How California’s Giant Sequoias Tell the Story of Americans’ Conflicted Relationship With Nature

In the mid-19th century, “Big Tree mania” spread across the country and our love for the trees has never abated

In the winter of 1852, while chasing a wounded grizzly bear in the mountains of eastern California, a hunter named Augustus T. Dowd encountered a very large tree. It had red-orange bark and clouds of sea-green needles, and it would’ve taken more than a dozen men with outstretched arms to encircle it. When Dowd told his campmates what he’d found, they laughed. Then he took them to see the tree.

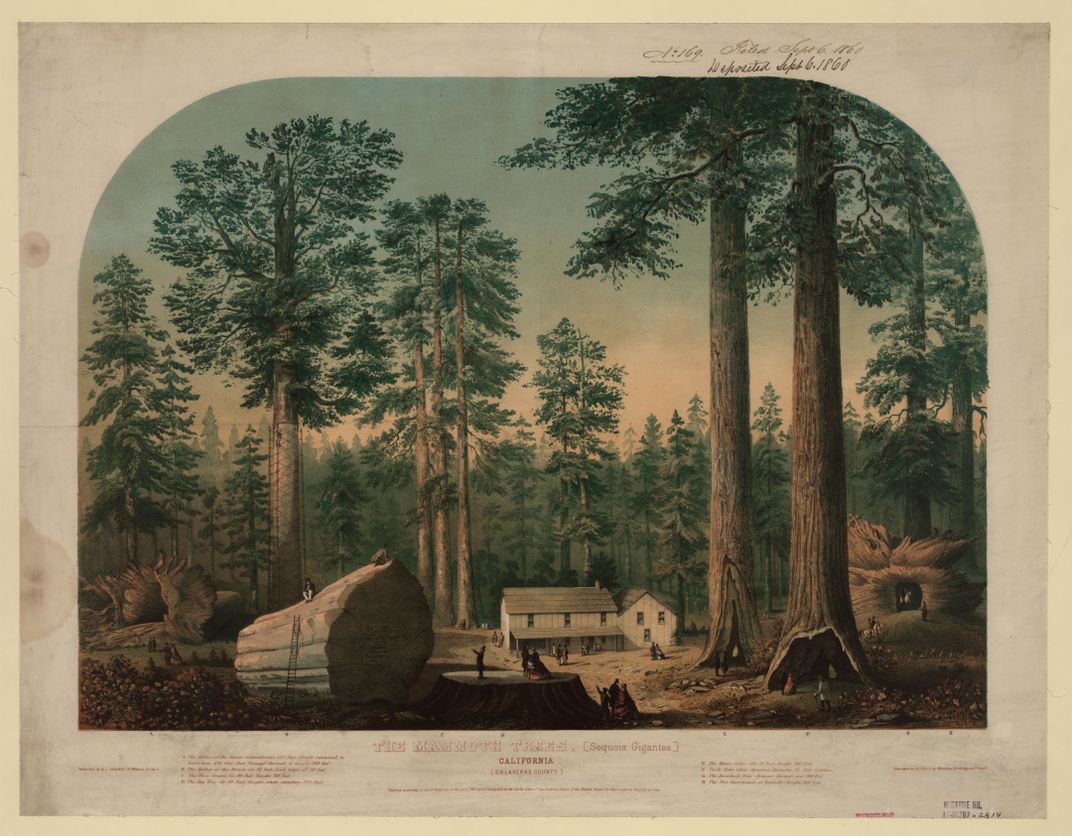

Newspapers trumpeted the discovery, calling the find—long known to Native Americans—“the Sylvan Mastodon” and “the Vegetable Monster.” Soon, another group of men returned to Dowd’s tree and, perhaps inevitably, cut it down. Everybody counted the rings on the felled trunk differently—one reporter estimated it to be 2,500 years old, another 4,000 and a third 6,500. “It must have been a little plant when Samson was slaying the Philistines,” one wrote.

