How Tuberculosis Shaped Victorian Fashion

The deadly disease—and later efforts to control it—influenced trends for decades

:focal(381x190:382x191)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/69/b869261f-a697-49ad-810a-7e551b5e9b77/1888_petersons_magazine_fashion_plate.jpg)

Marie Duplessis, French courtesan and Parisian celebrity, was a striking Victorian beauty. In her best-known portrait, by Édouard Viénot, her glossy black hair frames a beautiful, oval face with sparkling eyes and ivory skin. But Duplessis’ fame was short-lived. Like Violetta, the protagonist in Giuseppe Verdi’s opera La Traviata whose tale Duplessis inspired, Duplessis was afflicted with tuberculosis, which killed her in 1847 at the age of 23.

By the mid-1800s, tuberculosis had reached epidemic levels in Europe and the United States. The disease, now known to be infectious, attacks the lungs and damages other organs. Before the advent of antibiotics, its victims slowly wasted away, becoming pale and thin before finally dying of what was then known as consumption.

The Victorians romanticized the disease and the effects it caused in the gradual build to death. For decades, many beauty standards emulated or highlighted these effects. And as scientists gained greater understanding of the disease and how it was spread, the disease continued to keep its hold on fashion.

“Between 1780 and 1850, there is an increasing aestheticization of tuberculosis that becomes entwined with feminine beauty,” says Carolyn Day, an assistant professor of history at Furman University in South Carolina and author of the forthcoming book Consumptive Chic: A History of Fashion, Beauty and Disease, which explores how tuberculosis impacted early 19th century British fashion and perceptions of beauty.

During that time, consumption was thought to be caused by hereditary susceptibility and miasmas, or “bad airs,” in the environment. Among the upper class, one of the ways people judged a woman’s predisposition to tuberculosis was by her attractiveness, Days says. “That’s because tuberculosis enhances those things that are already established as beautiful in women,” she explains, such as the thinness and pale skin that result from weight loss and the lack of appetite caused by the disease.

The 1909 book Tuberculosis: A Treatise by American Authors on Its Etiology, Pathology, Frequency, Semeiology, Diagnosis, Prognosis, Prevention, and Treatment confirms this notion, with the authors noting: “A considerable number of patients have, and have had for years previous to their sickness, a delicate, transparent skin, as well as fine, silky hair.” Sparkling or dilated eyes, rosy cheeks and red lips were also common in tuberculosis patients—characteristics now known to be caused by frequent low-grade fever.

“We also begin to see elements in fashion that either highlight symptoms of the disease or physically emulate the illness,” Day says. The height of this so-called consumptive chic came in the mid-1800s, when fashionable pointed corsets showed off low, waifish waists and voluminous skirts further emphasized women’s narrow middles. Middle- and upper-class women also attempted to emulate the consumptive appearance by using makeup to lighten their skin, redden their lips and color their cheeks pink.

The second half of the 19th century ushered in a radically transformed understanding of tuberculosis when, in 1882, Robert Koch announced that he had discovered and isolated the bacteria that cause the disease. By then, germ theory had emerged. This is the idea that microscopic organisms, not miasmas, cause certain diseases. Koch’s discovery helped germ theory gain more legitimacy and convinced physicians and public health experts that tuberculosis was contagious.

Preventing the spread of tuberculosis became the impetus for some of the first large-scale American and European public health campaigns, many of which targeted women’s fashions. Doctors began to decry long, trailing skirts as culprits of disease. These skirts, physicians said, were responsible for sweeping up germs on the street and bringing disease into the home.

Consider the cartoon "The Trailing Skirt: Death Loves a Shining Mark," which appeared in Puck magazine in 1900: The illustration shows a maid shaking off clouds of germs from her lady’s skirt as angelic-looking children stand in the background. Behind the maid looms a skeleton holding a scythe, a symbol of death.

Corsets, too, came under attack, as they were believed to exacerbate tuberculosis by limiting the movement of the lungs and circulation of the blood. “Health corsets” made with elastic fabric were introduced as a way to alleviate pressure on the ribs caused by the heavily boned corsets of the Victorian era.

