Hunters Become Conservationists in the Fight to Protect the Snow Leopard

A pioneering program recruits locals as rangers in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan, where the elusive cat is battling for survival

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/59/ba596ed3-125b-4df2-9e2c-e3f5cee1c054/mar2016_j12_snowleopards.jpg)

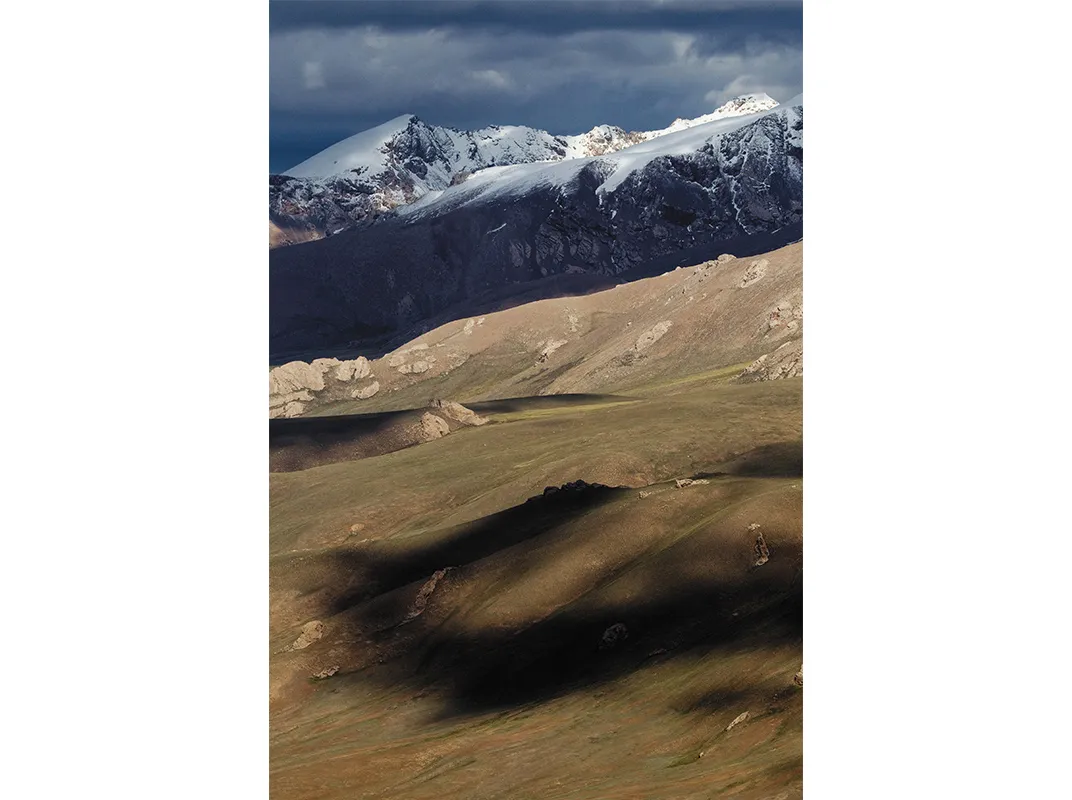

To reach the Tien Shan mountains from the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek, you head east until you hit the shores of a vast freshwater lake called Issyk Kul, and then you turn southeast, in the direction of the Chinese border—a drive of about ten hours, if the weather is good and the roads are clear. The week I made the trip, last winter, in the company of a snow leopard scientist named Tanya Rosen, it took considerably longer. There was rain in Bishkek, and snow on the plains. Every 20 miles or so, we slowed to allow young shepherd boys, stooped like old shepherd men, to drive their sheep from one side of the ice-slick road to the other. In the distance, the mountains loomed.