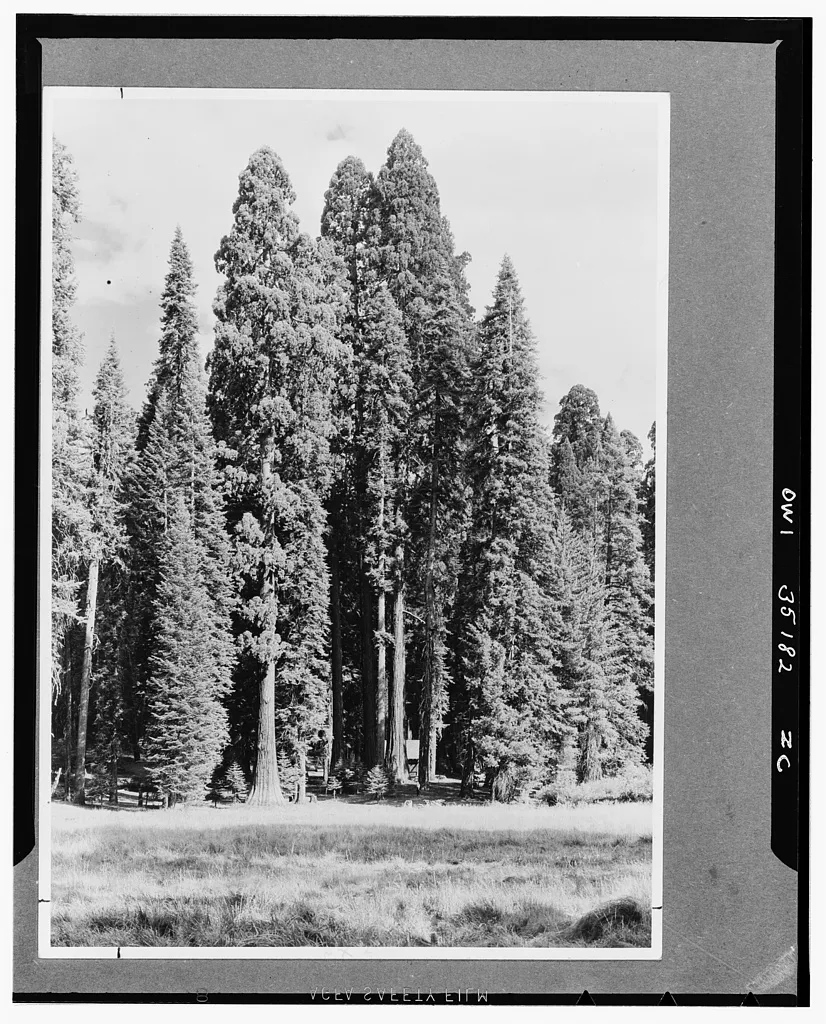

In fact, the tree in question was only about 1,200 years old, relatively young for one of the earth’s longest living and largest species. The astounding trees we now know as giant sequoias can live for more than 3,000 years and grow to some 300 feet, and the superlative species inspired this young, growing nation like no other living thing. That it is rare and limited in its range—the tree lives in only about 70 groves in the middle elevations of the Sierra Nevada—made it all the more fascinating. For more than 150 years, the “noblest tree-species in the world,” as the great naturalist John Muir called it, has been a symbol of America’s grandeur, our fraught relationship with nature and our fears about the future.

The nation had only recently seized California from Mexico when Dowd made his discovery, and the ancient giants were the upstart nation’s answer to the Old World’s cathedrals. California, one 1853 article predicted, “will yet be found not only to surpass the rest of the world in the extent and abundance of her gold and the magnitude of her trees, but in her natural bridges, her mammoth caves and her Niagaras.”

