One frosty October morning, I climbed a winding mile-long path to the North Lookout at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Eastern Pennsylvania. Laurie Goodrich, the director of conservation science, was already on watch, staring down the ridge as a chilly wind swept in from the northwest. She has been scanning this horizon since 1984, and the view is as familiar to her as an old friend.

“Bird coming in, naked eye, slope of Five,” Goodrich said to her assistant, using a long-established nickname for a distant rise. A sharp-shinned hawk popped up from the valley below, racing by just above our heads. Another followed, then two more. A Cooper’s hawk swooped close, taking a swipe at the great horned-owl decoy perched on a wooden pole nearby. Goodrich seemed to be looking everywhere at once, calmly calling out numbers and species names as she greeted arriving visitors.

Like the hawks, the birdwatchers arrived alone or in pairs. Each found a spot in the rocks, placed thermoses and binoculars within easy reach, and settled in for the show, bundling up against the wind. By 10 a.m., more than two dozen birders were at the lookout, arrayed on the rocks like sports fans on bleachers. Suddenly they gasped—a peregrine falcon was barreling along the ridge toward the crowd.

By the end of the day, the lookout had been visited by several dozen birders and a flock of 60 chatty middle-schoolers. Goodrich and her two assistants—one from Switzerland, the other from the Republic of Georgia—had counted two red-shouldered hawks, four harriers, five peregrine falcons, eight kestrels, eight black vultures, ten merlins, 13 turkey vultures, 34 red-tailed hawks, 23 Cooper’s hawks, 39 bald eagles and 186 sharp-shinned hawks. It was a good day, but then again, she said, most days are.

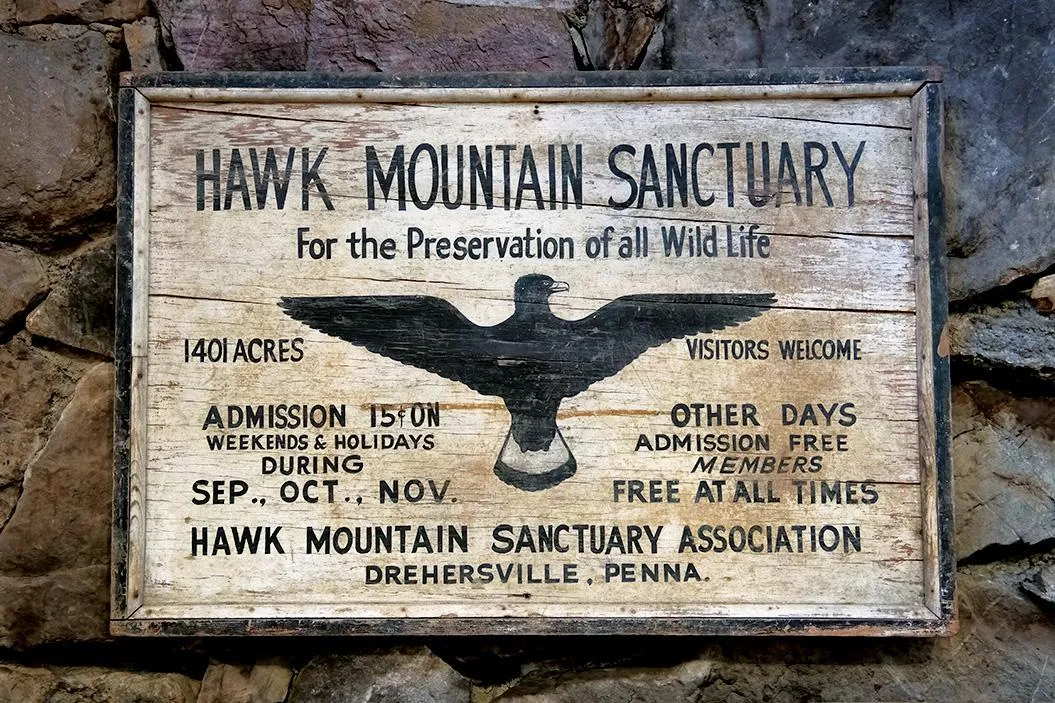

The abundance of raptors at North Lookout owes a great deal to topography and wind currents, both of which funnel birds toward the ridgeline. But it owes even more to an extraordinary activist named Rosalie Edge, a wealthy Manhattan suffragist who founded Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in 1934. Hawk Mountain, believed to be the world’s first refuge for birds of prey, is a testament to Edge’s passion for birds—and to her enthusiasm for challenging the conservation establishment. In the words of her biographer, Dyana Furmansky, Edge was “a citizen-scientist and militant political agitator the likes of which the conservation movement had never seen.” She was described by a contemporary as “the only honest, unselfish, indomitable hellcat in the history of conservation.”

