How Stress Hormones Impact the Behavior of Investors

Cortisol, a natural hormone, has been found to rise during times of market volatility and make people more risk-averse

:focal(2484x1361:2485x1362)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/e3/3be34b7d-c6a7-495e-963a-80b60f18b3d1/stock_market.jpg)

Imagine you're a stock trader playing the market. As you watch, it becomes extremely volatile, with prices swinging wildly from minute to minute. You have the opportunity to buy deeply undervalued assets or sell overvalued ones, with the potential of generating huge profits. But with such volatility, any decision to buy or sell brings the substantial risk of prices swinging in the opposite direction from what you'd hoped, making you look stupid (and lose tons of money) a few moments later.

So what do you do? Your behavior—in terms of taking on or avoiding risk—has long been considered a matter of personal preference. But a series of lab experiments, described in a paper published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicates that stock traders' risk-taking behavior (or lack thereof) might be more powerfully affected by the stress hormone cortisol than previously thought.

"Any trader knows that their body is taken on roller-coaster ride by the markets," John Coates, a neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge who co-authored the study and was a former trader for Goldman Sachs, said in a press statement. "What we haven't known until this study was that these physiological changes—the sub-clinical levels of stress of which we are only dimly aware—are actually altering our ability to take risk."

He and colleagues conducted a controlled lab experiment that sought to replicate the conditions of trading in a risky market. They recruited 28 volunteers and gave them hydrocortisone capsules (the pharmaceutical form of the hormone cortisol) daily for eight days, tailoring the dosage to increase their levels of the stress hormone by an average of 69 percent by the end of the period, the same amount of increase that the researchers had previously observed in actual traders stressed by volatile London markets. They also included eight volunteers who were given placebo capsules.

High levels of cortisol—produced by the adrenal gland and generally secreted in response to stress as a "flight or fight" reaction—can trigger a range of psychological and physiological effects in the human body. It releases glucose into the blood and increases blood pressure, readying the body for immediate action, but has been found to interfere with longer-term activities, weakening the immune system, slowing wound healing and hindering long-term memory and learning.

The researchers' work with the cortisol-dosed participants suggest a previously unknown effect of the hormone—though one that also makes intuitive sense as an evolutionarily beneficial response to danger. The hormone, in this case, made the study volunteers especially aversive to taking on risk.

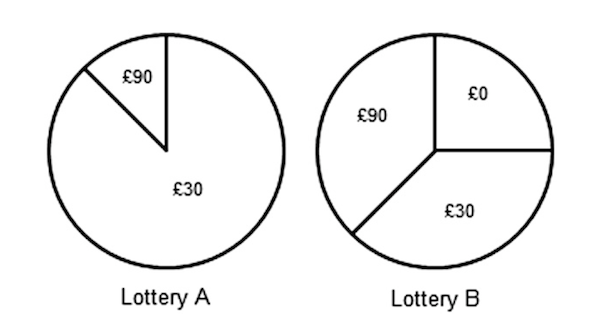

In the study, the participants were asked to choose between playing one of two lotteries that paid out real money. Option A, on the left, offered the certainty of a payout of at least 30 pounds, and a small chance at winning 90 pounds. Option B, on the right, offered the chance of winning no money at all, but a much greater chance of winning 90 pounds.

On the whole, the expected return (the value of each potential payout multiplied by the odds of actually getting it) is higher for option B, but it's also riskier, because the participant might get nothing. Other experiments have established that most people will choose option A, unless the expected return of option B gets so high that it becomes irresistible. If option B included a payout of a million pounds, for instance, it's easy to imagine that you might pick it despite the risk—but as long as the payouts are relatively similar, people like to choose the risk-free option. The point at which you'd switch from option A to option B indicates how risk-averse you are.

The researchers found that after people were dosed with cortisol for one day, they were slightly more risk-averse than the control group, requiring mildly higher disparities in expected return to push them over to the risky option. But they became dramatically more risk-averse over time: After eight days of taking the hydrocortisone, they chose risk-free lotteries nearly 80 percent of the time (as compared to 50 percent for the control group). On the whole, their risk premium (the amount of risk they were willing to put up with in exchange for the chance of a higher payout) fell by 44 percent.

Additionally, within the experimental group, increases in blood cortisol levels (as measured by blood and saliva tests) varied slightly—the researchers sought to cause everyone's levels to increase by 69 percent (the same as the real-life traders'), but there was some variation. Tellingly, those that had levels of the stress hormone increase the most grew most risk-averse.

The most interesting aspect of all this is that the researchers sought to replicate the blood cortisol trends they observed in real London stock traders, stressed by a volatile market: chronically rising over the course of a week or so, rather than spiking for a day and settling back down. The participants' risk-averse behaviors didn't show up until cortisol levels had similarly grown over time.

Admittedly, it's a small sample size, but if real-world traders behave anything like the study participants, the researchers argue, then cortisol could be acting as substantial (and underappreciated) factor in the behavior of traders, making them especially risk-averse when volatile, stressful markets persist for a week-long duration. During especially long-term periods of volatility—Coates points to the 2007-2009 financial crisis, when volatility in U.S. assets went from 12 percent to over 70 percent—cortisol levels and risk-averse behavior might rise even more than demonstrated in the study. He claims that one of the factors that exacerbated the crisis was the fact that so many investors were unwilling to take on risk and buy distressed assets—a behavior that perhaps could be traced, in part, to cortisol.

This sort of biological analysis of market behavior, Coates says, is much needed—part of the reason he switched from trading derivatives to investigating the body chemistry behind investment decisions. "Traders, risk managers and central banks cannot hope to manage risk if they do not understand that the drivers of risk taking lurk deep in our bodies," he said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)