“Kyrgyz traffic jam,” the driver, Zairbek Kubanychbekov, a Kyrgyz staffer with Panthera, the American nonprofit where Rosen is a senior scientist, called out from behind the wheel. Rosen laughed. “You’ll get used to it,” she told me. “I remember one of the very first things I decided when I came to Central Asia was that I wouldn’t allow myself to get annoyed or angry at the pace of travel here. Because if you do, you won’t have any time for anything else. I surrendered.”

Rosen, who is 42, was born in Italy and raised in what was then Yugoslavia. She speaks six languages fluently, another two passably, and her accent, while vaguely European, can be hard to place. In another life, she worked as a corporate lawyer in Manhattan, but in 2005, frustrated with her job, she and her husband separated and she moved to Grand Teton National Park and then to Yellowstone, to work for the U.S. Geological Survey with grizzly bears while earning a master’s degree in social ecology from Yale. An interest in big-clawed bears gave way to an interest in big-clawed cats, and for the past half decade, Rosen has spent almost all her time studying Panthera uncia, or the snow leopard, an animal whose life in the wild, owing to its far-flung habitat and fundamentally elusive nature, remains little known.

In Tajikistan, Rosen and her colleagues at Panthera helped to set up a network of pioneering community-run conservancies—areas controlled and policed not by government rangers but by local people. The programs were a success—recent surveys showed snow leopard counts inside the Tajik conservancies climbing up. Now she was pushing north, into neighboring Kyrgyzstan, where, except in a single nature reserve called Sarychat-Ertash, little research has been done. So much remains unknown that scientists debate even the size of the snow leopard population itself: Some thought there were a thousand cats in the country, others put the number at 300.

As we hurtled toward the Tien Shan, Rosen ran down the list of what she hoped to accomplish: persuade Kyrgyz hunters and farmers to set up new conservancies; install camera traps to get a rough measure of the snow leopard population in key areas, which could be used as a base line to monitor fluctuations in the years to come; and, if she got lucky, maybe even manage to get a radio collar on an adult snow leopard, allowing her team to track its movements, map its range and learn more about how it interacts with prey and its environment.

Our first destination was a hunting camp high in the Tien Shan, where the owner, a man named Azamat, had reported seeing snow leopards in the surrounding peaks. Azamat had invited Rosen to stay a few days and set up a handful of camera traps. We’d pick up Azamat in his village at the foot of the mountains and continue for another hundred miles up to the camp.

We drove for nine hours straight, past mosques with minarets of sapphire blue, tombs of twisted tin and the occasional dolorous camel. The road narrowed to dirt and reverted back to concrete; we descended only to climb again. I sat in the back seat, next to Naryn, Rosen’s year-old taigan, a Kyrgyz cousin of the Afghan hound. Taigans can be trained to kill wolves, but Naryn, with her gentle, citrine eyes, seemed to have acquired her master’s reserved temperament: She spent her time curled up atop the gear—the better to keep an eye on the rest of us.

Near the shores of Lake Issyk Kul, we stopped to spend the night, and the next day we added another passenger to the already-overstuffed car: Azamat, the owner of the hunting camp. Azamat was dark-haired and absurdly handsome, with little English and a passion for Soviet weaponry; the lock screen on his cellphone, which he showed me immediately after we met, was a glossy photograph of his favorite scoped automatic rifle.

At 12,200 feet, the sage of the plains gave way to the middle reaches of the mountains, and the only other vehicles were trucks from a nearby gold mine. All around us was an ocean of unbroken snowpack; without sunglasses, it hurt to even open your eyes. At 15,000 feet, according to the altimeter on my satellite phone, the air began to feel painfully thin; my vision clouded at the corners with a gray haze, and my head throbbed.

Before I came to Kyrgyzstan, Rodney Jackson, the head of an American nonprofit called the Snow Leopard Conservancy, told me that the reason so few scientists chose to specialize in the feline—as opposed to, say, the tiger—is that tracking snow leopards is an intensely physical endeavor: Altitude hurts, and so does the punishing amount of travel involved. Not everyone wants to spend weeks at a time in the mountains, fending off the nausea and the pain of mountain sickness. I was starting to see what he meant. I swallowed a Diamox pill, a prescription medicine to minimize the effects of altitude, and slumped lower into the bench seat.