* * *

Throughout history, birds have been hunted not only for meat, but for beauty. Aztec artisans decorated royal headdresses, robes and tapestries with intricate featherwork designs, sourcing their materials from elaborate aviaries and far-flung trading networks. Europe’s first feather craze was kicked off by Marie Antoinette in 1775, when the young queen started to decorate her towering powdered wig with immense feather headdresses. By the late 19th century, ready-to-wear fashions and mail-order firms made feathered finery available to women of lesser means in both Europe and North America. Hats were decorated with not only individual feathers but the stuffed remains of entire birds, complete with beaks, feet and glass eyes. The extent of the craze was documented by the ornithologist Frank Chapman in 1886. Out of 700 hats whose trimmings he observed on the streets of New York City, 542 were decorated with feathers from 40 different bird species, including bluebirds, pileated woodpeckers, kingfishers and robins. Supplying the trade took an enormous toll on birds: In that same year, an estimated five million North American birds were killed to adorn ladies’ hats.

Male conservationists on both sides of the Atlantic tended to blame the consumers—women. Other observers looked deeper, notably Virginia Woolf, who in a 1920 letter to the feminist periodical the Woman’s Leader spared no sympathy for “Lady So-and-So” and her desire for “a lemon-coloured egret...to complete her toilet,” but also pointed directly at the perpetrators: “The birds are killed by men, starved by men, and tortured by men—not vicariously, but with their own hands.”

In 1896, Harriet Hemenway, a wealthy Bostonian from a family of abolitionists, hosted a series of strategic tea parties along with her cousin Minna Hall, during which they persuaded women to boycott feathered fashions. The two women also enlisted businessmen and ornithologists to help revive the bird-protection movement named after wildlife artist John James Audubon, which had stalled shortly after its founding a decade earlier. The group’s wealth and influence sustained the Audubon movement through its second infancy.

Hemenway and her allies successfully pushed for state laws restricting the feather trade, and they championed the federal Lacey Act, passed in 1900, which banned the interstate sale and transport of animals taken in violation of state laws. Activists celebrated in 1918 when Congress effectively ended the plume trade in the United States by passing the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Over the following years, bird populations recovered. In Florida in the 1920s, participants in the national Christmas bird count—an Audubon tradition inaugurated by Chapman in 1900—reported total numbers of great egrets in the single digits. By 1938, one birdwatcher in southwestern Florida counted more than 100 great egrets in a single day.

The end of the plume trade was an enormous conservation success, but over the next decade, as the conservation movement matured, its leaders became more complacent and less ambitious. On the brink of the Great Depression, Rosalie Edge would start to disturb their peace.

Edge was born in 1877 into a prominent Manhattan family that claimed Charles Dickens as a relation. As a child, she was given a silk bonnet wreathed with exquisitely preserved ruby-throated hummingbirds. But until her early 40s, she took little interest in living birds, instead championing the cause of women’s suffrage. In late 1917, New York became the first state in the eastern United States to guarantee women the right to vote, opening the door to the establishment of nationwide women’s suffrage in 1920. Edge then turned her attention to taming Parsonage Point, a four-acre property on Long Island Sound that her husband, Charlie, had purchased in 1915.

During World War I, with house construction delayed by shortages, Edge and her family lived on the property in tents. Every morning, she crept out to watch a family of kingfishers, and soon became acquainted with the local quail, kestrels, bluebirds and herons. While her children Peter and Margaret, then 6 and 4, planted pansies in the garden, Edge decorated the trees and shrubs with suet and scattered birdseed on the ground.

Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction

A vibrant history of the modern conservation movement―told through the lives and ideas of the people who built it.

In spite of their joint endeavors at Parsonage Point, Edge and her husband drifted apart. After an argument one evening in the spring of 1921, Rosalie left with the two children for her brownstone on the Upper East Side. The Edges did not divorce, but they eventually secured a legal separation, which both avoided the scandal of a public divorce and required Charlie to support Rosalie with a monthly allowance—which he reliably did. For Rosalie, however, the split was devastating. She mourned not only the loss of her husband, but the loss of her home at Parsonage Point—“the air, the sky, the gulls flying high.”

For more than a year, Edge took little notice of the birds around her. But in late 1922, she began to make notes on the species she saw in the city. Three years later, on a May evening, she was sitting by an open window when she noticed the staccato shriek of a nighthawk. Years later, she would muse that birdwatching “comes perhaps as a solace in sorrow and loneliness, or gives peace to some soul wracked with pain.”

Edge began birding in nearby Central Park, often with her children and red chow chow in tow. She soon learned that the park was at least as rich in bird life as Parsonage Point, with some 200 species recorded there every year. At first, Edge’s noisy entourage and naive enthusiasm irritated the park’s rather shy and clannish community of bird enthusiasts. She was a quick learner, however, and she began checking the notes that Ludlow Griscom, then the American Museum of Natural History’s associate curator of birds, left for other birders in a hollow tree each morning. Soon, she befriended the man himself. Her son, Peter, shared her renewed passion for birdwatching, and, as she grew more knowledgeable, she would call his school during the day with instructions about what to look for during his walk home. (When the school refused to pass on any more phone messages, she sent a telegram.)

Edge gained the respect of park birders, and in the summer of 1929, one of them mailed her a pamphlet called “A Crisis in Conservation.” She received it at a Paris hotel where she was ending a European tour with her children. “Let us face facts now rather than annihilation of many of our native birds later,” the authors had written, arguing that bird protection organizations had been captured by gun and ammunition makers, and were failing to guard the bald eagle and other species that hunters targeted.

“I paced up and down, heedless that my family was waiting to go to dinner,” Edge later recalled. “For what to me were dinner and the boulevards of Paris when my mind was filled with the tragedy of beautiful birds, disappearing through the neglect and indifference of those who had at their disposal wealth beyond avarice with which these creatures might be saved?”

When Edge returned to Manhattan, her birding friends suggested she contact one of the authors, Willard Van Name, a zoologist at the American Museum of Natural History. When they met for a walk in Central Park, Edge was impressed by his knowledge of birds and his dedication to conservation. Van Name, who had grown up in a family of Yale scholars, was a lifelong bachelor and confirmed misanthrope, preferring the company of trees and birds to that of people. He confirmed the claims he had made in “A Crisis in Conservation,” and Edge, appalled, resolved to act.

* * *

On the morning of October 29, 1929, Edge walked across Central Park to the American Museum of Natural History, noting the birds she saw along the way. When she entered the small ground-floor room where the National Association of Audubon Societies was conducting its 25th annual meeting, the assembly stirred with curiosity. Edge was a life member of the association, but annual meetings tended to be familial gatherings of directors and employees.

Edge listened as a member of the board of directors finished a speech extolling the association, which represented more than a hundred local societies. It was the leading conservation organization in North America—if not the world—during a time of intense public interest in wildlife in general and birds in particular. Its directors were widely respected scientists and successful businessmen. As the board member concluded his remarks, he mentioned that the association had “dignifiedly stepped aside” from responding to “A Crisis in Conservation.”

Edge raised her hand and stood to speak. “What answer can a loyal member of the society make to this pamphlet?” she asked. “What are the answers?”

At the time, Edge was almost 52 years old. Slightly taller than average, with a stoop that she would later blame on hours of letter-writing, she favored black satin dresses and fashionably complicated (though never feathered) hats. She wore her graying hair in a simple knot at the back of her head. She was well-spoken, with a plummy, cultivated accent and a habit of drawing out phrases for emphasis. Her pale blue eyes took in her surroundings, and her characteristic attitude was one of imperious vigilance—as a New Yorker writer once put it, “somewhere between that of Queen Mary and a suspicious pointer.”