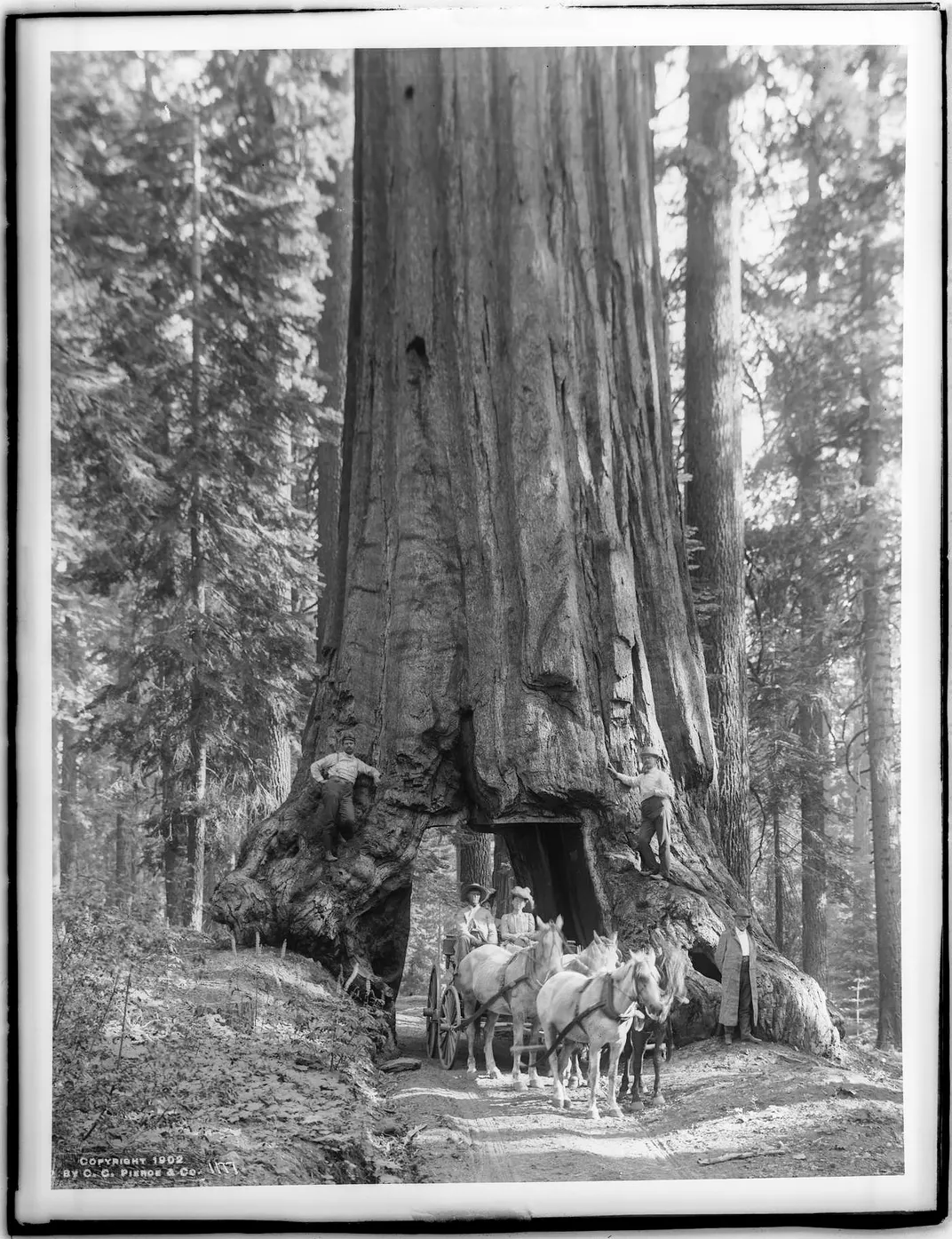

“Big Tree mania” set in, William Tweed writes in a 2016 history of the giant sequoia. Pieces of Dowd’s tree went on tour to San Francisco and to New York City. By 1855, a hotel had been built in the grove. Later, promoters cut a wide passage in the base of one giant and charged for carriage rides through it. Souvenirs proliferated—candlesticks and canes turned from sequoia wood, packets of sequoia seeds, hotel postcards and stereoscope images. A collection of giant sequoia memorabilia, recently acquired by Stanford University, serves as a snapshot of the country’s obsession and the impulse to cash in on it.

