says. “It is this sort of thinking, decades later, that has driven the epidemic."

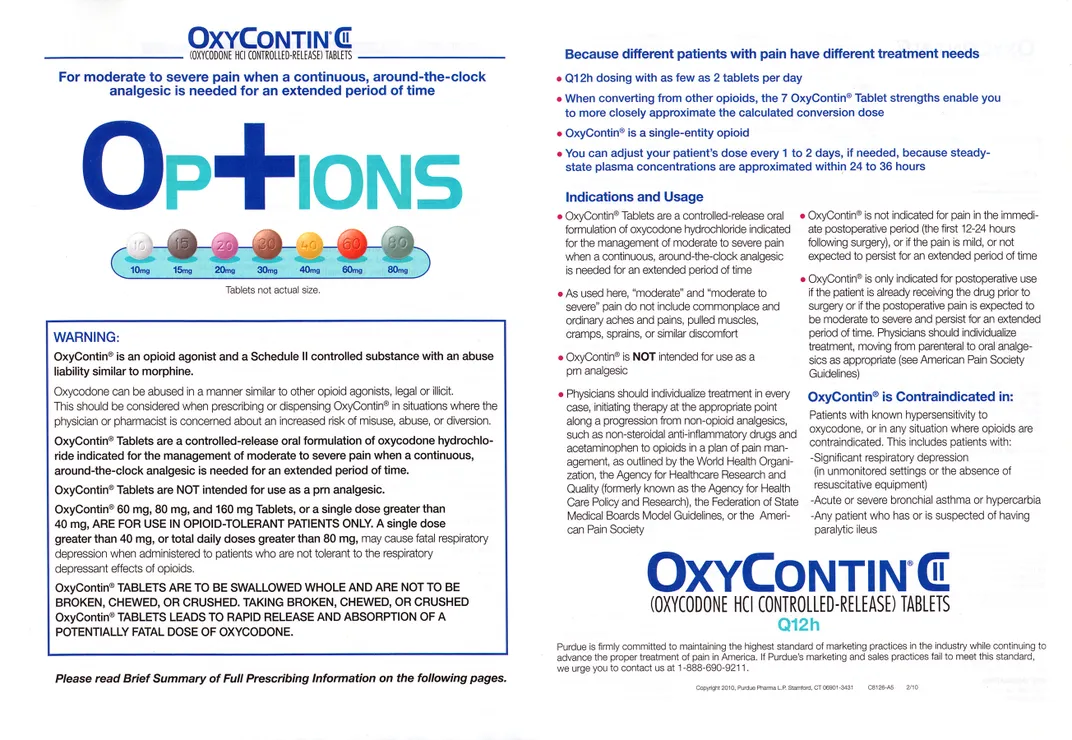

It wasn’t until 1995, when Purdue Pharma successfully introduced OxyContin, that one of these attempts was successful, says Herzberg. “OxyContin passed because it was claimed to be a new, less-addictive type of drug, but the substance itself had been swatted down repeatedly by authorities since the 1940s,” he says. OxyContin is simply oxycodone, developed in 1917, in a time-release formulation Purdue argued allowed a single dose to last 12 hours, mitigating the potential for addiction.