Rosen shouted: Ahead, a pack of long-horned argali sheep, a favorite prey of the snow leopard, were watching us approach. But before I could get my binoculars focused, they scattered, flecking the slopes with hoof prints. Four days after leaving home, I’d arrived at last in snow leopard country.

**********

The snow leopard is a deceptively small beast: Males are 95 pounds, give or take, and light through the back and torso. They stand little more than 24 inches tall. (Female snow leopards are smaller still.) And yet as the late naturalist Peter Matthiessen, who wrote his most famous book about the snow leopard, once noted, there are few animals that can match its “terrible beauty,” which he described as “the very stuff of human longing.”

Although snow leopards will descend to altitudes of 2,500 feet, they are most comfortable in steep and rocky mountains of 10,000 feet or higher, in the distant reaches of terrain historically inhospitable to man. It is no accident that in so many cultures, from Buddhist Tibet to the tribal regions of Tajikistan, the snow leopard is viewed as sacred: We must climb upward, in the direction of the heavens, to find it.

And even then, we may not sense its presence. Save for the pink nose and glimmering green or blue eyes, its camouflage is perfect, the black-speckled gray pelt a good blend for both snow and alpine rock. In Kyrgyzstan, I heard stories of experienced hunters coming within yards of a snow leopard without being the wiser for it; the next morning, following the path back to their cabin, the hunters would see tracks shadowing their own.

Although packs of wolves or even a golden eagle may bring down an unprotected cub, the same spring-loaded haunches that allow an adult snow leopard to jump distances of close to 30 feet, from mountain ledge to mountain ledge, make the animal a devastating killer.

Data from the Snow Leopard Trust suggest that the cat will bring down an animal every eight to ten days—ibex or bharal or long-horned argali sheep, whichever large ungulates are nearby—and can spend three or four days picking apart the carcass. Tom McCarthy, executive director of Snow Leopard Programs at Panthera, says he has collared more than a few of the animals in Mongolia with split lips and torn ears: an indication that some of the snow leopard’s prey will fight back. But it’s also possible that male snow leopards “smack each other around,” McCarthy says, in tussles over mountain turf.

Female snow leopards will breed or attempt to breed once every two years, and their home ranges may partially overlap. Pregnancy lasts about 100 days; litters can range from one cub to five, although mortality rates for snow leopard cubs are unknown—the harsh climate, it’s thought, may claim a significant number. Once her cubs are born, a female snow leopard will guard them for a year and a half to two years, until the young leopards are capable of hunting on their own.

The life of a male snow leopard is lonelier. He might stay with a female for a few days while they mate, but after that he’ll typically return to hunting and defending his territory in solitude. In Kyrgyzstan, he is often referred to, with reverence, as “the mountain ghost.”

**********

And yet the snow leopard’s remote habitat is no longer enough to protect it. At one time, thousands of snow leopards populated the peaks of Central Asia, the Himalayan hinterlands of India, Nepal, Mongolia and Russia, and the plateaus of China. Today, the World Wildlife Fund estimates that there are fewer than 6,600 snow leopards in the wild. In some countries, according to the WWF, the numbers have dwindled to the point that a zero count has become a real possibility: between 200 to 420 in Pakistan and 70 to 90 in Russia.

The primary culprit is man. Driven by the collapse of local economies in the wake of the Soviet Union’s dissolution, and enticed by the robust market for snow leopard parts in Asia, where pelts are worth a small fortune and bones and organs are used in traditional medicines, over the past few decades poachers have made increasingly regular forays into the mountains of Central Asia, often emerging with dozens of dead leopards. Cubs are illegally sold to circuses or zoos; WWF China reports that private collectors have paid $20,000 for a healthy specimen. The poachers use untraceable steel traps and rifles; like the leopards themselves, they operate as phantoms.