King Sequoia: The Tree That Inspired a Nation, Created Our National Park System, and Changed the Way We Think about Nature

From a towering tree, one of California's preeminent naturalists unspools a history that echoes across generations and continents. Former park ranger William C. Tweed takes readers on a tour of the Big Trees in a narrative that travels deep into the Sierras, around the West, and all the way to New Zealand; and in doing so he explores the American public's evolving relationship with sequoias.

Timbermen toppled the giant sequoias, one by one, and then by the groveful. By the end of the 19th century, the American frontier was closed, the herds of buffalo and the great flocks of passenger pigeons were gone, and some feared the magnificent trees would disappear, too. Nature could be used and used up. But the idea of conservation had taken root. Two of the first three national parks were created to protect the sequoias.

Such rescue attempts had unintended consequences. Early conservationists suppressed fires, which they thought damaged the sequoias. In truth, the trees needed nature’s regular, low-burning blazes to thin their competition and to clear ground for their seedlings. Decades of fire suppression left the groves packed with vegetation that could fuel bigger, more damaging fires, like the one that swept into Kings Canyon in 2015, killing approximately ten large sequoias. Grove managers have worked to return the habitat to a more natural state since the 1960s but say many sequoia groves remain overgrown and at risk.

Our fascination with these giants hasn’t diminished since the days of Big Tree mania. In 2014, more than a million people visited the Mariposa Grove in Yosemite National Park, home to approximately 500 giant sequoias. Vehicles and parking lots and concrete paths were encroaching on the trees’ habitat. The grove was closed in 2015 for restoration; it will reopen this spring.

But there is a problem more insidious than sneaker-clad tourists: climate change. In 2014, after two years of drought, many sequoias began losing their needles. Nobody alive had ever seen this before. It seemed like another sign of the times, a losing struggle to save even the rarest and best of things. “In 50 years, the whole population could be in trouble,” one researcher told the New York Times.

When the snows and rains came in 2017 and ended the drought, the sequoias were still standing. The trees, it now seems, had shed their needles as a way to reduce their need for water. Last summer, the needles began to grow back, and with them our hopes for the sequoias. But with temperatures rising and weather patterns changing, their future is as uncertain as it was in Muir’s day. “God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand storms,” he wrote in the early 1900s. “But he cannot save them from sawmills and fools; this is left to the American people.”

