Invasion of the Longhorn Beetles

In Worcester, Massachusetts, authorities are battling an invasive insect that is poised to devastate the forests of New England

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Beetles-researchers-in-Worcester-631.jpg)

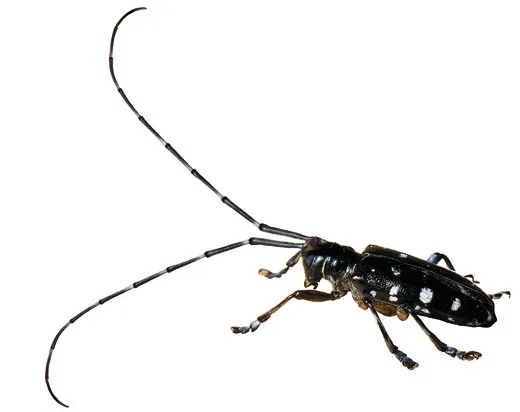

On a pleasant july evening Donna Massie steered her car into her driveway at the bottom of Whitmarsh Avenue in Worcester, Massachusetts. Her husband, Kevin, and his friend Jesse were huddled beside Jesse's car, a gold Hyundai Sonata, and were peering closely at one of its doors. They were staring not at a dent but at a striking black-and-white beetle, about the width of Donna's pinkie and half as long, with bluish legs and two banded antennas that curved back over the length of its body like the whiskers of a catfish.

The beetle gently probed the surface of the car with its forelegs. None of the three was much of a bug person, and Donna was decidedly anti-bug, stipulating a death-to-insect policy in her house. Still, the beetle transfixed her. It was larger than any she'd ever encountered, and with its otherworldly colors it was almost beautiful. Before the creature whirled its wings and flew away, Massie and her husband decided that it must be a June bug, albeit a freakish sort.

The insect might have escaped further notice, and evaded authorities altogether, if the Massies had not hosted a cookout two days later in their backyard, where others began to notice the curious beetles. They were hard to miss, creeping along the trunks of the maple trees that fringed the Massies' yard. Their black wing casings stood out starkly against the silver bark. One beetle planted itself on Kevin's pant leg and had to be pried loose. Then Donna noticed something unnerving. Near the base of one maple, she found a beetle sprinkled with sawdust, its head submerged in a dime-size hole in the tree's trunk. It seemed to be eating its way inward.

The following morning, Donna searched the Internet and identified her backyard visitor as an Asian longhorned beetle, also known by the abbreviation ALB. Her search also turned up a pest alert from the state of Florida that warned of the dangers posed by the insect. Donna began leaving messages with various agricultural authorities.

Patty Douglass, who works for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), was in her office in Wallingford, Connecticut, 75 miles south of Worcester, when Donna Massie's call came through. In her position as the plant health director for Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, Douglass regularly fields phone calls from gardeners, landscapers and amateur entomologists who believe they've encountered one of the nonnative insects on the USDA's threat list. Nearly all of these calls prove to be in error, as the insect universe is almost incomprehensibly large and varied, and mistakes in identification are easily made. The beetle order alone contains some 350,000 known species; by comparison, the total number of bird species is roughly 10,000.

Massie took a photograph of the beetle with her cellphone and sent it in. The portrait was pixelated, but the beetle's speckled black-and-white abdomen and its telltale antennas were unmistakable. Within 24 hours of receiving the image, Douglass and Jennifer Forman Orth, an invasive species ecologist with the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, were standing beside Massie in her backyard, staring up at her trees. Douglass spotted one of the insects, confirming with her own eyes a scenario that she and others at the USDA had long feared—an ALB outbreak in New England. She grabbed Massie's arm. "Oh, God," she said. "They're really here."

For most of its history, the Asian longhorned beetle occupied a small, largely unremarkable niche in the forests of China, Korea and Japan. It was not known as a serious pest. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, the Chinese government began to plant enormous windbreaks of millions of trees in its northern provinces in response to erosion and deforestation. These windbreaks were composed almost entirely of poplar trees, which mature quickly and tolerate the arid, cold climate of northern China. As it happens, the poplar is a tree favored by the ALB, along with maple, birch, elm and several other hardwoods. The beetle is unique among invasive forest pests for attacking such a broad array of hosts, which is partly why it is so dangerous.

