Invasion of the Lionfish

Voracious, venomous lionfish are the first exotic species to invade coral reefs. Now divers, fishermen—and cooks—are fighting back

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/lionfish-invasion-631.jpg)

It took as few as three lionfish to start the invasion. Or at least, that's the best guess. Genetic tests show that there weren't many. No one knows how the fish arrived. They might have escaped into Florida's waters in 1992, when Hurricane Andrew capsized many transport boats. Or they might have been imported as an aquarium curiosity and later released.

But soon those lionfish began to breed a dynasty. They laid hundreds of gelatinous eggs that released microscopic lionfish larvae. The larvae drifted on the current. They grew into adults, capable of reproducing every 55 days and during all seasons of the year. The fish, unknown in the Americas 30 years ago, settled on reefs, wrecks and ledges. And that's when scientists, divers and fishermen began to notice.

In 2000, a recreational diver saw two tropical lionfish clinging improbably to the submerged ruins of a tanker off the coast of North Carolina, nearly 140 feet below the surface. She alerted the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, which started tracking lionfish sightings in the Atlantic. Within two years, the fish had been seen in Georgia, Florida, Bermuda and the Bahamas. They are now known to live from Rhode Island to Belize.

"I've never seen any fish colonize so quickly over such a vast geographic range," says Paula Whitfield, a fisheries biologist at NOAA.

Lionfish are the first exotic species to invade coral reefs. They have multiplied at a rate that is almost unheard of in marine history, going from nonexistent to pervasive in just a few short years. Along the way, they've eaten or starved out local fish, disrupted commercial fishing, and threatened the tourism industry. Some experts believe that lionfish are so widespread that their effect on the ecosystems of the Western Atlantic will be almost impossible to reverse. Still, some people are determined to try, if only to protect those waters which haven't yet been invaded.

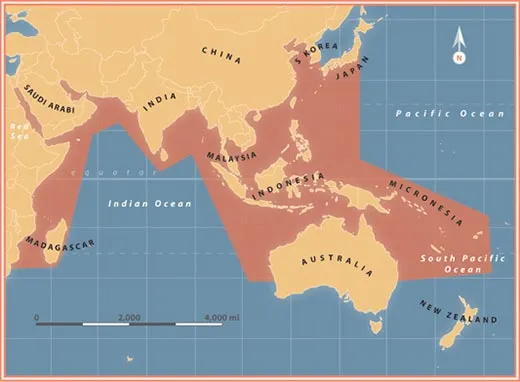

Lionfish are native to the warm tropical waters of the Indian and South Pacific Oceans, nearly 10,000 miles away from the Florida shore. There are many species of lionfish in the world's oceans, and they can be hard to tell apart. All the lionfish identified in the Bahamas have been Pterois volitans, and the species is now common throughout the Western Atlantic, but some closely related Pterois miles have been found as well. Scientists don't know which species was the first to invade, but both invasions started small: genetic tests of the two species in the Atlantic show very little genetic diversity.

Lionfish grow up to a foot long and sport candy cane stripes. Their sharp spines contain a powerful venom. Although a single prick from a lionfish spine can cause days of swelling, discomfort and even paralysis, Americans import thousands of lionfish every year for aquarium use.

Lionfish herd smaller fish into pockets of coral reef or up against barriers and then swallow the prey in a single strike. In their native range, lionfish eat young damselfish, cardinal fish and shrimp, among others. In the Western Atlantic, samples of lionfish stomach contents show that they consume more than 50 different species, including shrimp and juvenile grouper and parrotfish, species that humans also enjoy. A lionfish's stomach can expand up to 30 times its normal size after a meal. Their appetite is what makes lionfish such frightening invaders.

Little is known about what keeps lionfish in check in their home waters. In the Atlantic, adult lionfish have no known predators. Lab studies have shown that many native fish would rather starve than attack a lionfish.

