Intriguing Science Art From the University of Wisconsin

From a fish’s dyed nerves to vapor strewn across the planet, images submitted to a contest at the university offer new perspectives of the natural world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Collage-Science-Art-Wisconsin-631.jpg)

“The scientist does not study nature because it is useful; he studies it because he delights in it, and he delights in it because it is beautiful. If nature were not beautiful, it would not be worth knowing, and if nature were not worth knowing, life would not be worth living.”

—Jules Henri Poincare, a French mathematician (1854-1912)

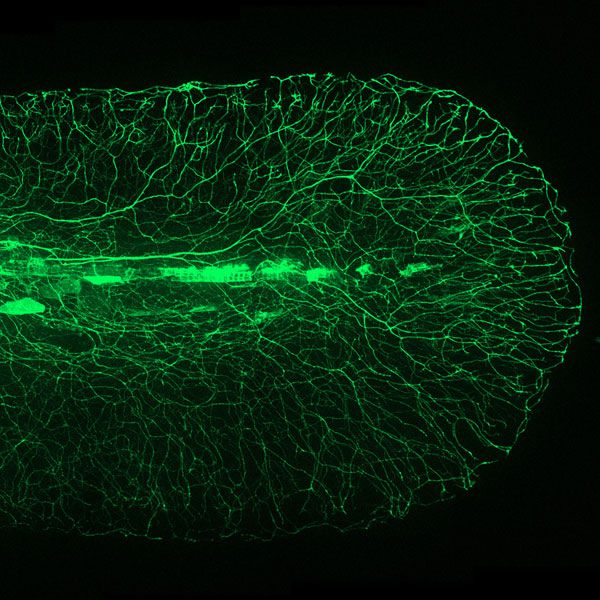

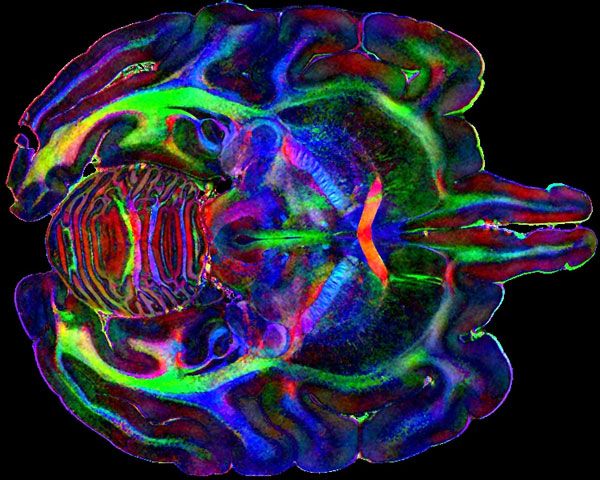

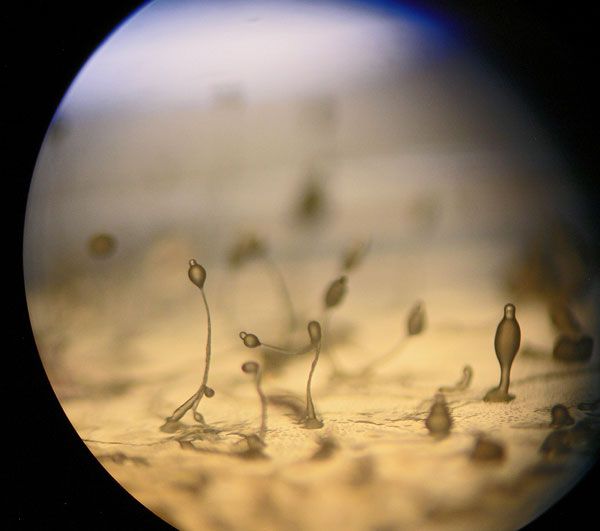

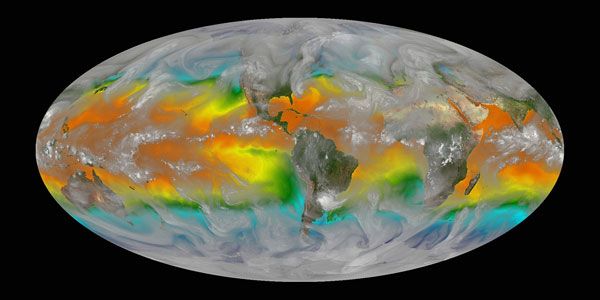

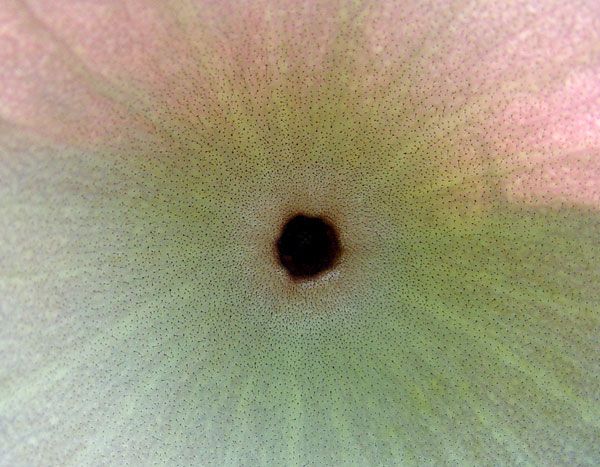

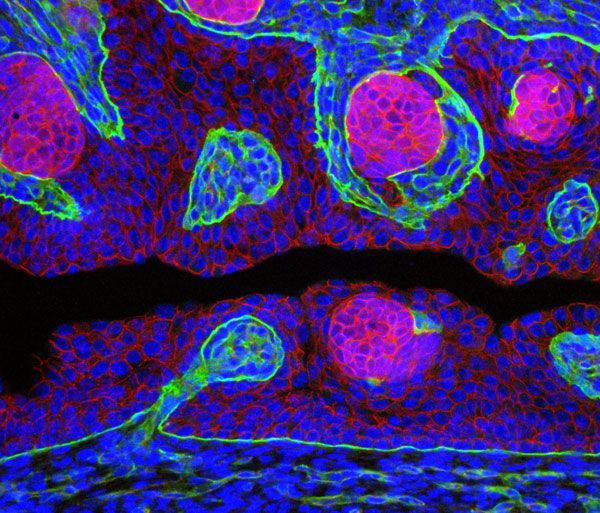

Earlier this month, the University of Wisconsin-Madison announced the winners of its 2013 Cool Science Image contest. From an MRI of a monkey’s brain to the larva of a tropical caterpillar, a micrograph of the nerves in a zebrafish’s tail to another of the hairs on a leaf, this year’s crop is impressive—and one that certainly supports what Collage of Arts and Sciences believes at its very core. That is, that the boundary between art and science is often imperceptible.

The Why Files, a weekly science news publication put out by the university, organizes the contest; it started three years ago as an offshoot of the Why Files’ popular “Cool Science Image” column. The competition rallies faculty, graduate and undergraduate students to submit the beautiful scientific imagery produced in their research.

“The motivation was to provide a venue and greater exposure for some of the artful scientific imagery we encounter,” says Terry Devitt, the coordinator of the contest. “We see a lot of pictures that don’t get much traction beyond their scientific context and thought that was a shame, as the pictures are both beautiful and serve as an effective way to communicate science.”

Most of the time, these images are studied in a clinical context, Devitt explains. But, increasingly, museums, universities and photography contests are sharing them with the public. “There is an ongoing revolution in science imaging and there is the potential to see things that could never before be seen, let alone imaged in great detail,” says Devitt. “It is important that people have access to these pictures to learn more about science.”