Adult beetles feed on leaves, twigs and young bark. Females deposit anywhere from 35 to 90 eggs, one at a time, in pits they dig in the bark. When the eggs hatch, ALB larvae bore into the cambium, the tissue that ferries the tree's nutrients, and then they move into the heartwood. Over several years, this tunneling chokes off a tree's supply of nutrients and kills it—a death by a thousand cuts.

In the 1980s, as China's poplar forests matured, the ALB population exploded. Within a few years, hundreds of millions of trees were infested, and the Chinese government had to cut tens of thousands of acres of forest to prevent the beetle's further trespass.

Meanwhile, China, along with the rest of the world, experienced a surge in foreign trade. Since 1970, global sea trade has tripled, and today more than 90 percent of the world's goods travel at least one leg of their journey by ship. The United States went from importing 8 million sea containers in 1980 to more than 30 million in 2000. And most of those products—diapers, televisions, umbrellas—are packed in crates or on pallets made of wood. In the 1980s, pallets of infested poplar began to leave Chinese ports, carrying Asian longhorned beetle larvae. A stowaway on the global shipping network, the insect came into nearly instant contact with warehouses across the world.

In August 1996, Ingram Carner, a landlord in Brooklyn, New York, noticed that the Norway maples on his property were full of strange perforations, each slightly thicker than a pencil and so perfectly spherical they looked as if they'd been drilled. When the culprit was identified, and the USDA realized the nature of the threat—a beetle with the capacity to destroy numerous native hardwoods—the agency began cutting down thousands of infested trees and chipping them. That's the best way to ensure the beetle's demise; insecticides don't reach it once it has burrowed past the cambium, although they might protect unafflicted trees. In addition, the USDA established a quarantine around much of New York City, prohibiting anyone from transporting wood that could host the beetle. The restriction is still in place. In the 13 years since the initial outbreak, authorities have documented the ALB in Queens, Staten Island, northern New Jersey and on Long Island. The work of eradicating the beetle from the New York City area continues.

Infestations have also been discovered in Chicago and Toronto. The beetles have been intercepted in dozens of ports and warehouses across the country, from Mobile, Alabama, to Bellingham, Washington. But the discovery of an ALB outbreak in Worcester marked an ominous turn. While previous infestations were confined to urban areas with relatively thin tree cover, Worcester—a city of 175,000 people 40 miles west of Boston—is full of trees, most of them hardwoods. More troubling, the city sits at the southern edge of the great Northern hardwood forest, millions of contiguous acres stretching to Canada and the Great Lakes. If the beetle escaped into such a forest, it could prove the most devastating arboreal pest we've ever known, occasioning more damage than Dutch elm disease, gypsy moths and chestnut blight combined. It could change the face of the New England woods.

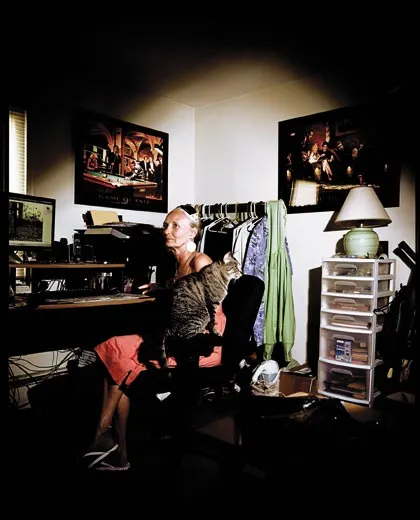

In the bowels of the Massachusetts National Guard Armory in Worcester, in a cramped conference room that serves as a makeshift headquarters, Clint McFarland is staring at a four-foot-wide city map tacked to the wall. The words "Regulated Area" are printed on it. McFarland traces the map with his fingers and reads the names of streets into a cellphone, which is never far from his hands and beeps and barks at him all day long. The room is covered with maps, each articulating a different set of beetle data. Along with the phones that are ringing constantly and the stream of uniformed personnel in and out of the room, the maps lend the impression of a command post hastily assembled on a battlefield.

