Is Your Vote Affected By Your Home Team’s Wins and Losses?

A new study indicates that having a winning sports team may make us more likely to reelect an incumbent politician

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120921094046voting-booths-small.jpg)

It’s football season. It’s election season. Right now, the attention of the American public is focused on a pair of arenas that, superficially at least, have nothing to do with each other.

Political scientist Michael K. Miller of Australian National University (who recently got his Ph.D. from Princeton), though, saw these two realms as a way for him to test a counter-intuitive hypothesis he’s long had in mind: Does your overall level of happiness due to factors as irrelevant as a winning team make you more likely to vote for an incumbent politician? His statistical analysis, published earlier this week in Social Science Quarterly, indicates that the answer is “yes.”

He conducted his analysis to contest a conventional belief in political science. It’s well known that voters tend to reelect incumbent presidents if the economy is thriving and vote for incumbent school board members if test scores go up—in other words, voters opt for the status quo when things are going well. Most political scientists attribute this to voters’ explicitly attributing positive outcomes to incumbent performance, and rewarding them for it with reelection.

Miller, however, wanted to test an alternate idea. “In what I term the ‘Prosperity Model,’ voters simply opt for the status quo when they feel happy,” he writes in the study. “The Prosperity Model holds that voters may favor the incumbent for personal reasons entirely unconnected to politics—say, they just got engaged, it’s a sunny election day or their local sports team just won a big game.”

To distinguish between the conventional model and his alternate idea, Miller needed to examine voter behavior after an event that increased general happiness but had nothing to do with politics. Although the romantic lives of voters and the weather outside polling places might be difficult to track, he saw that comparing local sports’ teams records with incumbents’ success rates was entirely feasible.

To do so, Miller compared incumbent mayors’ success rates in getting reelected with the performances of local football, basketball and baseball teams for 39 different cities for the years 1948 to 2009. He found that when the overall winning percentage of a city’s pro sports teams over the previous year increased by 10 percent, the incumbent’s share of total votes increased by 1.3 to 3.7 percent.

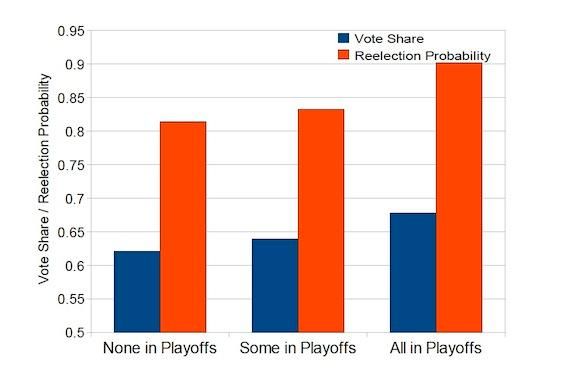

Even more surprising was the effect of teams making the playoffs: When comparing incumbent mayors of cities with no teams making the playoffs to those of cities where all teams made the playoffs, the analysis found that the playoff mayors’ chances of reelection was roughly 9 percent higher. Overall, the statistical impact of the home teams’ winning percentage was greater than that of the politically all-important metric of unemployment.

Although this only proves a correlation, not a causation, it’s a fairly compelling once—especially because Miller tested a hypothetical placebo. If both winning sports teams and reelected incumbents were influenced by a third, unseen factor, then the teams records after the election would also be positively correlated with the incumbents’ success rates. His analysis, though, showed that this wasn’t the case. Only winning records before the elections were tied to incumbents winning more often at the polls, indicating that the relationship might indeed be causative.

Why on earth would voters be so foolish as to vote for the incumbent just because their favorite team won? It may not be a conscious decision. Research shows that our mood affects all sorts of evaluations that we make. Psychologists have shown that a positive mood makes us think favorability about whatever is on our mind—whether it has anything to do with the cause of that happiness or not—and increases our tendency to support the status quo.

Miller’s results, moreover, shouldn’t be entirely surprising: Previous studies, he notes, have shown that a win by the German national soccer team leads to voters seeing the ruling political party as more popular, and that losses by national soccer teams and pro football teams tend to be followed by stock market declines and surges in domestic violence, respectively. This study goes one step further in that it identifies the link between sports success and decision making on a city-specific level.

Despite the seemingly bleak implication of the study—voters are informed by factors as irrelevant as pro sports—Miller doesn’t find it particularly troubling. This seemingly irrational trend, he says, only applies to a small handful of voters; additionally, it simply gives incentive to incumbents to try to make their constituents as happy as possible at election time, hardly a dire problem. Voters can be occasionally imperfect, he says, without undermining the entire value of a democracy.

For politicians, then, what’s the lesson? During campaign season, get to the stadium and root for the home team.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)