As the human population expands, the snow leopard’s range has shrunk in proportion—villages and farms crop up on land that once belonged exclusively to wild animals. In Central Asia, a farmer who opens his corral one morning to find a heap of half-eaten sheep carcasses has plenty of incentive to make sure the same snow leopard doesn’t strike again. Meanwhile, snow leopard habitat is being chipped away by mining and logging, and in the future, McCarthy believes, climate change could emerge as a serious threat. “You might end up with a scenario where as more snow melts, the leopards are driven into these small population islands,” he says.

McCarthy points out that the loss of the snow leopard would mean more than the loss of a beautiful creature, or the erasure, as in the case with the Caspian tiger, which vanished in the mid-20th century, of a link to our ecological past. Nature is interlocked and interdependent—one living part relies on the next. Without snow leopards, too many ungulates would mean that mountain meadows and foliage would be chomped down to dirt. The animal’s extinction would forever alter the ecosystem.

In recent years, much of the work of organizations such as the WWF, Panthera and the Snow Leopard Trust has centered more on people than the cats themselves: lobbying local governments to crack down on poaching; finding ways to enhance law enforcement efforts; and working with local farmers to improve the quality and safety of their corrals, because higher fences means fewer snow leopard attacks on livestock and so fewer retaliatory shootings.

“There’s a temptation to think in terms of grand, sweeping solutions,” Rosen told me. “But, as with all conservation, it is less about the animal than it is getting the best out of the human beings who live alongside it.”

Jackson says that the primary challenge is one of political will. “I’m convinced that in places where anti-poaching laws are strict, like Nepal, things have gotten markedly better,” he told me. “People have seen the cultural incentive in having the cat alive. And they’ve watched people get prosecuted for poaching, and they’re wary of messing with that.” But activists and scientists like Jackson have been working in places like Nepal for decades.

By comparison, Kyrgyzstan is a new frontier.

**********

Azamat’s hunting camp turned out to be a cluster of trailers sheltered to the east by a stone cliff and to the west by a row of rounded hills. There was a stable for the horses used by visiting hunters, a gas-powered generator for power and wood stoves for heat. Ulan, a ranger acquaintance of Azamat’s, had arrived earlier in the day with his wife, who would do the cooking.

We ate a wordless meal of bread and soup and threw our sleeping bags on the bunks in the middle trailer. The stove was already lit. I was sore from the drive, jet-lagged, dehydrated from the elevation. Underneath my thermal shirt, my lungs were doing double-duty. I flicked on my headlamp and tried to read, but my attention span had disappeared with the oxygen. Finally, I got dressed and stepped outside.

The night was immense; the constellations looked not distant and unreachable, as they had back on earth, but within arm’s length. By my reckoning, it was 300 miles to the nearest middle-sized town, 120 miles to the nearest medical clinic and 30 miles to the nearest house.

At 5:30 a.m., Askar Davletbakov, a middle-aged Kyrgyz scientist who had accompanied us to the camp, shook me by the shoulders. His small frame was hidden under four layers of synthetic fleece and down. “Time to go,” he said. He had a camera trap in his hand. Rosen had brought along ten of the devices, which are motion-activated: A snow leopard passes by the lens, and snap, a handful of still images are recorded onto a memory card. Later, the camera is collected, and the data is uploaded to a Panthera computer.

We’d hoped to set out on horseback, but the ice in the canyons was too thin—the horses might go crashing through to the river below—so instead we drove out to the canyon mouth and hiked the rest of the way on foot. It was minus 5 degrees Fahrenheit, and colder with the wind. Through the ice on the river I could see sharp black fish darting in the current. Naryn howled; the sound filled the canyon. Resting totemically in the snow up ahead was the skull of an argali sheep torn into pieces by a pack of wolves. The job had not been finished: Clumps of flesh still clung to the spinal column, and one buttery eye remained in its socket.