McFarland, 34, wears his hair in a ponytail, giving him a look that seems slightly at odds with the gold badge emblazoned on his jacket identifying him as an agricultural enforcement officer for the federal government. He has worked for the Animal and Plant Inspection Service (APHIS), the USDA division that deals with agricultural pests, for eight years, all of that time on the Asian longhorned beetle. In October 2008, his supervisors handed him the Worcester assignment. When I first met with him, he had been on the job a little over a month and even then showed signs of exhaustion, with red-rimmed eyes and a rasp in his voice. Stopping the beetle in Worcester was proving more difficult than he or anyone else had first imagined.

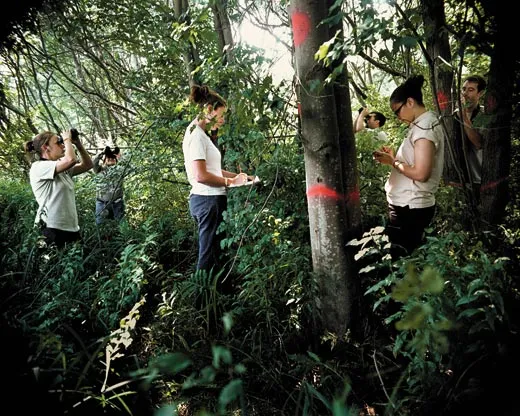

Within days of Donna Massie's telephone call, authorities from APHIS arrived in Worcester to orchestrate a containment plan with state and local officials. A state order was issued forbidding the transportation of all wood from host tree species and all firewood out of a 17-square-mile area in the heart of the city. APHIS assembled several ground survey teams to seek evidence of the beetle: exit holes, egg deposits, sawdust, and sap leaking from wounded trees. The service wanted to understand how wide the infestation was, and how serious. What they found alarmed them.

The life cycle of the ALB is roughly a year, nine months of which is spent buried in wood. While adult beetles are serviceable fliers, they tend not to move very fast. Beetles will often inhabit one tree for many generations until it is nearly dead. A quick way to gauge the length of an infestation is to look at the trees themselves: the more holes they have, the longer the beetles have been around. On street after street in Worcester, survey teams found trees riddled with holes, as if they'd been fired upon with a shotgun. In some cases, the trees were so weakened they'd begun to lose their limbs—victims of a long and sustained attack. It soon became clear that the beetle had found its way to the city a decade ago or longer.

On the day I caught up with him, McFarland was organizing the deployment of more than 20 U.S. Forest Service smoke jumpers, forest firefighters from Western states, who had been brought in to climb through Worcester's trees to search for signs of infestation. Because the beetle first attacks a tree's crown, spotters on the ground may have difficulty detecting the insect; even the smoke jumpers, swinging from ropes and clambering over limbs, manage to identify only about 70 percent of infected trees. Complicating matters for McFarland, the quarantine had been expanded to 62 square miles, and this area encompassed more than 600,000 ALB-susceptible trees, each of which had to be inspected. Ten thousand trees had so far been examined, and more than a third showed evidence of beetles and would have to be destroyed before the summer, when the larvae would transform into voracious flying insects. Worcester was the worst ALB infestation the country had seen.

After McFarland dispatched the smoke jumpers, he drove me to the site of the oldest infestation, located in a stretch of industrial land bordered by a highway on the west and a residential neighborhood on the east. We were accompanied by Ken Gooch of the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. It was a bitterly cold day, one of the coldest on record in November in that part of the state, and the men tramped through the underbrush with their shoulders raised against the wind and their hands thrust in their jacket pockets. McFarland took occasional furious puffs on a cigarette. We walked 50 yards and then Gooch stopped suddenly and pointed at a tree stump. The exposed wood was raw, a pinkish yellow.

