How a Misdrawn Map Put 1,400 Chimps and a Rare Plant in Peril

Miners and farmers are moving into a protected forest in Congo thanks in part to an administrative blooper

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/6e/666e5765-9ac5-4cba-a7ba-1583478fd41c/chimp.jpg)

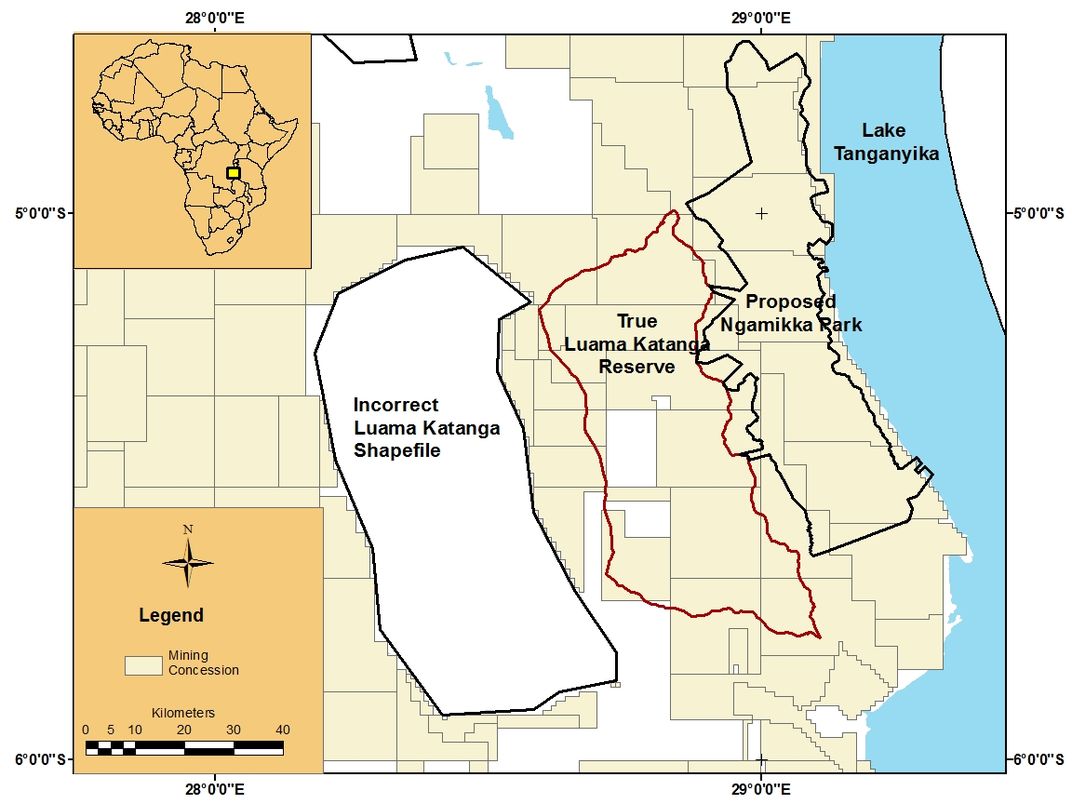

We all make mistakes, but this is one for the record books. Thanks to an administrative error, the recognized border of a protected region in Congo is now about 30 miles shy of the one the country actually established back in 1947. With that land seemingly all for the taking, cattle ranchers, farmers and miners are moving in, threatening both a newly discovered species of plant and around 1,400 chimpanzees.

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) recently discovered the error, which traces back to an incorrect map of the Luama Katanga Reserve. Sometime before 2011, the World Conservation Monitoring Centre in the U.K. acquired the coordinates of Luama Katanga for a GIS layer they were putting together to map all of the world’s protected areas. According to the WCS, however, whoever entered the data failed to double-check it. It seems like someone had haphazardly drawn a bubble on the map—perhaps a placeholder intended to be updated later—about 30 miles west of the actual reserve.

Luama Katanga, located on the shores of Lake Tanganika in southeastern Congo, is home to more than 900 species, including hundreds of chimpanzees. Additionally, WCS scientist Miguel Leal discovered a new species of fern-like plant in 2012, which was found clinging to a rocky wall near a small waterfall deep in the forest. He named it Dorstenia luamensis after the protected area.

Once the World Conservation Monitoring Centre released their map, the Congolese government used it to allocate mining concessions. The government’s original intention was to avoid conflicts with the park, but they did not know the map they were basing their decisions on was flawed. As a result, mining permits were granted within the actual reserve. From there, the park’s predicament only worsened. In 2011 Congo's environment minister removed official protected status from much of the wrongly mapped park and opened that area up for more mining, according to an email from the WCS.

The conservation group kept the mapping gaffe to itself for more than a year, and in the meantime started lobbying the country’s environment minister to reinstate the entire park with its original borders. So far things have been moving very slowly, according to Andrew Plumptre, director of WCS’s Albertine Rift Program. For now, conservationists have managed to gain protection for a small area that encompasses the place where Leal found D. luamensis. Miners have yet to reach that region, so it's still relatively pristine. On the other hand, the WCS points out that they have no idea if there’s any other valuable biodiversity there besides D. luamensis, which means the rest of the park's unique inhabitants, such as the endangered chimps, are still at risk.

Given the lack of progress, the organization decided to go public about the problem this week at the IUCN World Parks Congress in Sydney, a global conservation meeting that only occurs once every decade. “We wanted to highlight this issue to put pressure [on the government] to make this happen,” Plumptre wrote in an email. Regardless of whether mapping errors or ill-advised decisions by the government are to blame, salvaging the reserve may still be an uphill battle.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)