Whitfield, the fisheries biologist at NOAA, began to study the troublesome new invader in 2004. She looked for lionfish in 22 survey sites from Florida to North Carolina. She expected to find lionfish in a few of the sites; instead, she found them in 18. She found lionfish in near-shore waters, coral reefs and deep ocean. At some sites lionfish outnumbered native fish. She estimated in 2006 that there were almost 7 lionfish living in each acre of the western Atlantic. More recent studies suggest that number has grown by 400 percent.

Lionfish are even more common in the warm waters around the Bahamas, where some scientists report finding as many as 160 fish per acre. There are so many lionfish, and in such a variety of habitats, that it might not be possible to completely eradicate the species in this part of the Caribbean. Millions of tourists visit the Caribbean islands each year, many drawn by the chance to snorkel or scuba-dive. The sea is home to more than 1200 species of fish, many of which don't exist anywhere else. "The lionfish could have a devastating effect on business," says Peter Hughes, whose company leads nearly 1000 tourists on guided dive tours in the Caribbean every year.

The local economy depends not just on tourist dollars, but on valuable food fish like grouper, shrimp and lobster. A study released by Oregon State University last year found that in just five weeks, invasive lionfish could reduce the number of young native fish on a reef by almost 80 percent.

On January 6, Lad Akins got the call he had hoped would never come.

For the past several months, Akins has used his position as director of special projects for the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF), a consortium of recreational scuba divers, to fight back against lionfish. He knows how to handle and kill a venomous lionfish, and he's been working with REEF to organize teams of divers who can do the same.

In June 2008, REEF sponsored a two-day lionfish workshop with the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, the United States Geological Survey and NOAA. Local government, state park officials and anyone else who might have a say in southeast Florida's marine management put together a system known as "early detection, rapid response." If volunteers reported a lionfish sighting, officials would immediately notify each other and dispatch a specially trained crew to dispose of the fish.

In January, a vacationing REEF diver reported a lionfish sighting five miles offshore from Key Largo, in the Keys Sanctuary.

It was the first sighting in the Sanctuary, a wildlife refuge that authorities hope to protect from the ecological ravages of invasion. Akins followed the early detection procedure. He examined the diver's photos and verified that she had, in fact, seen a lionfish. He called the superintendent of the Keys Sanctuary and told him that they'd found the first lionfish in Sanctuary waters. Then he called USGS, which has been tracking lionfish sightings since 2002. Finally, he put in a call to a dive shop near Key Largo.

The next morning at 9, Akins boarded a dive boat along with a manager from the Keys Sanctuary, the executive director of REEF, a videographer and a local diver who knew the waters. They moored their boat to a buoy near where the lionfish had appeared. Akins and the others put on scuba gear and slipped beneath the surface.

The diver had reported the seeing the lionfish at Benwood Ledge, a coral shelf that starts 50 feet below the water's surface. It slopes down to about 80 feet deep and then flattens into sand.

In 15 minutes, they found the lionfish. It lazed at the base of the ledge, displaying its striped fins and vicious spines. They shot some footage and took notes on the lionfish's location and habitat. Then they trapped the foot-long fish between two hand nets and brought it aboard the boat. They injected it with a mixture of clove oil and alcohol, which killed it painlessly and almost at once.

They were done by 11:30 in the morning, less than 24 hours after they got the call.

The early detection, rapid response system operated like clockwork, but even Akins says it won't work against the thousands of lionfish already living in the Bahamas, or the ones on the East Coast of the United States. There aren't enough divers in those areas, and it takes time to train personnel to dispose of lionfish.

"We may not be able to remove lionfish from the Bahamas, but if we get an early handle on it, we might be able to prevent the invasion from spreading by removing new fish immediately from new areas," he says.

James Norris, an ecologist working for NOAA in North Carolina, wants to reduce lionfish populations in areas where the species has already established itself. He has been studying small populations of lionfish for the past two years at NOAA test sites off the coast of North Carolina, near where divers first spotted lionfish hanging off the wreck of the old tanker nine years ago.