"When did that come down?" asked McFarland, raising his voice above the rush of passing highway traffic.

Gooch shook his head. "I don't know."

The men walked around the stump. McFarland stared down at some sawdust and let out a sigh, as if to say, "What next?" The now missing tree had been identified as infested, as had almost all the maples in that part of town. But the cutting and chipping work was not supposed to have begun; whoever had removed the tree was not working for APHIS. The wood was, in effect, a ticking time bomb. Contaminated with beetle larvae, it could become a source for yet another outbreak elsewhere.

Standing beside the two men as they considered the whereabouts of a single tree in a city of trees, I began to grasp the immense challenge of trying to stop an insect from having its way in the world. I thought about all the years the beetle had been in Worcester before it was discovered, years in which wood was moved freely out of the city, in the back of a landscaper's truck, perhaps, or as firewood to be stacked beside someone's cabin in the forests of New Hampshire or Vermont or Maine. I remembered something I had read about the beetle: Chinese farmers, who had watched the insect march across the northern provinces, referred to it as the "forest fire without smoke."

It is no surprise that the beetle's escape from China came via trade. Invasive species have traveled undetected in the ballast of ships, in nursery plants, in crates of fruit, in old tires, even in the wheel wells of airplanes. Life likes to travel, and in the era of globalization it travels at a pace never before known, covering distances never before possible. Thousands of introduced species now prey upon or outcompete native species in the United States. The costs of this ecological upheaval, even in purely economic terms, is staggering—a 2005 Cornell University study put the damage from invasive species at $120 billion per year in the United States alone.

Not long after the Brooklyn infestation was discovered in 1996, the USDA began requiring that solid-wood packing material—the stuff used for shipping crates and pallets—be fumigated or heat-treated to kill the larvae of forest pests. These regulations were applied first in 1998 to Chinese imports and then in 2005 to those from all other nations. The regulations have reduced the entry of the ALB into the country, although, even today, dozens of the beetles are intercepted annually in ports nationwide, and other avenues of entry, such as live plant imports, remain. The protocols established by the government after the Brooklyn outbreak—quarantines, inspections and the destruction of infested trees—have largely succeeded, in part because the beetles disperse slowly on their own.

We have no choice but to fight the insect. The costs of not doing so are enormous—one USDA study puts the potential ALB damage in the United States at more than $650 billion, and that's accounting only for trees in municipalities, not on forested lands. The federal government has spent in excess of $250 million on ALB eradication efforts thus far, and more than $24 million in Worcester. Each known outbreak—in New York, New Jersey, Chicago and Worcester—was discovered in a densely populated area, by an alert citizen, after years of infestation. But what if other infestations are taking place out of sight—near a warehouse in a small town in New Hampshire, perhaps, or behind a lumberyard in upstate New York?

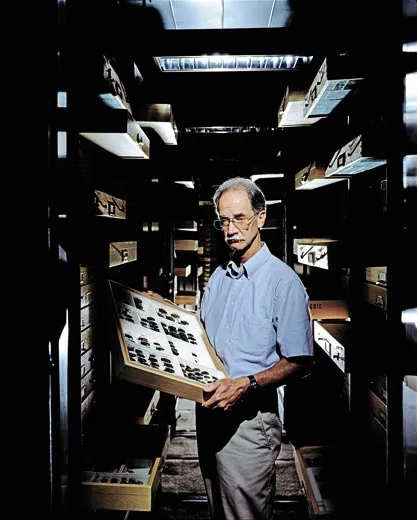

I asked E. Richard Hoebeke, a Cornell University entomologist who has studied the Asian longhorned beetle as long as anyone in the United States, about possible undetected infestations. He talked about the many years the beetle had been invading before it came to our attention. He spoke of the overwhelming number of shipping containers pouring into the country.

"Are there other infestations?" he said. "I'm certain of it. Worcester won't be the last."

