The Human Nose Can Distinguish Between One Trillion Different Smells

New research says our olfactory system is far more sensitive than we thought

:focal(1888x351:1889x352)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/aa/bdaa615a-3dbf-4f93-9a85-1fb1c2248c23/nose.jpg)

You may have heard this one before: Humans, especially compared to animals such as dogs, have a remarkably weak sense of smell. Over and over again, it's reported that we can only distinguish between about 10,000 different scents—a large number, but one that's easily dwarfed by that of dogs, estimated to have a sense of smell that's 1,000 to 10,000 times more sensitive than ours.

It may be indisputable that dogs do have a superior sense of smell, but new research suggests that our own isn't too shabby either. And it turns out that the "10,000 different scents" figure, concocted in the 1920s, was a theoretical estimate, not based on any hard data.

When a group of researchers from the Rockefeller University sought to rigorously figure out for the first time how many scents we can distinguish, they showed the 1920s figure to be a dramatic underestimate. In a study published today in Science, they show that—at least among the 26 participants in their study—the human nose is actually capable of distinguishing between something on the order of a trillion different scents.

"The message here is that we have more sensitivity in our sense of smell than for which we give ourselves credit," Andreas Keller, an olfactory researcher at Rockefeller and lead author of the study, said in a press statement. "We just don't pay attention to it and don't use it in everyday life."

A big part of the reason it took so long to accurately gauge our scent sensitivity is that it's much more difficult to do so than, say, test the range of wavelengths of light the human eye can perceive, or the range of soundwaves the human ear can hear. But the researchers had a hunch that the real number was far greater than 10,000, because it was previously documented that humans have upwards of 400 different smell receptors which work in concert. For comparison, the three light receptors in the human eye allow us to see an estimated 10 million colors.

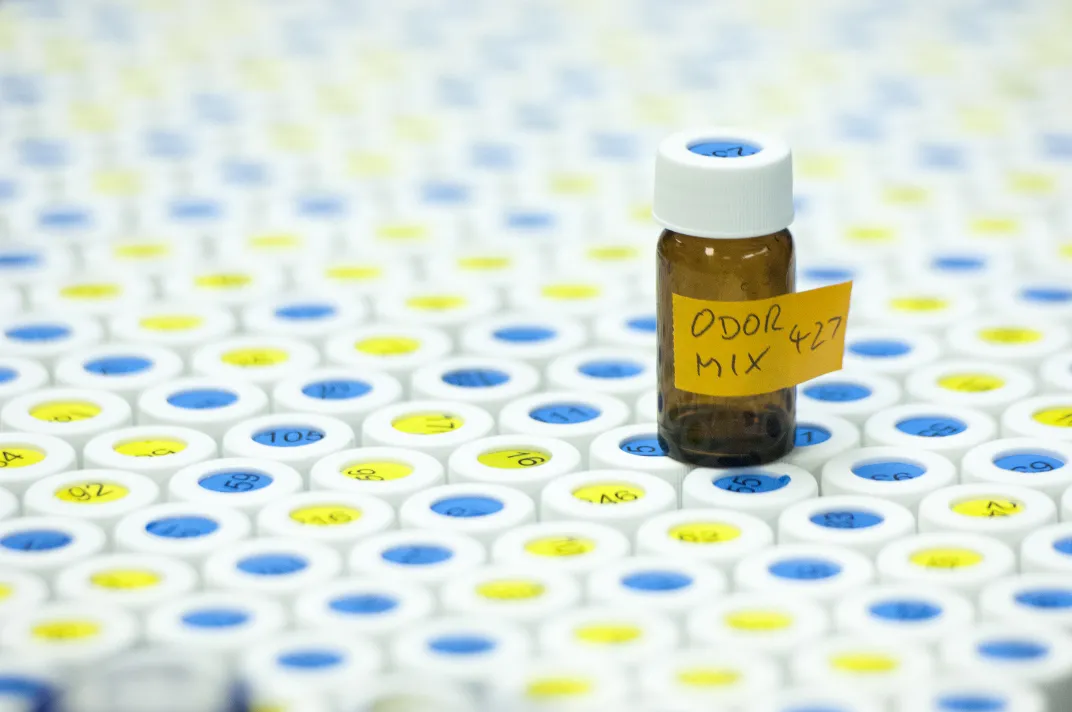

Noting that the vast majority of real-world scents are the result of many molecules mixed together—the smell of a rose, for instance, is the result of 275 unique molecules in combination—the researchers developed a method to test their hunch. They worked with a diverse set of 128 different molecules that act as odorants, mixing them in unique combinations. Although many familiar scents—such as orange, anise and spearmint—are the results of molecules used in the study, the odorants were deliberately mixed to produce unfamiliar smells (combinations that were often, the researchers note, rather "nasty and weird").

By mixing either 10, 20 or 30 different types of molecules together in varying concentrations, the researchers could theoretically produce trillions of different scents to test on the participants. Of course, given the impracticality of asking people to stand around and sniff trillions of small glass tubes, the researchers had to come up with an expedited method.

They did so by using the same principles that political pollsters use when they call a representative sample of voters and use their responses to extrapolate to the general population. In this case, the researchers sought to determine how different two vials had to be—in terms of the percentage of different odorant molecules between them—for participants to generally tell them apart at levels greater than chance.

Then the work began: For each test, a volunteer was given three vials—two with identical substances, and one with a different mixture—and asked to identify the outlier. Each participant was exposed to about 500 different odorant combinations, and in total, a few thousand scents were sniffed.

After analyzing the test subjects' success rates in picking the odd ones out, the authors determined that, on average, two vials had to contain at least 49 percent different odorant molecules for them to be reliably distinguished. To put this in more impressive words, two vials could be 51 percent identical, and the participants were still able to tell them apart.

Extrapolating this to the total amount of combinations possible, merely given the 128 molecules used in the experiment, indicated that the participants were able to distinguish between at least a trillion different scent combinations. The real total is probably much higher, the researchers say, because of the many more molecules that exist in the real world.

For a team of scientists that have devoted their careers to the oft-overlooked power of olfaction, this finding smells like sweet vindication. As co-author Leslie Vosshall put it, "I hope our paper will overturn this terrible reputation that humans have for not being good smellers."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)