Clad in a white lab-coat, 26-year-old bespectacled microbiologist Balaram Khamari hunches over dozens of petri dishes, each filled with invisible colonies of bacteria. Two days before, Balaram filled a few of these petri dishes with agar—a jelly-like substance isolated from seaweed. A day after that, he streaked bacteria on the agar and slid the petri dishes into an incubator. Balaram was waiting for the bacteria to feed on the agar and multiply into colorful patterns, but not in the name of science; the microbiologist crafted the samples in the petri dishes to become works of art.

A doctoral research scholar in the biosciences department at India’s Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning, Puttaparthi, Balaram is part of a growing tribe of researchers around the world who use microorganisms to create stunning pictures. The practice, known as agar art, involves scientists culturing microbes on the jelly-like growth medium. “Microbial art allows me to pursue my love for creative arts as well as fascination for science at one place,” Balaram says.

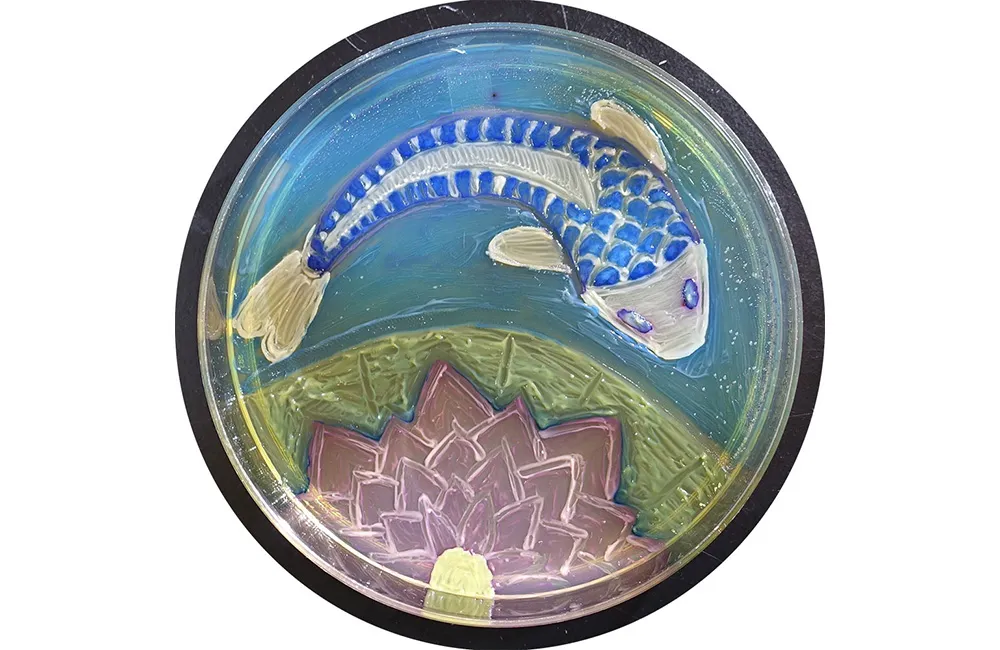

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/8a/b38ac6fe-97a7-4eb3-bd53-739bb2e90eeb/2_agar-art-2020-traditional-general-3rd-place_web2.jpg)

Scientists began to use agar for experiments as a way to see how microorganisms—which were previously grown on solid food—developed. Agar powder is mixed with sterilized water and nutrients in a petri dish to create a transparent, semi-solid substance. Scientists incorporate microorganisms, like fungi and bacteria, to the mixture and watch them develop in the gel under a microscope.

Despite its growing popularity over the past five years, microbial art isn't a recent fad. Alexander Fleming, who discovered the antibiotic properties of penicillin on an agar plate in 1928, created images using live organisms. Yet, this genre of scientific art didn’t gather much attention from researchers until the last decade, when the American Society of Microbiology brought agar art into the spotlight in 2015 with an annual contest.

In 2020, Balaram’s work of India's national bird, “Microbial Peacock,” won second prize in the traditional category—which features creations made with live organisms.

Balaram needed four attempts over two weeks to get the growth of the various organisms just right. "I used Escherichia Coli (E.coli) for the body of the peacock while arranging both E.coli and Staphylococcus aureus [the two most commonly encountered human pathogens] alternately for the individual tail feathers," he says. "The small colonies around the head of the peacock and the eyeball were home to Enterococcus faecalis, a gut bacterium that produces tiny and distinct colonies."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/52/9452bc72-4822-4ae6-91f3-c2581c3b7b2e/4_ablution_web2.jpg)

The scientists working in the artform have to be careful, as they sometimes use human pathogens— like Staphylococcus aureus, which can cause pneumonia and bone infections—for their designs. To avoid accidents in the lab, agar artists often work with microbes in a controlled environment. And scientists often have to wait days to see whether the microbial growth they started turns into an inspiring image. "Agar art is time consuming and the outcome isn't always as desired," says Balaram. "One needs to be extremely careful while inoculating the microbes on the agar plate.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/23/a3233e1f-207d-49be-ae1c-ed0f6eb7aafd/5_hungarian-folk-art_web2.jpg)

Frederik Hammes, a microbiologist at Eawag—a leading aquatic research institute in Zurich, Switzerland,—sometimes adds powdered charcoal to his agar to make the background black, a color he prefers. "I got the idea to paint on agar from seeing all the colorful colonies we isolated as part of a science fair demonstration in 2005," he says. "The first design I tried was Van Gogh's sunflowers, as his colors and broad style strokes suited with the working of bacteria on agar".

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/6a/546a730e-e23d-49d1-a3c3-88633a9c2388/dsc01421_web2.jpg)

Since that first design in a petri dish in 2005, Hammes has moved on to craft 3-D agar art—creations that rise up off the petri dish like sculptures. He gets some of his favorite microbes from a familiar place many people associate with a certain funk. “I have always isolated artistic bacteria from the soles of my feet,” says Hammes. “So, I suggest that an agar artist collects samples from different sources to eventually find that one spectacular organism.”

With many labs shut down during the pandemic, some researchers have started experimenting with available yeast and fungus at their homes. Hammes conducts workshops online to teach others the art. Many students post their creations to social media.

Balaram spends his weekends experimenting with various microbes, crafting a palette that will give him a better chance of winning first prize in this year’s event. “I am planning to submit a portrait-sketch for this year’s contest entry using E.coli,” says Balaram. “It imparts a pale yellow shade, which could be used perfectly to paint the skin.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/07/da076f5c-bb11-40c3-8ce4-057e749bf8f8/1_agar-art-2020-web-mobile.jpg)

:focal(594x308:595x309)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/e4/04e43bca-4304-4eef-9b8e-195a4a302944/1_agar-art-2020_web_social.jpg)