He uses Chevron traps, 5-foot by 5.5-foot wire cages shaped like arrowheads, at 20 test stations. "I came up with the idea because we got reports that lionfish were going into lobster traps in Bermuda and in the Bahamas," Norris says. The traps captured at least three or four lionfish each, sometimes capturing significantly more lionfish than any other species. Norris says he has to do more research into the issue of "bycatch," the unintended trapping of other species, before divers can start using the Chevron traps in the fight against invasive lionfish.

"When I started I didn't have any idea that lionfish would even go in a trap, so just identifying trapping is a huge accomplishment," Norris says. It will be another two years before Norris refines his trapping technique, but if he does, the traps could be used to capture large numbers of lionfish in areas where scuba divers and spear-fishers don't normally go.

Fishermen in the Bahamas have come up with their own approach to combating lionfish, one that pits man against fish.

In April 2008, nearly 200 people came to the headquarters of the Bahamas National Trust, the organization responsible for managing the country's parks and wildlife sanctuaries, to watch Alexander Maillis cook a lionfish on live local morning television. With his bare hands, Maillis extracted a lionfish from a pile at his side and demonstrated how to slice off the poisonous spines. Local fishermen came up and touched the fish. Later, everyone at the program tasted a slice of pan-fried lionfish.

Maillis works as a lawyer but comes from a family of commercial fishermen. The Maillis family traces its origin to Greece, and this heritage is what first gave Alexander the idea to serve lionfish in the Bahamas.

"Greeks in the Mediterranean have been eating lionfish for years with no ill effects," Maillis says. Lionfish are not native to the Mediterranean, either. Members of Pterois miles, the less common species in the Atlantic invasion, invaded the Mediterranean sometime in the 1980s via the Suez Canal. "And it's a highly prized panfish in the Pacific Rim." Together with a cousin who is also a fisherman, Maillis taught himself how to handle and cook a lionfish. He learned that if he sliced off the venomous dorsal and anal fins, or if he cooked the fish at high temperatures, the lionfish became harmless. Lionfish flesh isn't poisonous, and heat neutralizes the spines' toxins.

Maillis says that his friends were doubtful about his new dish until he cut open a lionfish stomach and showed them the nine baby parrotfish and three small shrimp inside it. Seeing such a vast number of young prey inside a single fish illustrated what a voracious predator the lionfish could be. Now Maillis' friends are on board. One of them got so swept up that when he later spotted a lionfish in the water off the beach, he rigged a spear from an umbrella and a knife, stabbed the lionfish, and cooked the fish for his family.

"We realized that the only way to check the invasion is to get people to start killing lionfish," Maillis says. "If you can find a use for the fish, all the better."

At the request of the Bahamas National Trust, Maillis and other members of his family have led five lionfish-frying workshops on various Bahamian islands. He hopes to make the workshop a regular event all over the Caribbean. And the Trust has campaigned to get restaurants to fry up fresh lionfish for customers.

In the western end of Nassau, the capital city of the Bahamas, the August Moon Restaurant and Café has been serving lionfish since 2007. Alexander Maillis' aunt, Alexandra Maillis Lynch, is the owner and chef. She serves lionfish tempura once every two months, whenever she can convince fishermen to supply it to her. She says she offers anywhere between fifteen and twenty dollars a pound for the exotic specialty, nearly twice as much as she pays for the more common grouper.

Sometimes, she has to eat the lionfish in front of hesitant guests, who need proof that the poison has been neutralized. In spite of visitor nervousness, she always sells out of lionfish, and no one ever complains.

"It's one of the most delicious fish I've ever eaten," says Lynch, who describes the flavor as "delicate." Both Gape and Akins, who have tried the lionfish, agree that it's unexpectedly good. Others have compared the lionfish's texture to that of grouper and hogfish.

Pterois volitans may be the one of the ocean's most voracious predators, but on land, Homo sapiens might have it beat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anika-gupta-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anika-gupta-240.jpg)