Into the Woods

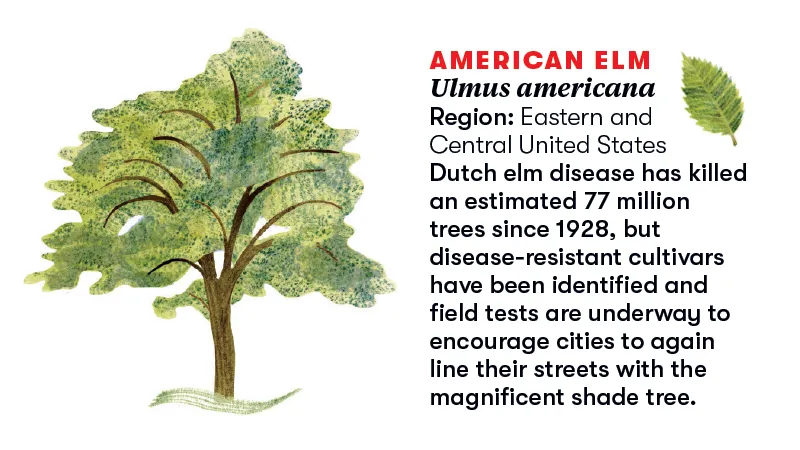

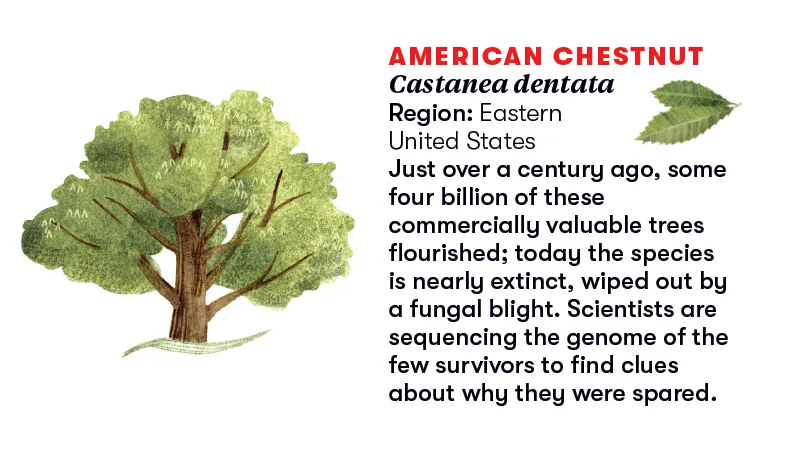

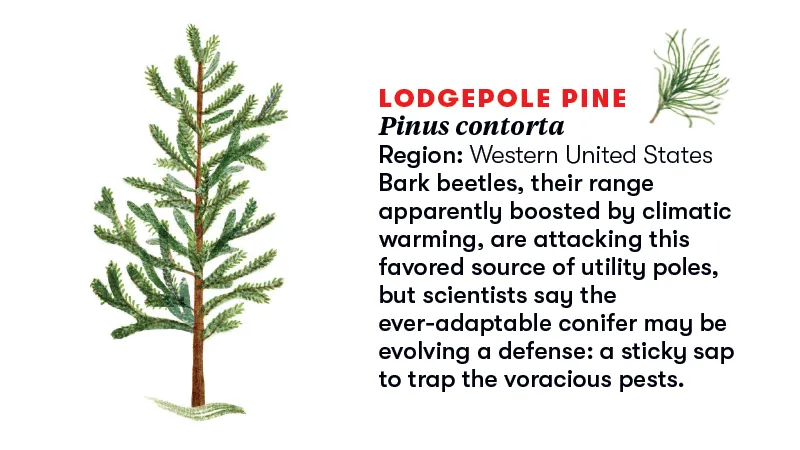

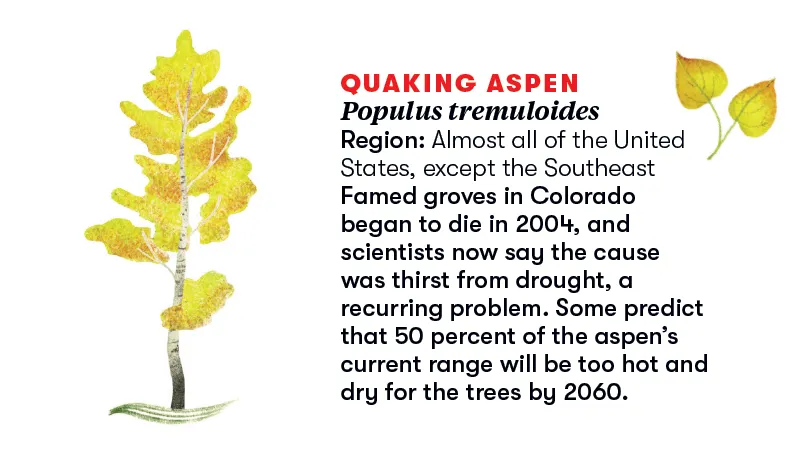

Some of the United States’ 228 billion trees are doing better than others. The rise and fall of our most beloved varieties.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.