How Fetus Dissections in the Victorian Era Helped Shape Today’s Abortion Wars

Besides teaching us about disease and human development, they molded modern attitudes of the fetus as distinct entity from the mother

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/2b/712baf55-0715-46be-9761-94a5ce34de97/118710_web.jpg)

On June 27, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down parts of a Texas law that severely restricted abortion clinics in the state, reigniting the national debate over a fetus’ right to life. The historic ruling, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellersted, raised familiar heckles on both sides of the argument: Pro-choice advocates rallied in defense of a woman’s control over her body, while pro-life advocates argue against what they believed was a shameful disregard for life before birth.

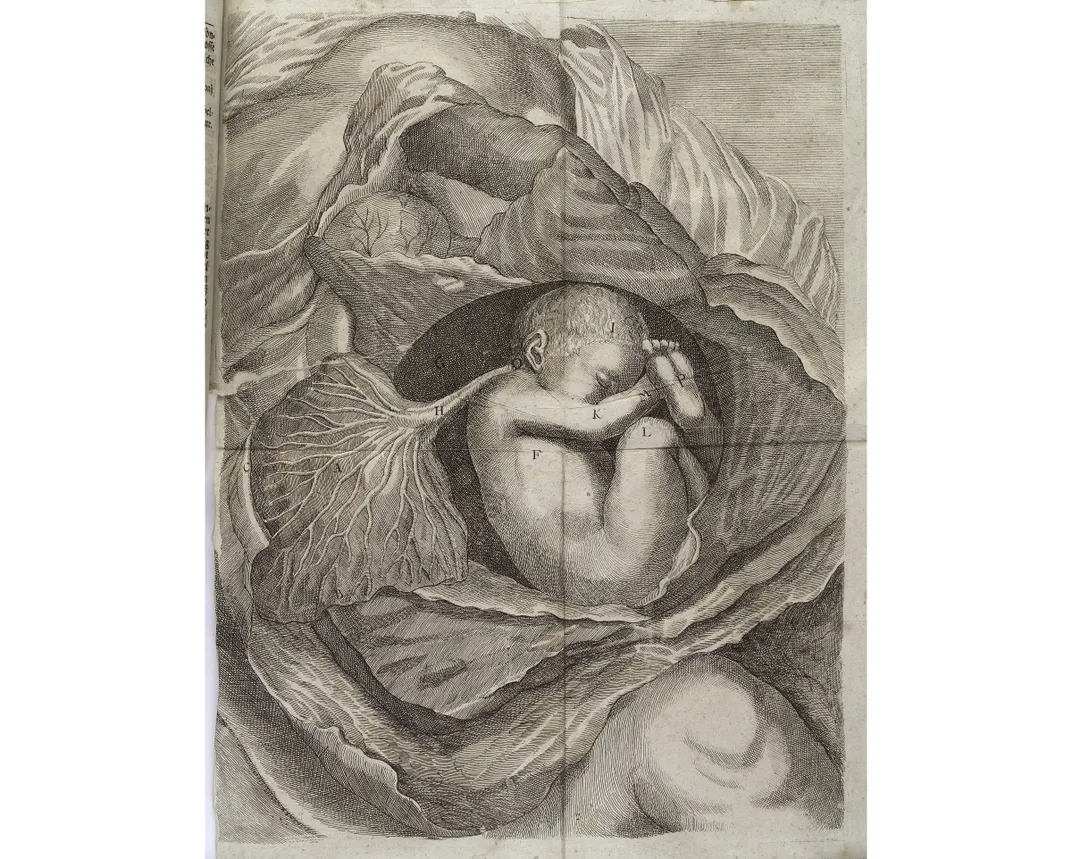

Strange as it may seem, the outrage that fuels both sides of this debate owes itself to a long history of medical dissections of infants and fetuses that brings to mind last year's Planned Parenthood fetal tissue scandals. These dissections yielded much of the information we now know about how humans change from kidney bean-sized creatures to full-grown people, and helped shape the current conceptions of the embryo as a nascent being, completely distinct from the mother.

“Nowadays it looks shocking to us that infants were ever dissected,” says Lynn Morgan, author of Icons of Life: A Cultural History of Human Embryos. “But when we think about it, it was the fact that infants were dissected that made it possible for us to be shocked about it today.”

