How Plastic Pollution Can Carry Flame Retardants Into Your Sushi

Research shows that plastic particles can absorb pollution from water, get eaten by fish and carry the toxins up the food chain

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131121081139sushi-copy.jpg)

In 2009, a pair of research vessels embarked from California to study an area of the Pacific Ocean known as the Great Pacific garbage patch. What they found was disconcerting.

Over the course of 1700 miles, they sampled the water for small pieces of plastic more than 100 times. Every single time, they found a high concentration of tiny plastic particles. “It doesn’t look like a garbage dump. It looks like beautiful ocean,” Miriam Goldstein, the chief scientist of the vessel sent by Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said afterward. “But then when you put the nets in the water, you see all the little pieces.”

In the years since, a lot of public attention has been justifiably paid to the physical effects of this debris on animals’ bodies. Nearly all of the dead albatrosses sampled on Midway island, for instance, were found to have stomachs filled with plastic objects that likely killed them.

But surprisingly little attention has been paid to the more insidious chemical consequences of this plastic on food webs—including our own. “We’d look over the bow of the boat and try to count how many visible pieces of plastic were there, but eventually, we got to the point that there were so many pieces that we simply couldn’t count them,” says Chelsea Rochman, who was aboard the expedition’s Scripps vessel and is now a PhD student at San Diego State University. “And one time, I was standing there and thinking about how they’re small enough that many organisms can eat them, and the toxins in them, and at that point I suddenly got goosebumps and had to sit down.”

“This problem is completely different from how it’s portrayed,” she remembers thinking. “And, from my perspective, potentially much worse.”

In the years since, Rochman has shown how plastics can absorb dangerous water-borne toxins, such as industrial byproducts like PCB (a coolant) and PBDE (a flame retardant). Consequently, even plastics that contain no toxic substances themselves, such as polyethylene—the most widely used plastic, found in packaging and tons of other products—can serve as a medium for poisons to coalesce from the marine environment.

But what happens to these toxin-saturated plastics when they’re eaten by small fish? In a study published today in Scientific Reports, Rochman and colleagues fill in the picture, showing that the toxins readily transfer to small fish through plastics they ingest and cause liver stress.This is an unsettling development, given that we already know such pollutants concentrate further the more you move up the food chain, from these fish to the larger predatory fish that we eat on a regular basis.

In the study, researchers soaked small pellets of polyethylene in the waters of San Diego Bay for three months, then tested them and discovered that they’d absorbed toxins leached into the water from nearby industrial and military activities. Next, they put the pollution-soaked pellets in tanks (at concentrations lower than those found in the Great Pacific garbage patch) with a small, roughly one-inch-long species called Japanese rice fish. As a control, they also exposed some of the fish to virgin plastic pellets that hadn’t marinated in the Bay, and a third group of fish got no plastic in their tanks at all.

Researchers still aren’t sure why, but many small fish species will eat these sort of small plastic particles—perhaps because, when covered in bacteria, they resemble food, or perhaps because the fish simply aren’t very selective about what they put in their mouths. In either case, over the course of two months, the fish in the experiment consumed many plastic particles, and their health suffered as a result.

“We saw significantly greater concentrations of many toxic chemicals in the fish that were fed the plastic that had been in the ocean, compared to the fish that got either clean plastic or no plastic at all,” Rochman says. “So, is plastic a vector for these chemicals to transfer to fish or to our food chain? We’re now fairly confident that the answer is yes.”

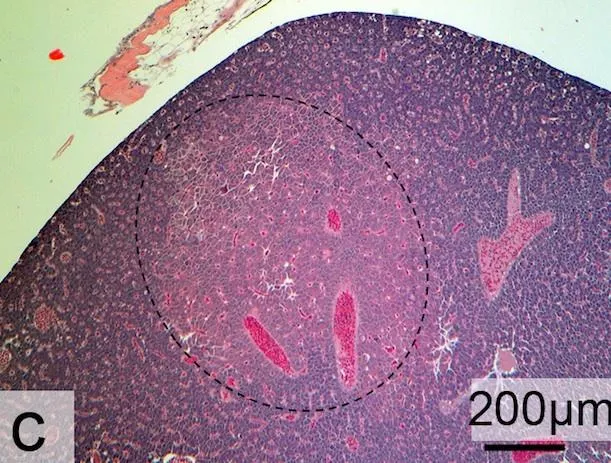

These chemicals, of course, directly affected the fishes’ health. When the researchers examined the tiny creatures’ livers (which filter out toxins in the blood) they found that the animals exposed to the San Diego Bay-soaked plastic had significantly more indications of physiological stress: 74 percent showed severe depletion of glycogen, an energy store (compared to 46 percent of fish who’d eaten virgin plastic and zero percent of those not exposed to plastic), and 11 percent exhibited widespread death of individual liver cells. By contrast, the fish in the other treatments showed no widespread death of liver cells. One particular plastic-fed fish had even developed a liver tumor during the experimental period.

All this is bad news for the entire food webs that rest upon these small fish, which include us. “If these small fish are eating the plastic directly and getting exposed to these chemicals, and then a bigger fish comes up and eat five of them, they’re getting five times the dose, and then the next fish—say, a tuna—eats five of those and they have twenty-five times the dose,” Rochman explains. “This is called biomagnification, and it’s very well-known and well-understood.”

This is the same reason why the EPA advises people to limit their consumption of large predatory fish like tuna. Plastic pollution, whether found in high concentrations in the Great Pacific garbage patch or in the waters surrounding any coastal city, appears to be central to the problem, serving as a vehicle that carries toxins into the food chain in the first place.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)