Nearby, we found the first snow leopard tracks, discernible by the pads and the long tubular line that the tail makes in the snow. A snow leopard’s tail can measure three and a half feet; the cats often wrap themselves in it in the winter, or use it as a balancing tool when traversing icy slopes. I knelt down and traced my finger over the tracks. “Very good sign,” Rosen said. “Looks fresh. Maybe a few hours old.”

Zairbek removed a camera trap from his pack and climbed up a gully to set it. The process was onerous: You need dexterity to flip the requisite switches, but even a few moments without gloves was enough to turn your fingers blue. Three hours after we’d left camp, we’d traveled two miles and set only four traps.

The canyon narrowed to the point where we were forced to walk single file; the ice groaned ominously underfoot. I watched Ulan, a cigarette in hand, testing the ground with his boot. The accident, when it happened, gave me no time to react: Ulan was there, and then he was not. Azamat pushed past me, got his hands under Ulan’s armpits, and hauled him out of the river. The hunter was soaked through to his upper chest; already, his face was noticeably paler. We set the remaining traps as quickly as we could, in caves and in cascades of scree, and turned back home, where Ulan, with a mug of hot tea in hand, could warm his legs in front of the stove.

We ate more soup and more bread, and drank large glasses of Coca-Cola. While in the mountains, Rosen consumes the stuff by the gallon—something about the caffeine and sugar and carbonation, she believes, helps to ward off altitude sickness. I wondered aloud, given the difficulty of just the past couple of days, whether she ever felt overwhelmed. Surely it would be more comfortable to continue to study the grizzly, which at least has the sense to live closer to sea level.

Rosen considered this for a moment, and then she told me a story about a trip to Central Asia a few years back. “I was tired, I was sore,” she said. “We’d been driving all day. And then, from the window, I saw a snow leopard a few hundred yards away, looking back at me. Just the way it moved—the grace, the beauty. I remember being so happy in that moment. I thought, ‘OK, this is why I’m here. And this is why I’m staying.’”

**********

One afternoon, Rosen took me to visit a man named Yakut, who lived in a small village in the Alai Valley, close to the border of Tajikistan. Yakut is slight and balding, with a wispy gray goatee. As a young man in the 1970s, he’d traveled to Russia to serve in the Soviet Army; afterward he had wanted to stay in Moscow and enroll in a university there—there were plenty of opportunities for an ex-military man. But his father forbade it—Yakut was the only boy in the family—and he returned to the village, married and took over the family farm. In the summers, he hunted. He’d killed a lot of animals: ibex, wolves, bears, argali sheep.

In the summer of 2014, Rosen approached Yakut and other hunters in the village to make an offer: Allow Panthera to assist in establishing a local-run conservancy in the Alai. Unlike the National Park Service in the United States, or the zapovednik system in Russia—top-down institutions, where the government designates the protected land and hires rangers to police it—the community-based conservancy model is premised on the belief that locals can often be better stewards of their land than the federal government, especially in fractious areas like Central Asia.

Rosen, with the assurance of local law enforcement and border guards, promised the villagers of the Alai that in addition to helping set up the conservancy, they would assist in negotiations with the government for a hunting parcel, where they could charge visitors a fee to hunt animals like sheep and markhor, a large mountain goat. At the same time, the locals would monitor wildlife populations and carry out anti-poaching work.

Wealthy Kyrgyz city-dwellers and foreign tourists will pay tens of thousands of dollars to bring down an argali sheep. A month earlier, the villagers had registered the conservancy and elected Yakut as its head. Yakut received us at the door to his hut in a watch cap and olive military fatigues—a habit left over from his army days. His home, in the manner of many Kyrgyz dwellings, was divided into three chambers: a hallway for boots and gear; a kitchen; and a shared room for sleeping. We sat cross-legged on the kitchen floor. The television, tuned to a station out of Bishkek, burbled along agreeably in the background.

