How Do Crabs See Food on the Ocean Floor? UV Vision

Marine biologists took a submersible more than half a mile below the surface to understand the strange creatures that glow on the ocean floor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/6d/bc6d7a20-a836-4100-88ab-42430ba7c412/gastroptychus-spinifer-2.jpg)

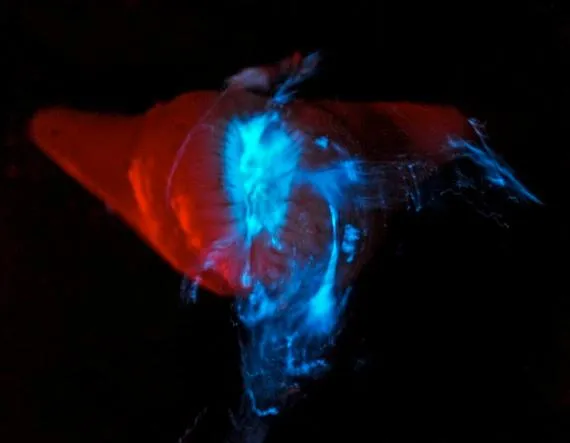

A few years ago, when Tamara Frank, Sönke Johnsen and Thomas Cronin, a team of marine biologists, descended nearly half a mile to the ocean floor near the Bahamas in a tiny submersible, they were fairly stunned by what they saw: close to nothing. “We were surprised by how little bioluminescence is down there,” Frank told LiveScience. In one of the world’s first explorations of bioluminescence on the deep ocean floor, they found that, unlike in the open ocean, where scientists estimate that 90 percent of organisms produce bioluminescent light, just 10 to 20 percent of the creatures at the bottom of the ocean (mainly plankton) were capable of glowing.

When the team parked the submersible, shut the lights off and simply observed, though, they were amazed. “If you sit there with the lights out, you’ll see this little light show as plankton run into different habitats,” Johnsen said. “There is no substitute for actually being in that habitat to understand what it’s like to be those animals.” Over time, they identified several organisms that no one expected to glow that were generating light, including coral, starfish, sea cucumbers and the first-ever bioluminescent sea anemone, as described in a study published yesterday in The Journal of Experimental Biology.

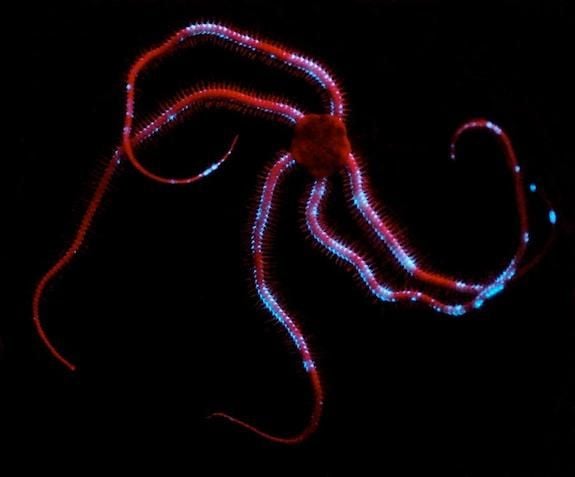

They also discovered that the several species of crabs inhabiting the ocean floor had a very unusual characteristic: As described in a concurrent paper published in the same journal, they found the first crabs ever identified as capable of seeing ultraviolet (UV) light.

While measuring the wavelengths of light produced by each of the organisms, the team noticed in particular the crabs’ skill at grasping plankton and other food to eat. “They just hang out in these plantlike things, and every so often—they have these amazingly long claws—they reach over and they’re clearly picking something off and bringing it to their mouths,” Frank said.

Intrigued, they tested the crabs’ vision for themselves. Using special equipment on the submersible, they suctioned the creatures into light-tight containers and brought them to the surface, then conducted an experiment aboard their ship. Flashing various colors and intensities of light at the crabs while using electrodes to monitor their eye movement, Frank discovered that all seven species tested were capable of seeing blue light. This wasn’t particularly surprising, as blue is the only color of light that can naturally penetrate down to the ocean floor as all other colors are filtered out by the water.

The second part of the experiment, though, was rather surprising. Two of the crab species they found, Eumunida picta and Gastroptychus spinifer, also moved their eyes in a way that indicated they could see green and ultraviolet light.

This raised an immediate question. “There is absolutely no UV and violet light coming down at that depth; it’s long gone,” said Johnsen. In that case, why on earth would the crabs have evolved to be capable of seeing it? Scientists have long assumed that organisms living on the nearly pitch black sea floor were colorblind, since there is so little color to be seen.

Their answer, for now, is only a hypothesis—but an extremely compelling one. “Call it color-coding your food,” said Johnsen. If the creatures can see green, blue and ultraviolet light, they might be capable of distinguishing between UV-emitting anemones and green-glowing toxic corals (which are not safe to eat) and blue-glowing plankton (which are the crabs’ primary food source).

“It is only a hypothesis. We could be wrong,” Johnsen said. “But we can’t think of another reason why an animal would use this ability to see UV and violet light because there isn’t solar light left."

Part of the reason we know so little about the seafloor environment, he says, is because of the difficulty in getting the funding for and access to a submersible necessary to conduct these sorts of observations. The researchers, though, say that learning about this habitat is a crucial first step in building support to protect it.

“The sea floor is three quarters of the earth’s area and the water column is over 99 percent of the earth’s liveable space, yet we know less about it than the surface of the moon,” Johnsen told the BBC. “I think people will only protect what they love, and they’ll only love what they know. So part of our job is to show people what’s down there.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)