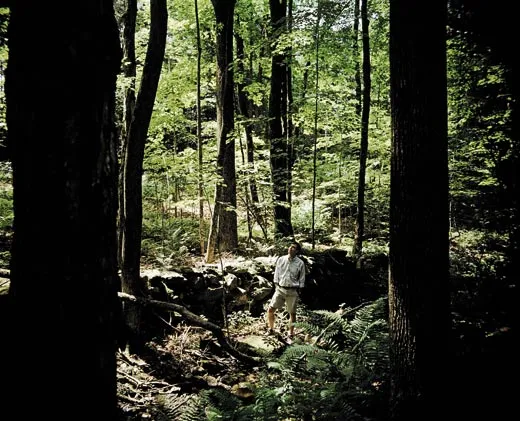

Concerned that the beetle might find its way into the Northern hardwoods, I visited the ecologist David Foster, director of the Harvard Forest, a 3,000-acre parcel in central Massachusetts that is the site of long-term ecological research. How might the beetle change the New England landscape? To ask that question, as it turns out, is to invite others—questions about what shaped the land in the first place. By way of explanation, Foster took me into the woods.

Much of the Harvard Forest, like more than half of New England, was cleared by farmers in the 18th and 19th centuries and later abandoned. Not far into our walk we passed a crumbling stone wall that cut a straight line through the woods. It was nearing dusk, and a skin of ice covered the snow. Foster, a tall man with dark hair and the ruddy complexion of someone who spends a lot of time outdoors, took big, crunching steps along the trail. We passed a stand of pines and ducked under some fallen snags, and then we came to level land populated by maples and birch. "Beetle food," said Foster, wryly.

It would seem to be our poor luck that so much of New England contains habitat so well suited to the ALB, but, as Foster pointed out, that is at least in part of our own making. In the mid-19th century, New England's settlers began to abandon their farms—lured by cities and by the opening of the West—and their fields returned to forest. Trees such as birch and maple and pine spread first and farthest, on land that once hosted more hemlock, beech and oak, which are not susceptible to the beetle. "Most people walk through these woods and don't see the human impact," Foster said. "But if we compare the vegetation of these forests in 1600 with the vegetation of today, we see huge changes. There's a tremendous increase in species like red maple, which is favored by the beetle."

We have shaped the forest in other ways, too. Chestnut trees once accounted for perhaps a quarter of the Eastern forest. But they were wiped out by the 1950s by an Asian fungus brought here on Japanese nursery stock. A shipment of logs from Europe in 1931 introduced Dutch elm disease, another fungal blight, which infected elms across the Northeast. The European gypsy moth, let loose in Massachusetts in the 1860s, has ravaged oaks and other trees, and the hemlock woolly adelgid, an Asian insect introduced to the East Coast in 1951, has caused widespread mortality in hemlocks. Another invasive Asian beetle, the emerald ash borer, is destroying millions of ash trees in the Midwest and Middle Atlantic. The cumulative effect of these and other pests and pathogens is a more homogenous forest, and one that is more vulnerable to invasion. "We're setting ourselves up for more catastrophe," Foster said.

Forests are becoming even more fragile as the climate warms and the range of native forest pests expands. In the Rocky Mountains, hundreds of thousands of acres of aspen have begun to succumb to the combined pressures of drought, disease, warmer weather and insect predation—a phenomenon termed "sudden aspen decline." Pine trees there are dying in even greater numbers: mountain pine beetles, aided by drought and mild winters, are laying waste to millions of acres.

As the evening grew dark, Foster and I turned back toward his office. We stopped at the edge of the forest, and we could see barns and a snow-covered field and the distant lights of a farmhouse. From where we stood, the Worcester outbreak was less than 40 miles away. I wondered what the beetle might do were it to make it here to the Harvard Forest, which harbors some of the oldest woods in all of Massachusetts.

"Even if it comes through here," Foster said, "there'll still be a forest. It may not be the same, but the forest will continue." He kicked at the snow with the toe of one boot and looked out over the field. "It is such a generalist, though," he said of the beetle. "It likes so many trees. I don't know. It really is one of the worst nightmares."