Yakut’s wife appeared with bread and tea and old plastic soda bottles filled with kumiss, an alcoholic delicacy made from fermented mare’s milk. The first gulp of kumiss came shooting back up my throat; it had the consistency of a raw oyster, and the taste of sour yogurt and vodka. I tried again. It was no better, but this time it went down. Yakut beamed.

I asked him what had made him agree to chair the conservancy, whether there was an appeal besides additional income for the village. “I used to go up into the mountains and see a snow leopard almost every other day,” he said. “Now, months and months can go by before I see a single track. The animals have started to disappear.” He explained that the other week, he and his fellow villagers had stopped a group of young hunters with bolt-action rifles who appeared to be headed onto the land, possibly in search of snow leopards. Perhaps they’d be back, but probably not—it would likely be more trouble than it was worth to attempt another incursion.

“My hope,” Yakut continued, “is that one day, maybe when my grandchildren are grown, the snow leopards will start to return.”

Outside, the sky was low-bellied and dark. Yakut gestured to the wall of his shed, where a wolf carcass hung. He and a cousin had trapped and killed it just the other day. The belly had been slit open and stuffed with hay to preserve the shape. Rosen, noticeably upset, turned away.

As she later told me, building community-based conservancies involved trade-offs: Some animals would be protected, but others would still be hunted. You knew that going in, but it didn’t mean you had to like it.

That night, we slept on the floor of a hut owned by the head of a nearby conservancy. Tossing and turning in my sleeping bag, I listened as Rosen, on the other side of the room, spoke by phone with her 11-year-old daughter, who was living with her father in New York. (Rosen divorced her first husband and has since remarried.) The conversation started in Italian, broke into English, and ended with a series of ciaos and blown kisses. Last year, Rosen’s daughter joined her mother for a few weeks in the field, and Rosen hoped she’d visit Kyrgyzstan again soon. But in the meantime they would be apart for nearly half a year. The separation, she told me, was the single toughest part of her job.

**********

The most successful government conservancy in Kyrgyzstan, alongside Sarychat-Ertash, is Naryn, less than a hundred miles north of the Chinese border. Rangers, despite being paid the equivalent of $40 a month, are well-known for their commitment to the land. A few years ago, the director single-handedly created a museum devoted to indigenous animals, and he has poured the resulting funds (along with proceeds from a nearby red deer farm) directly back into the reserve.

I traveled to Naryn with Rosen, Askar and Zairbek to meet with the Naryn rangers. It had been a month or so since Rosen had been in touch with the team, who had set a series of Panthera-purchased camera traps in the surrounding hills, and she was keen for an update.

Our horses were a few hands taller than ponies but more nimble than the average American thoroughbred, with manes that the rangers had tied up in elaborate braids. Rosen grew up riding—as a teen she’d competed in dressage, and had briefly contemplated a career as a professional equestrian—and she was assigned a tall stallion with a coat that resembled crushed velvet. I was given a somnolent-looking mare.

I locked my left foot in the stirrup and swung myself up over the saddle, which was pommel-less, in the manner of its English counterpart, and set atop a small stack of patterned blankets. The horse shimmied, nosed at the bit, sauntered sideways across the road and was still. Hanging from the saddle was a tasseled crop, which could be used if my heels failed.

We set off in midafternoon, following a narrow track into the hills. The higher we climbed, the deeper the snow became, and at periodic intervals the horses would fall through the top crust with a terrified whinny, pinwheeling their legs for traction. Then their hooves would lock on firm ground and they’d surge forward, in a motion not unlike swimming, and their gaits would once more level out. Soon my mare’s neck and withers were frothed with sweat.

Approaching 10,000 feet, we were suddenly greeted by a flood of horses, saddleless and without bridles, coursing down the opposite slope in our direction. Our mounts grew skittish, and for a moment it looked as if we’d be driven backward off the cliff, but at the last moment a Kyrgyz cowboy appeared from the east, clad in a leather jacket and a traditional peaked Kyrgyz hat, and cut the horses off before they could reach us.