A study published in the Journal of Anatomy last month sheds light on the hidden history of these dissections in Victorian England. The researchers analyzed 54 infant skulls dating from 1768 to 1913 that were recently found to be dissection subjects in the Cambridge collections. They found that, unlike the adult specimens, the infants and fetuses were largely preserved intact—suggesting that they were more scientifically important in these early years of anatomy study than previously believed.

Here’s where it gets gory. Researchers found that anatomists rarely cut the top of the skull to examine the brains inside, explains study author Piers Mitchell. Out of the 54 skulls he and his doctoral student Jenna Dittmar, lead author on the paper, examined, only one was sliced in half. Though there were few tool marks on the crania, the authors note that their positioning indicates that the cadavers were likely dissected rather than undergoing an autopsy. And many of the skulls lacked any marks, leading them to believe that the flesh was removed through boiling in order to preserve the crania.

Adults, on the other hand, were sliced and diced every which way. “Often an adult would be dissected and chopped into lots of small pieces,” says Mitchell. “The top of their head would be removed and so on to look at the brain. And then when everyone had finished studying it, then they would be reburied.”

The obvious care taken in the infant and fetus dissections supports the pivotal role these infants played in the study of early anatomy. Many were likely preserved and used as teaching aids for multiple generations of students, the authors note. The comparatively pristine condition of these specimens was also likely the reason that researchers didn’t realize that these were dissection subjects until now.

These 54 skulls are representatives of the long line of infants and fetuses that anatomists studied to better understand both the conditions that caused their deaths, as well as the general stages of human development. “They started to understand the embryological organism as something that was the beginnings of us: us as people, us as human beings,” says Morgan, who wasn’t involved in the recent study.

The idea of giving your baby’s body up for dissection might shock many today. But in Victorian England, things were different. In the 1800s, mothers didn’t necessarily consider their fetuses and infants as members of society like many do now, explains Morgan. Before the advent of the ultrasound, mothers and anatomists of this time understood very little about gestation of the budding person.

Times were also tough. “This was a time of Charles Dickens and Scrooge,” says Mitchell. In an era of poverty and disease, there were few guarantees that the developing fetus would survive, and women regularly miscarried. Because of this, parents often didn’t form attachments to their newborn infants or fetuses, and willingly handing over their remains to anatomists if they were claimed by death.

For some, a miscarriage could even be a relief. There were few available forms of birth control in the 1800s in Great Britain. “Women [were] becoming pregnant in a world where they really don't have much in the way of controlling how many pregnancies they have or when they happen,” says Shannon Withycombe, medical historian at the University of New Mexico who was not involved with the research. There was also an intense stigma attached to being a single mother. So some mothers resorted to infanticide, selling the cadavers to anatomists for dissection.

Those bodies were a boon for researchers, because it was increasingly hard to get their hands on adult bodies to study.

In Great Britain, the Murder Act of 1752 established the only legal source of bodies: the gallows. But executions couldn’t keep pace with the increasing needs of anatomy researchers. Demand for bodies ballooned: In 1828, over 800 students at the Schools of Anatomy in London dissected 450 to 500 bodies per year, yet at that time an average of 77 people were executed in the country per year.

To make up the difference, black market cadaver sales flourished. Resurrectionists, also known as body snatchers, pulled bodies from the grave and sold them for large sums by the inch. But the idea of disturbing the dead was appalling to many of the times, even causing riots. So in 1832, the Anatomy Act was passed to quell the black market body trade and regulate the supply of cadavers.

Though this law was not a cure-all, it did establish legal channels of fetus and infant remains for research. Studying these bodies helped anatomists learn about how these beings grow and change from the moment the sperm nestles into the egg. They also learned why so many miscarriages and infant deaths occurred, reducing the mortality rates.

“That, in turn, has allowed us to put an increased value on fetal life and infant life that wasn’t possible 100 years ago,” says Morgan.

The advent of the ultrasound in the mid 20th century gave this ideological shift some extra oomph. Parents could now see and personify their unborn children: they learned the sex, they named them. But it was these early dissections that gave anatomists their first glimpse into the otherwise hidden world of the developing baby.

By reducing the number of deaths and molding modern conceptions of fetus as child, fetus dissections ironically built the foundation for the modern stigmas against fetus dissection that we take for granted today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)