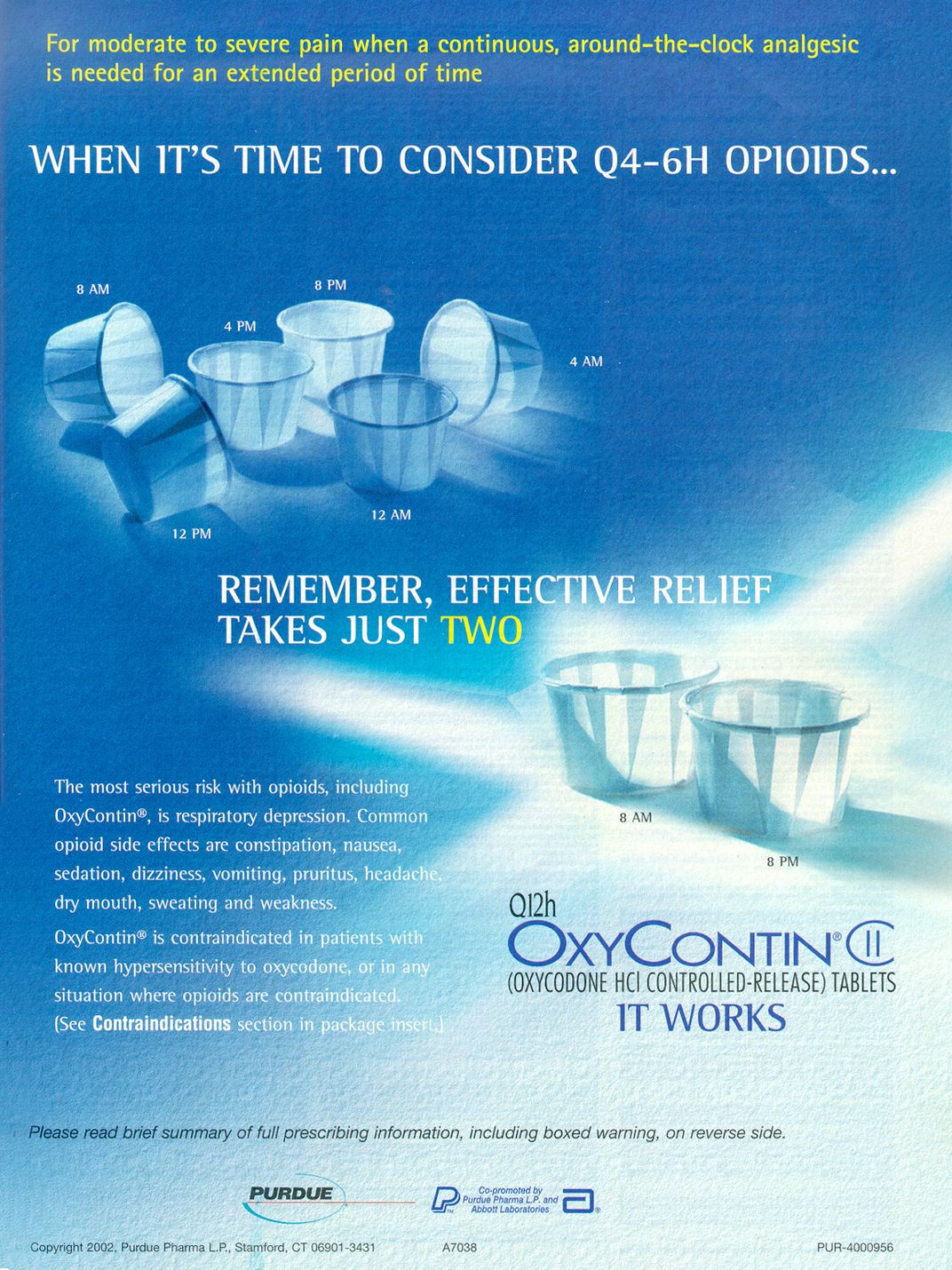

Ads targeting physicians bore the tagline, “Remember, effective relief just takes two.”

“If OxyContin had been proposed as a drug in 1957 authorities would have laughed and said no,” Herzberg says.

Captivating the Consumer

In 1997, the FDA changed its advertising guidelines to open the door to direct-to-consumer marketing of drugs by the pharmaceutical industry. There were a number of reasons for this reversal of more than a century of practice, Greene and Herzberg say, from the ongoing ripples of the Reagan-era wave of deregulation, to the advent of the “blockbuster” pharmaceutical, to advocacy by AIDS patients rights groups.

The consequences were profound: a surge of industry spending on print and television advertising describing non-opioid drugs to the public that hit a peak of $3.3 billion in 2006. And while ads for opioid drugs were typically not shown on television, Greene says the cultural and political shifts that made direct-to-consumer advertising possible also changed the reception to the persistent pushing of opioids by industry.

Once again, it was not the public, but physicians that were the targets of opioid marketing, and this was often quite aggressive. The advertising campaign for OxyContin, for instance, was in many ways unprecedented.

Purdue Pharma provided physicians with starter coupons that gave patients a free seven to 30-day supply of the drug . The company's sales force—which more than doubled in size from 1996 to 2000—handed doctors OxyContin-branded swag including fishing hats and plush toys. A music CD was distributed with the title “Get in the Swing with OxyContin.” Prescriptions for OxyContin for non-cancer related pain boomed from 670,000 written in 1997, to 6.2 million in 2002.

But even this aggressive marketing campaign was in many ways just the smoke. The real fire, Alexander argues, was a behind-the-scenes effort to establish a more lax attitude toward prescribing opioid medications generally, one which made regulators and physicians alike more accepting of OxyContin.

“When I was in residency training, we were taught that one needn’t worry about the addictive potential of opioids if a patient had true pain,” he says. Physicians were cultivated to overestimate the effectiveness of opioids for treating chronic, non-cancer pain, while underestimating the risks, and Alexander argues this was no accident.

Purdue Pharma funded more than 20,000 educational programs designed to promote the use of opioids for chronic pain other than cancer, and provided financial support for groups such as the American Pain Society. That society, in turn, launched a campaign calling pain “the fifth vital sign,” which helped contribute to the perception there was a medical consensus that opioids were under, not over-prescribed.

.....

Are there lessons that can be drawn from all this? Herzberg thinks so, starting with the understanding that “gray area” marketing is more problematic than open advertising. People complain about direct-to-consumer advertising, but if there must be drug marketing, “I say keep those ads and get rid of all the rest," he says, "because at least those ads have to tell the truth, at least so far as we can establish what that is.”

Even better, Herzberg says, would be to ban the marketing of controlled narcotics, stimulants and sedatives altogether. “This could be done administratively with existing drug laws, I believe, based on the DEA’s power to license the manufacturers of controlled substances.” The point, he says, would not be to restrict access to such medications for those who need them, but to subtract “an evangelical effort to expand their use.”

Another lesson from history, Courtwright says, is that physicians can be retrained. If physicians in the late 19th century learned to be judicious with morphine, physicians today can relearn that lesson with the wide array of opioids now available.

That won’t fix everything, he notes, especially given the vast black market that did not exist at the turn of the previous century, but it’s a proven start. As Courtwright puts it: Addiction is a highway with a lot of on-ramps, and prescription opioids are one of them. If we remove the billboards advertising the exit, maybe we can reduce, if not eliminate the number of travelers.

“That’s how things work in public health,” he says. “Reduction is the name of the game.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/2e/8c2e23e3-0435-453c-8506-9065e613f101/winslows_syrup.jpg)