This year, the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s scientific community entered 104 photographs, micrographs, illustrations and videos to the Cool Science Image contest—a number that trumps last year’s participation by about 25 percent. The submissions are judged, quite fittingly, by a cross-disciplinary panel of eight scientists and artists. The ten winners receive small prizes (a $100 gift certificate to participating businesses in downtown Madison) and large format prints of their images.

“When I see an image I love, I know the second I see it. I know it because it is beautiful,” says Ahna Skop, a judge and geneticist at the university. She admits she has a bias for images capturing nematode embryos and mitosis, her areas of expertise, but like many people, she also gravitates to images that remind her of something familiar. The scanning electron micrograph, shown at the top of this post, for example, depicts nanoflowers of zinc oxide. As the name “nanoflower” suggests, these chemical compounds form petals and flowers. Audrey Forticaux, a chemistry graduate student at UW-Madison, added artificial color to this black and white micrograph to highlight the rose-like shapes.

Steve Ackerman, an atmospheric scientist at the university and a fellow judge, describes his approach: “I try to note my first response to the work—am I shocked, awed, baffled or annoyed?” He is bothered when he sees meteorological radar images that use the colors red and green to depict data, since they can be difficult for color blind people to read. “I jot down those first impressions and then try to figure out why I reacted that way,” he says.

After considering artistic qualities, and the gut reactions they trigger, the panel considers the technical elements of the entries, along with the science they convey. Skop looks for a certain crispness and clarity in winning images. The science at play within the frame also has to be unique, she says. If it is something that she has seen before, the image probably won’t pass muster.

Skop hails from a family of artists. “My father was a sculptor and my mother a ceramicist and art teacher. All of my brothers and sisters are artists, yet I ended up a scientist,” she says. “I always tell people that genetically I’m an artist. But, there is no difference between the two.”

If anything, Skop adds, the winning entries in the Cool Science Image contest show that “nature is our art museum.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)