I listened to Zholdoshbek Kyrbashev, the reserve’s deputy director, and Rosen speaking in Russian; Zairbek, riding next to me, translated in his beginner’s English. Zholdoshbek believed there were at least a dozen snow leopards in the reserve—although the photo evidence was scant, the rangers had found plenty of scat. Rosen promised to try to provide the rangers with more cameras. Next they discussed the possibility of trapping and collaring some of the local bears, in order to get a better understanding of their behavior and movements. “It’s a great idea—but you’ll be careful,” Rosen chided him.

Zholdoshbek nodded, and smiled shyly. Like all the Kyrgyz scientists and rangers I met, he clearly liked Rosen immensely, and more than that he seemed to trust her—there was no guile to her, no arrogance. I thought of something that Tom McCarthy, of Panthera, had told me. “You look back to the 1980s, the early 1990s, and you could count the number of people studying the snow leopard on two hands,” he said. Now there were hundreds around the world, and, he went on, “Tanya has become one of the most prominent figures—she’s just absolutely superb at what she does: At the politics of it, at the fieldwork. She’s smart, but she’s always listening.”

The sun was now almost extinguished. We wheeled in a circle along the slope and descended into a valley. In the distance, a scattering of rocks materialized; the rocks became houses; the houses became a village. We dropped in on Beken, a veteran ranger at the reserve. He was a large man, with a face creased by the sun and wind and hands the texture of a catcher’s mitt. As we talked, his 5-year-old daughter climbed into his lap and, giggling, pulled at his ears.

Beken kept talking: He had many plans for the reserve. He wanted Naryn to become an international tourist attraction. He wanted more red deer. He wanted a bigger staff. And above all, he wanted to ensure that the snow leopard would never disappear from this land, which had been the land of his grandfather and father, and would be the land of his daughter.

“The snow leopard,” Beken said, “is part of who we are.”

**********

It took two days to drive back to Bishkek. The highway was full of curiosities: telephone poles topped by storks’ nests; a man with what appeared to be a blunderbuss, taking aim at a scattering of songbirds. After a week in the mountains, the Irish green of the pastures looked impossibly bright, the Mediterranean blue of the Naryn River incandescent.

In Bishkek, with its unlovely Brutalist architecture, a fresh rainstorm arrived; the rain turned to pellets of ice. In the markets, vendors ran for cover. Behind us, shrinking in the Land Cruiser’s side-view mirrors, were the Tien Shan, wreathed in fog.

A few weeks after I returned to the United States, I heard from Rosen, who had sad news: Beken, the ranger at Naryn, had been retrieving a memory card from a camera trap when the river swept him away. His colleagues found him weeks later. He left behind his wife and children, including the young daughter I had watched yank at his ears. It was stark evidence of the dangers, and the cost, of the work Rosen and her colleagues choose to do.

Then, in the fall, came happier news: Working with the Snow Leopard Trust and its local affiliate, the Snow Leopard Foundation, Kyrgyzstan, Rosen and her team at Panthera had set ten snares in the canyons of the Sarychat-Ertash Reserve. “For weeks nothing happened,” Rosen wrote to me. “But on October 26, the transmitter attached to one of the traps went off. At 5 a.m., the team picked up the signal and within one and a half hours reached the site.”

There they found a healthy female snow leopard. The scientists darted the cat and attached a collar fitted with a satellite transceiver. It was the first time a snow leopard had ever been collared in Kyrgyzstan—a development that will shed light on the animal’s habits and range, and its relationship with the local ecosystem. Does the Kyrgyz snow leopard wander more widely than its counterparts in Nepal and elsewhere? Does it hunt as often? How frequently does it come close to human settlements?

Already, Panthera has found that the leopard is a mother to three cubs, who have been captured on camera traps. For now, Rosen and her team are calling the leopard Appak Suyuu, or True Love.

Saving the Ghost of the Mountains