How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Dinosaurian Oddities

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/31/4e319094-d07c-4670-9ca1-e6a4081efbd1/allosaurus-camptosaurus-large.jpg)

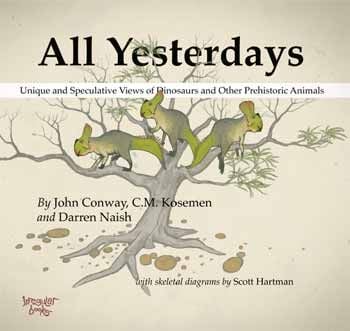

The dinosaurs I grew up with were both intensely exciting and incredibly dull. They were creatures unlike anything I had ever seen, but their drab, scaly flesh was always fit snugly to their bones with little embellishment. For decades, this has been the paradox of prehistoric restorations. Reconstructed skeletons are gloriously magnificent and introduce us to strange creatures that we never could imagined if we did not already know they existed. Yet the art of reviving these organisms has often been incredibly conservative. Dinosaurs, in particular, have often been “shrink-wrapped”–their skin tightly pulled around a minimalist layer of muscle distributed over the skeleton. This may be part of why dinosaur restorations look so weird. As John Conway, C.M. Kosemen, Darren Naish and Scott Harman argue in their new book All Yesterdays, no living lizard, fish, bird or mammal adheres to such a limited “skin on the bones” fashion. Dinosaurs were not only skeletally distinctive, but they undoubtedly looked stranger and behaved more bizarrely than we have ever imagined. The recently-published Dinosaur Art started to realize these possibilities, but All Yesterdays goes even further in melding science and speculation about dinosaur biology.

On a superficial level, All Yesterdays is a gorgeous collection of speculative artwork. Divided into two sections–the first featuring Mesozoic life in new or little-seen vignettes, and the second imagining how we would restore modern animals if we only had partial skeletons to work from–the book features some of the most wonderful paleoart I’ve ever seen. Scott Hartman’s crisp skeletal reconstructions form the framework from which Conway and Kosemen play with muscle, fat and flesh, and, following Naish’s introductory comments, Kosemen provides scientific commentary about how each illustration is not quite so outlandish as it seems. A curious Camptosaurus approaching an Allosaurus at rest is a reminder that, much like modern animals, prey and predators were not constantly grappling with each other, just as a snoozing rendition of the Tyrannosaurus “Stan” shows that even the scariest dinosaurs had to snooze. The gallery’s feathered dinosaurs are especially effective at demonstrating the fluffy weirdness of the Mesozoic. Conway’s peaceful scene of feather draped Therizinosaurus browsing in a tree grove is the best rendition of the giant herbivore I’ve ever seen, and his fluffy, snowbound Leaellynasaura are unabashedly adorable.

The second half of the book continues the same theme, but in reverse. How would artists draw a cat, an elephant or a baboon if we only had skeletons or bone fragments? And what would those scraps suggest about the biology of long-lost animals? If there are paleontologists in the future, and they have no other source of information about our world, how will they restore the animals alive today? They might have no knowledge of the fur, fat, feathers and other structures that flesh out modern species, creating demonic visions of reptilian cats, eel-like whales and vampire hummingbirds.

Working in concert, the two sections will give casual readers and paleoartists a jolt. While some might gripe about Todd Marshall adding too many spikes and dewlaps to his dinosaurs, or Luis Rey envisioning deinonychosaurs at play, the fact of the matter is that dinosaurs probably had an array of soft tissue structures that made them look far stranger than the toned-down restorations we’re used to. As All Yesterdays presents in various scenes, maybe sauropods liked to play in the mud, perhaps hadrosaurs were chubbier than we ever imagined and, as depicted in one nightmare-inducing panel, Stegosaurus could have had monstrous genitals. None of these scenarios are supported by direct evidence, but they are all within the realm of possibility.

More than a gallery of speculative art, All Yesterdays is an essential, inspirational guide to any aspiring paleoartist. Those who restore prehistoric life are limited by the evidence at hand, this is true, but “more conservative” does not mean “more accurate.” Using comparisons with modern animals, artists have far more leeway than they have ever exercised in imagining what prehistoric life was like. We’ve seen enough Deinonychus packs tearing apart Tenontosaurus, and far too many malnourished dinosaurs. We need more fat, feathers, accessory adornments and scenes from quieter moments in dinosaur lives that do not involve blood and spilled viscera. Professional paleoartists are beginning to embrace these ideas–Jason Brougham’s recent restoration of Microraptor is an appropriately fluffy, bird-like animal rather than the flying monster Naish and collaborators decry–but All Yesterdays is a concentrated dose of prehistoric possibilities that are being artistically explored.

Some of the book’s restorations may turn out to look quite silly. As lovely as Conway’s rendition is, I still don’t buy the “bison-back” idea for high-spined dinosaurs such as Ouranosaurus. Then again, depending on what we discover in the future, some of the illustrations might seem quite prescient. The important thing is that All Yesterdays demonstrates how to push the boundaries of what we imagine while still drawing on scientific evidence. The book is a rare treat in that each section explicitly lays the inspiration for each speculative vision, providing references for those who want to dig deeper.

If anything, All Yesterdays shows that we should not be afraid of imagination in science. Even though we know far more about dinosaur biology and anatomy than ever before, there are still substantial gaps in our understanding. In these places, where bones might not have much to tell us, science meets speculation. The result is not anything-goes garishness, but an exploration of possibilities. Somewhere within that murky range of alternatives, we may start to approach what dinosaurs were truly like.

You can purchase All Yesterdays in any of its various formats here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)