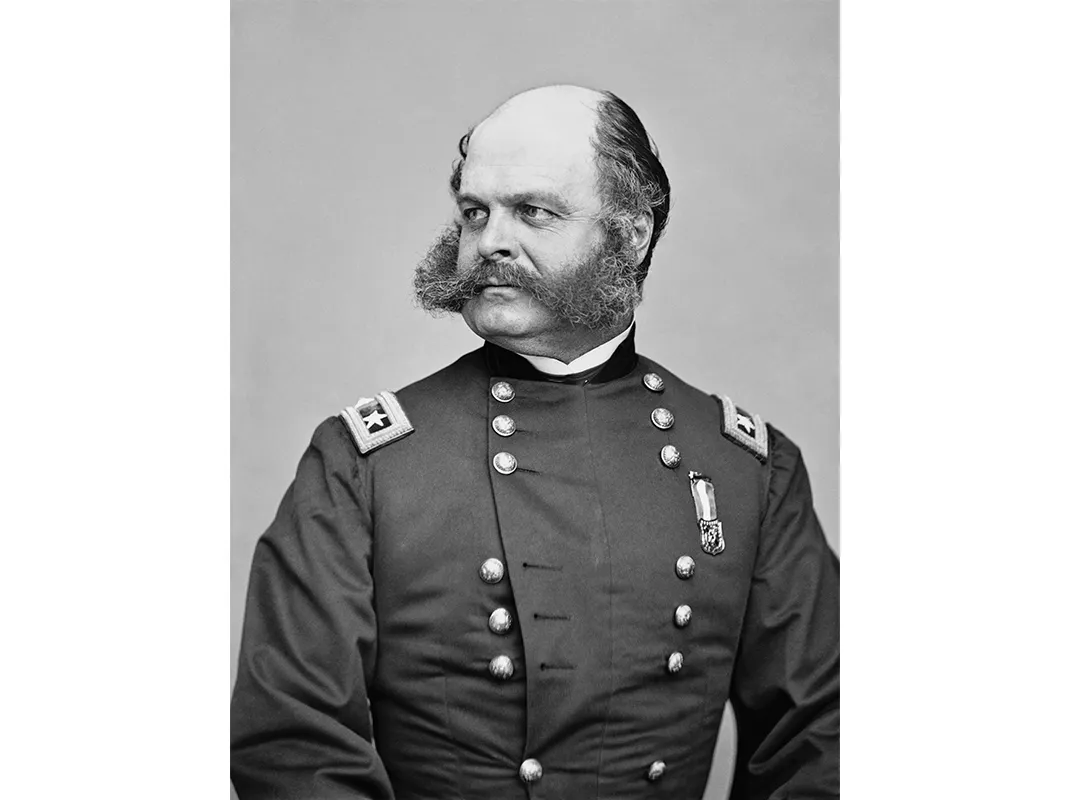

Men’s fashion was also targeted. In the Victorian period, luxuriant beards, sculpted mustaches and extravagant sideburns had been all the rage. The trend can be partly credited to British soldiers who grew facial hair to keep warm during the Crimean War in the 1850s. But facial hair was also popular in the United States where razors were difficult to use and often unsafe, especially when not cleaned properly. But by the 1900s, beards and mustaches themselves were deemed dangerous.

“There is no way of computing the number of bacteria and noxious germs that may lurk in the Amazonian jungles of a well-whiskered face, but their number must be legion,” Edwin F. Bowers, an American doctor known for pioneering reflexology, wrote in a 1916 issue of McClure’s Magazine. “Measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, tuberculosis, whooping cough, common and uncommon colds, and a host of other infectious diseases can be, and undoubtedly are, transmitted via the whisker route.”

By the time Bowers penned his spirited essay, facial hair had largely disappeared from the faces of American men, especially surgeons and physicians, who adopted the clean-shaven look to be more hygienic when caring for patients.

The Victorian ideal of looking consumptive hasn’t survived to the current century, but tuberculosis has had lingering effects on fashion and beauty trends. Once women’s hemlines rose a few inches at the beginning of the 1900s, for example, shoe styles became an increasingly important part of a woman’s overall look. And around the same time, doctors began prescribing sunbathing as a treatment for TB, giving rise to the modern phenomenon of tanning.