Edge’s questions were polite but piercing. Was the association tacitly supporting bounties on bald eagles in Alaska, as the pamphlet stated? Had it endorsed a bill that would have allowed wildlife refuges to be turned into public shooting grounds? Her inquiries, as she recalled years later, were met with leaden silence—and then, suddenly, outrage.

Frank Chapman, the museum’s bird curator and the founding editor of Bird-Lore, the Audubon association magazine, rose from the audience to furiously condemn the pamphlet, its authors and Edge’s impertinence. Several more Audubon directors and supporters stood to berate the pamphlet and its authors. Edge persevered through the clamor. “I fear I stood up very often,” she recalled with unconvincing remorse.

When Edge finally stopped, association president T. Gilbert Pearson informed her that her questions had taken up the time allotted to the showing of a new moving picture, and that lunch was getting cold. Edge joined the meeting attendees for a photograph on the museum’s front steps, where she managed to pose among the directors.

By the end of the day, Edge and the Audubon directors—along with the rest of the country—would learn that stock values had fallen by billions of dollars, and families rich and poor were ruined. The day would soon be known as Black Tuesday.

As the country entered the Great Depression, and Pearson and the Audubon association showed no interest in reform, Edge joined forces with Van Name, and the two of them spent many evenings in the library of her brownstone. The prickly scientist became such a fixture in the household that he began to help her daughter, Margaret, with her algebra homework. Edge named their new partnership the Emergency Conservation Committee.

The committee’s colorfully written pamphlets placed blame and named names. Requests for additional copies poured in, and Edge and Van Name mailed them out by the hundreds. When the Audubon leaders denied Edge access to the association’s list of members, she took them to court and prevailed. In 1934, faced with a declining and restive membership, Pearson resigned. In 1940, the association renamed itself the National Audubon Society and distanced itself from supporters of predator control, instead embracing protection for all bird species, including birds of prey. “The National Audubon Society recovered its virginity,” longtime Emergency Conservation Committee member Irving Brant wryly recalled in his memoir. Today, while the nearly 500 local Audubon chapters coordinate with and receive financial support from the National Audubon Society, the chapters are legally independent organizations, and they retain a grassroots feistiness recalling that of Edge.

The Emergency Conservation Committee would last for 32 years, through the Great Depression, the Second World War, five presidential administrations and frequent quarrels between Edge and Van Name. (It was Van Name who referred to his collaborator as an “indominable hellcat.”) The committee published dozens of pamphlets and was instrumental in not only reforming the Audubon movement but establishing Olympic and Kings Canyon national parks and increasing public support for conservation in general. Brant, who later became a confidant of Harold Ickes, Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of the interior, remembered that Ickes would occasionally say of a new initiative, “Won’t you ask Mrs. Edge to put out something on this?”

* * *

“What is this love of birds? What is it all about?” Edge once wrote. “Would that the psychologists might tell us.”

In 1933, Edge’s avian affections collided with a violent Pennsylvania tradition: On weekends, recreational hunters gathered on ridgetops to shoot thousands of birds of prey, for sport as well as to reduce what was believed to be rampant hawk predation on chickens and game birds. Edge was horrified by a photo showing more than 200 hawk carcasses from the area lined up on the forest floor. When she learned that the ridgetop and its surrounding land was for sale, she was determined to buy it.

In the summer of 1934, she signed a two-year lease on the property—Van Name loaned her the $500—reserving an option to purchase it for about $3,500, which she did after raising funds from supporters. Once again she clashed with the Audubon association, which had also wanted to buy the land.

Edge, contemplating her new real estate, knew that fences and signs would not be enough to stop the hunters; she would have to hire a warden. “It is a job that needs some courage,” she cautioned when she offered the position to a young Boston naturalist named Maurice Broun. Wardens charged with keeping plume hunters out of Audubon refuges faced frequent threats and harassment, and had been murdered by poachers in 1905. Though Broun was newly married, he was not dissuaded, and he and his wife, Irma, soon moved to Pennsylvania. At Edge’s suggestion, Broun began to make daily counts of the birds that passed over the mountain each fall. He usually counted hawks from North Lookout, a pile of sharp-edged granite on the rounded peak of Hawk Mountain.