On the night of december 11, 2008, a freezing rain fell over Worcester, and in the hours before dawn Clint McFarland woke several times to the patter of sleet against his window. In the morning, when he stepped outside, he hardly recognized the city. Under a burden of ice, trees had fallen haphazardly onto cars and houses. Limbs littered the streets; nearly half the roads in Donna Massie's neighborhood were impassable. The ice storm, the worst in a decade, had blanketed much of the Northeast, leaving nearly a million homes and businesses without power, injecting an unforeseeable element of chaos into an already complicated beetle eradication effort.

Contractors up and down the East Coast, from as far south as Florida, began arriving in the city in pursuit of debris-removal work, many of them unaware of the ordinance against removing wood from a quarantined area. In the days after the storm, several trucks were seen carting tree limbs away, despite patrols by environmental police. "We know that wood has been moved out of the city," McFarland told me when I caught up with him the following week. "That's our paramount concern right now. It can't happen again."

Driving to a meeting of town officials, McFarland looked beleaguered. He'd been working nearly nonstop for days, and weighing upon him was the thought that he would have to tell his wife he was going to miss Christmas. The ice storm, meanwhile, had pushed back plans to begin cutting and chipping trees, and the tally of infested trees in the quarantine area had risen to nearly 6,000.

We passed streets lined with shoulder-high stacks of branches. On one block, nearly every tree along the road had been marked for ALB-related removal with an ominous red splotch. I asked McFarland if he thought much about what would happen if he failed in Worcester. He laughed and admitted that he did. "But it's in my nature. I have a fear of failure." He smiled. "Look, we can do this. I've been studying this beetle for years and I think eradication is really possible, and that's hard to say about most insects. And we don't have a choice, do we? There is so much at stake. If it hits the Northeastern hardwood forest, you're looking at the maple industry, timber, tourism. It's huge. We really can't fail."

A year later, there is reason for some optimism. The government's containment efforts have so far succeeded. More than 25,000 trees were felled within Worcester city limits in 2009. The area of quarantine around the city has expanded slightly, from 62 to 66 square miles. No new ALB infestations have been discovered outside the city center.

At the height of the crisis in the winter of 2008-2009, log loaders and bucket trucks were arriving by the hour from out of state, and chain saw crews were removing wood from backyards and rooftops and utility lines. Given the concentration of human effort marshaled against a single insect, it was tempting to think that this was the only battle against an invasive species. Yet in California, Virginia, Michigan and Florida—to name just a few affected states—the same drama was unfolding, if with different characters: the emerald ash borer and the hemlock woolly adelgid, sudden oak death and the citrus canker. Beyond our borders, more organisms are poised to invade. On average, we bring a major new agricultural pest into the country every three or four years. Cornell's Hoebeke told me that perhaps as many as 600 of the world's high-risk insect pests were not yet established in the United States, any one of which might prove as virulent as the ALB. He was particularly concerned about the Asian citrus longhorned beetle, which could devastate the country's citrus and apple orchards.

Sitting with McFarland in a car in Worcester listening to the thrum of logging activity, I was struck by what a strange confluence of events had brought the beetle to Worcester, an ocean away from its native range. People are largely to blame, of course. But there seemed an accidental ingenuity in the way the beetle had hitched itself, undetected, to the one species capable of taking it everywhere. I asked McFarland if he ever found something to admire in the Asian longhorned beetle, despite all the trouble it had caused.

"Oh, yes," he said. "I admire all insects. People say that insects will inherit the earth, but entomologists know better. The earth already belongs to the insects. They were here long before us and they've taken over every niche. They're in nearly every inch of soil, and they're in the atmosphere. We wouldn't be here without them—without pollination and decomposition. The earth is theirs. We're just trying to share it for a while."

Peter Alsop writes about science and the environment. Max Aguilera-Hellweg was the photographer for "Diamonds on Demand" in the June 2008 issue of Smithsonian.