In 1940, even T. Gilbert Pearson—the Audubon president emeritus who had scolded Edge at the 1929 meeting—paid a visit. After passing time with the Brouns and noting the enthusiasm of visiting students, he wrote a letter to Edge. “I was impressed with the great usefulness of your undertaking,” he wrote. “You certainly are to be commended for carrying through to success this laudable dream of yours.” He enclosed a check for $2—the sanctuary membership fee at the time—and asked to be enrolled as a member.

* * *

Over the decades, Hawk Mountain and its raptor-migration data would assume a growing—if mostly unheralded—role in the conservation movement. Rachel Carson first visited Hawk Mountain in the fall of 1945. The raptors, she noted with delight, “came by like brown leaves drifting on the wind.” She was then 38 and serving as a writer and editor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Sometimes a lone bird rode the air currents,” she wrote, “sometimes several at a time, sweeping upward until they were only specks against the clouds or dropping down again toward the valley floor below us; sometimes a great burst of them milling and tossing, like the flurry of leaves when a sudden gust of wind shakes loose a new batch from the forest trees.”

Fifteen years later, when Carson was studying the effects of widespread pesticide usage, she sent a letter to the sanctuary caretaker: “I have seen you quoted at various times to the effect that you now see very few immature eagles in fall migration over Hawk Mountain. Would you be good enough to write me your comments on this, with any details and figures you think significant?”

Broun responded that between 1935 and 1939, the first four years of the daily bird counts at Hawk Mountain, some 40 percent of the bald eagles he observed were young birds. Two decades later, however, young birds made up just 20 percent of the total number of bald eagles recorded, and in 1957, he had counted only one young eagle for every 32 adults. Broun’s report would become a key piece of evidence in Carson’s legendary 1962 book Silent Spring, which exposed the environmental damage done by widespread use of the pesticide DDT.

In the years since Maurice Broun began his daily raptor count from North Lookout, Hawk Mountain has accumulated the longest and most complete record of raptor migration in the world. From these data, researchers know that golden eagles are more numerous along the flyway than they used to be, and that sharp-shinned hawks and red-tailed hawks are less frequent passersby. They also know that kestrels, the smallest falcons in North America, are in steep decline—for reasons that remain unclear, but researchers are launching a new study to identify the causes.

And Hawk Mountain is no longer the only window on raptor migration; there are some 200 active raptor count sites in North and South America, Europe and Asia, some founded by the international students who train at Hawk Mountain every year. Taken together, these lengthening data sets can reveal larger long-term patterns: While red-tailed hawks are less frequently seen at Hawk Mountain, for example, they are now more frequently reported at sites farther north, suggesting that the species is responding to warmer winters by changing its migration strategy. In November 2020, Hawk Mountain Sanctuary scientist J.F. Therrien contributed to a report showing that golden eagles are returning to their Arctic summering grounds progressively earlier in the year. While none of the raptors that frequent the sanctuary are currently endangered, it’s important to understand how these species are responding to climate change and other human-caused disruptions.

“The birds and animals must be protected,” Edge once wrote, “not merely because this species or another is interesting to some group of biologists, but because each is a link in a living chain that leads back to the mother of every living thing on land, the living soil.”

Edge didn’t live to see this expansion of Hawk Mountain’s influence. But by the end of her life, she was widely recognized as one of the most important figures in the American conservation movement. In late 1962, less than three weeks before her death, Edge attended one last Audubon gathering, showing up more or less unannounced at the annual meeting of the National Audubon Society in Corpus Christi, Texas. Edge was 85 and physically frail. With some trepidation, president Carl Bucheister invited his society’s former adversary to sit on the dais with him during the banquet. When Bucheister led her to her seat and announced her name, the audience—1,200 bird lovers strong—gave her a standing ovation.

Adapted from Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction, by Michelle Nijhuis. Copyright 2021 Michelle Nijhuis. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5c/0d/5c0d3920-b20e-4b2f-b46a-154cf944d722/mobileopener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/d1/10d17f25-c502-4f27-9cf9-221b75730bf5/untitled-2.jpg)